Douglas Flora, Executive Medical Director of Yung Family Cancer Center at St. Elizabeth Healthcare, President-Elect of the Association of Cancer Care Centers, and Editor in Chief of AI in Precision Oncology, shared a post on

Category: 6. Health

-

‘Junk’ DNA Could Hide Switches That Allow Alzheimer’s to Take Hold : ScienceAlert

‘Switches’ in our DNA that affect gene activity in cells could be crucial to understanding and possibly treating Alzheimer’s disease, with researchers identifying more than 150 control signals in specialized brain cells called…

Continue Reading

-

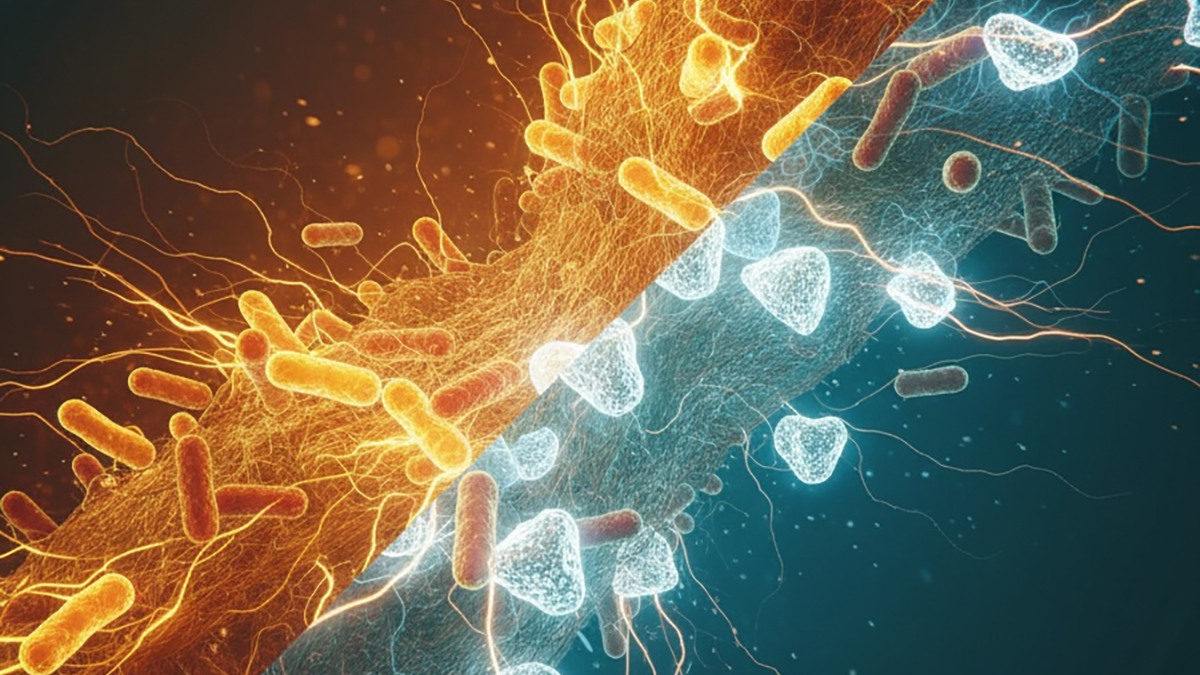

Why some bacteria survive antibiotics and how to stop them

New study reveals that bacteria can survive antibiotic treatment through two fundamentally different “shutdown modes,” not just the classic idea of dormancy. The researchers show that some cells enter a regulated, protective growth…

Continue Reading

-

Individual and institutional factors influencing dentists’ practice in underserved areas

Health, R. & Services AdministrationOral Health Workforce Projections, 2017–2030: Dentists and Dental Hygienists.

Continue Reading

-

Why nail-biting, procrastination and other self-sabotaging behaviors are rooted in survival instincts

Self-harming and self-sabotaging behaviors, from skin picking to ghosting people, all stem from evolutionary survival mechanisms, according to a compelling new psychological analysis.

