Published in PNAS, the study shows that plants use the hormone abscisic acid (ABA) as a fast‑track messaging system. When temperatures drop, maternal tissues increase ABA production and deliver it to the developing seed. This early hormonal…

Category: 6. Health

-

Expanded vaccine supply allows resumption of cholera prevention campaigns

Global cholera vaccine supply has now increased to a level sufficient to allow the resumption of life-saving preventive campaigns for the first time in over three years, Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, UNICEF, and the World Health…

Continue Reading

-

Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Researchers Find New Way to Slow Memory Loss in Alzheimer’s

COLD SPRING HARBOR, N.Y., Feb. 5, 2026 /PRNewswire/ — Alzheimer’s disease is often measured in statistics: millions affected worldwide, cases rising sharply, costs climbing into the trillions. For families, the disease is…

Continue Reading

-

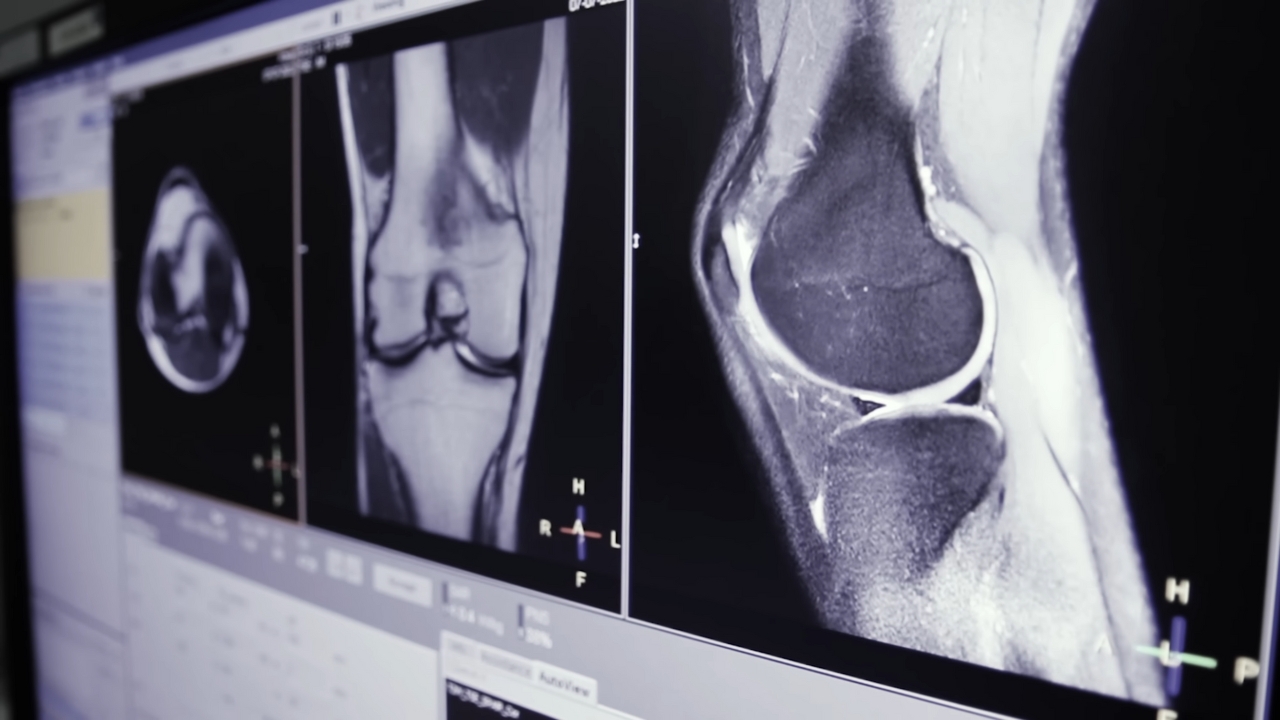

Scientists Just Found a Way to Regrow Cartilage Without Stem Cells, And It Could Change Arthritis Treatment Forever

Scientists have identified a promising new method to regenerate cartilage by targeting a single enzyme linked to aging, a finding that could eventually change how osteoarthritis and joint damage are treated.

