By Matthew Stenger

Posted: 1/2/2026 10:17:00 AM

Last Updated:

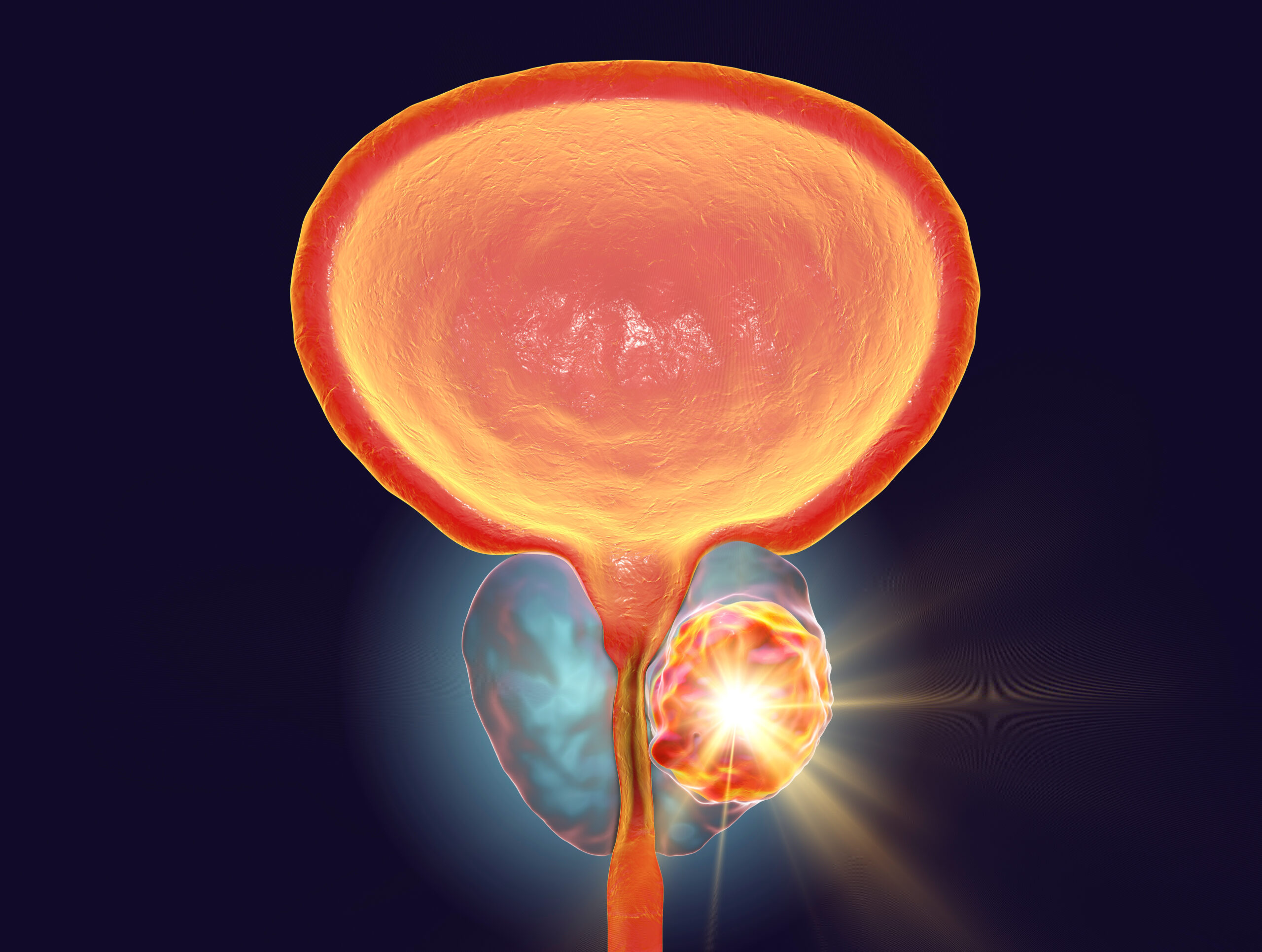

In a meta-analysis reported in JAMA Oncology, Zaorsky et al found that longer durations of androgen-deprivation therapy given with…

By Matthew Stenger

Posted: 1/2/2026 10:17:00 AM

Last Updated:

In a meta-analysis reported in JAMA Oncology, Zaorsky et al found that longer durations of androgen-deprivation therapy given with…

Babies who don’t get their first round of vaccines on time at 2 months of age are much less likely to get vaccinated against measles, mumps, and rubella by age 2, according to a new study that suggests pediatricians may have a narrow window in…

To most, holding a title like “The Father of Geriatric Oncology” might be daunting. However, Lodovico Balducci, MD, humbly accepts the nickname.

Balducci, the 2025 Giants of Cancer Care Supportive, Palliative, and/or Geriatric Care inductee,…

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (“CDC”) Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (“ACIP”) develops recommendations for how vaccinations are used to control disease in the United States. Earlier this month, the ACIP

As cesarean delivery (C-section) rates continue to rise worldwide, experts at NYU Langone Health are highlighting a surgical technique that may help lower the risk of long-term complications. The endometrium-free closure technique (EFCT),

Quantum Biopharma has completed dosing in two toxicology studies requested by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) that aim to support the launch of clinical studies of Lucid-MS, an experimental treatment for multiple sclerosis (MS)…

Attention disorders such as ADHD occur when the brain has trouble separating meaningful signals from constant background input. The brain continuously processes sights, sounds, and internal thoughts, and focus depends on its ability to ignore…