Clinical psychologist Dr. Charlie…

Continue Reading

-

Ancient genomes reveal Iron Age origins of human herpesvirus 6

For the first time, scientists have reconstructed ancient genomes of Human betaherpesvirus 6A and 6B (HHV-6A/B) from archaeological human remains more than two millennia old. The study, led by the University of Vienna and University…

Continue Reading

-

Weaker and fragmented circadian rhythms linked to higher dementia risk

Circadian rhythms that are weaker and more fragmented are linked to an increased risk of dementia, according to a new study published on December 29, 2025, in Neurology®, the medical journal of the American Academy of Neurology.…

Continue Reading

-

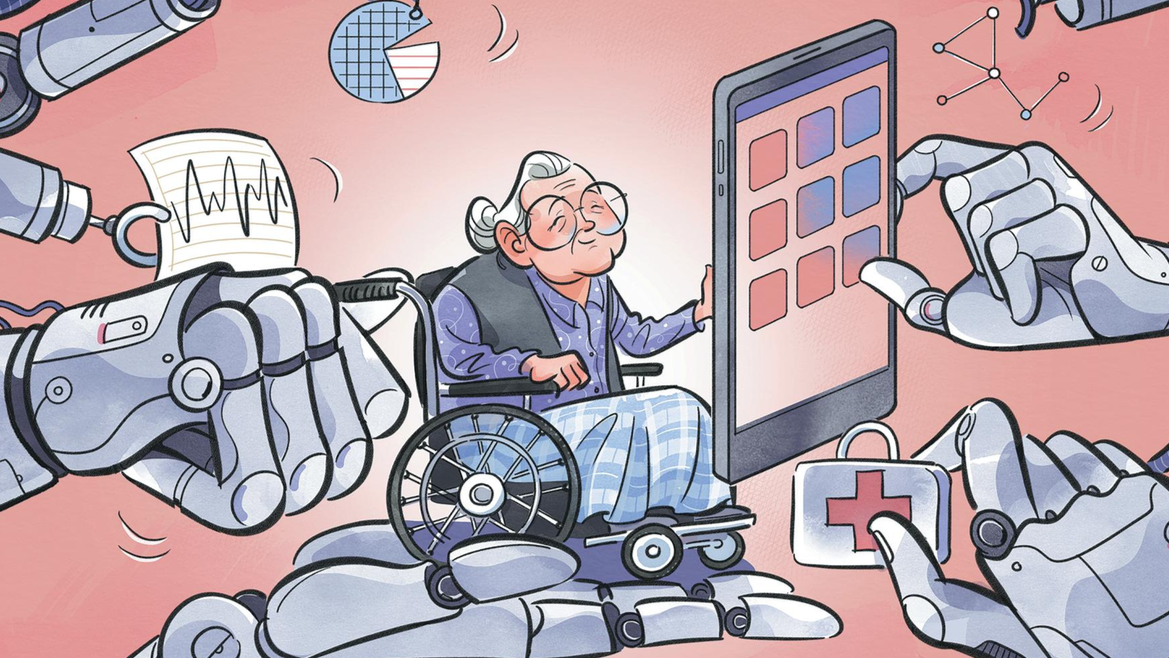

AI has finger on pulse of healthcare advances

(SONG CHEN / CHINA DAILY) Song Jiayi, a 32-year-old white-collar worker in Beijing, usually goes to the gym after work. She likes running on a treadmill for more than an hour and attending various fitness classes with a focus on personal health…

Continue Reading

-

Silencing Bacterial ‘Chatter’ in Your Mouth May Help Prevent Tooth Decay : ScienceAlert

New research shows that ‘hacking’ the communication channels between microbes in the mouth could boost levels of beneficial bacteria – a strategy that could potentially reduce the risk of tooth decay and improve oral hygiene.

Bacteria use a…

Continue Reading