The study, published in…

Continue Reading

-

Liver Model Advances Drug Discovery for Fatty Liver Disease

More than 100 million people in the United States suffer from metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), characterized by a buildup of fat in the liver. This condition can lead to the development of more severe liver…

Continue Reading

-

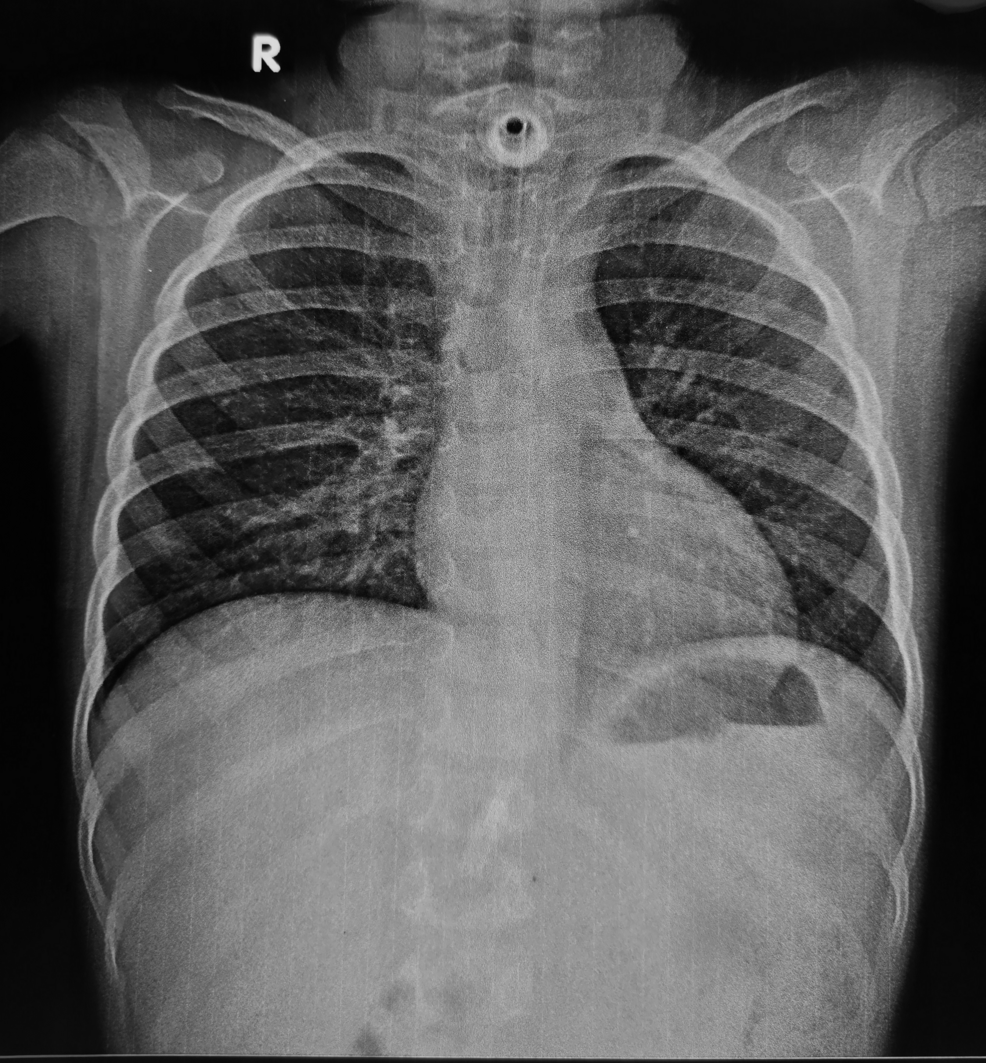

New AI tool predicts repeat heart attack risk for cancer patients

image: ©peterschreiber.media | iStock A new AI-powered tool can predict the risk of another heart attack in patients with cancer, helping doctors tailor care and improve outcomes, according to HDR UK and The Lancet

The…

Continue Reading

-

What decades of tobacco regulation can teach us about ultra-processed food, new study finds

Ultra-processed foods, like tobacco, are engineered to heighten reward, drive compulsive consumption, and potentially create addiction, and should therefore be regulated as such, a new study suggests.

Researchers from Harvard, Duke, and…

Continue Reading

-

New Standard for Hexavalent Chromium Analysis: Improving Accuracy with synchrotron X-ray Technology

Newswise — A team of Korean researchers has developed a reference material that significantly improves the accuracy of analyzing hexavalent chromium, a Group 1 carcinogen that can be present in groundwater and…

Continue Reading