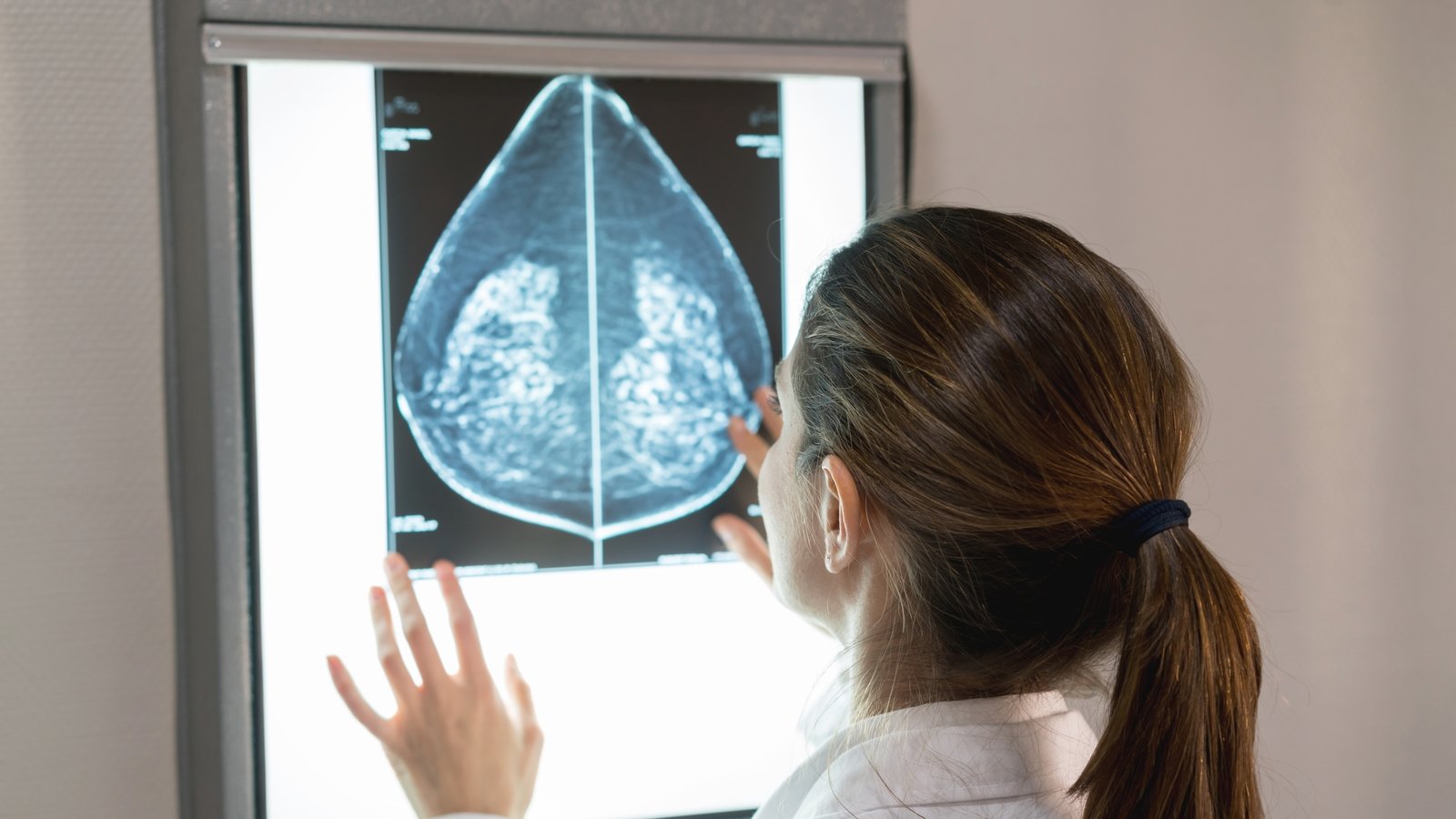

The Irish Cancer Society is urging people to avail of the appropriate cancer screenings for their age and for those who suspect any symptoms to visit their GP.

One in two people will get cancer in their lifetime, with…

The Irish Cancer Society is urging people to avail of the appropriate cancer screenings for their age and for those who suspect any symptoms to visit their GP.

One in two people will get cancer in their lifetime, with…

Multi-hyphenate artist Donald Glover, also known by his stage name Childish Gambino, has five Grammy Awards, two Emmys and, at 42, one stroke.

“I was doing this world tour,” he said at a November concert…

If back pain can be reliably prevented, not only will quality of life be improved, but it will also directly lead to a reduction in health care costs for society as a whole. According to the research team, back pain is one of the most common…

The number of people in hospital with flu in England has fallen for the second week in a row, NHS figures show, as England’s top doctor said the health service was “far from complacent” as a cold snap takes hold.

An average of 2,676 flu…

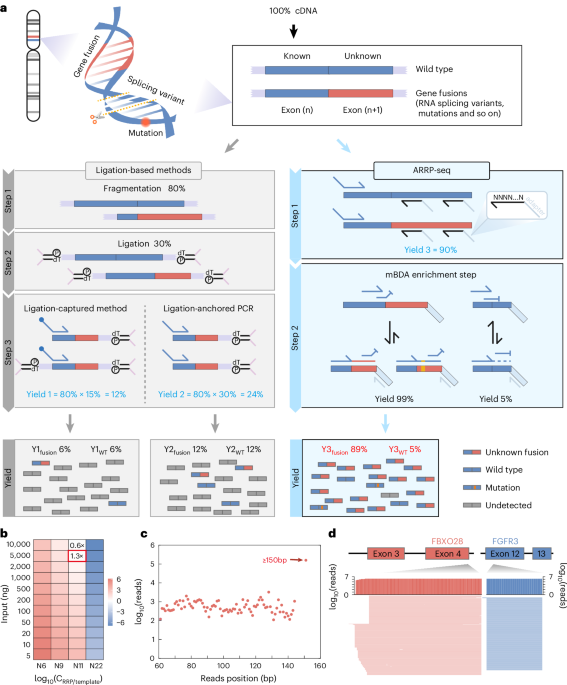

Gao, Q. et al. Driver fusions and their implications in the development and treatment of human cancers. Cell Rep. 23, 227–238.e3 (2018).

Google Scholar

…

Health visitors in some areas are set to offer vaccinations to children who have ‘fallen through the cracks’ as part of a one-year pilot programme.

The government has unveiled plans for a £2m pilot where health visitors will…

In 2025, the NeurologyLive® staff was a busy bunch, covering clinical news and data readouts from around the world across a number of key neurology subspecialty areas. From major study publications and FDA decisions to societal conference…

A LARGE two-sample Mendelian randomisation (MR) study provides strong genetic evidence that increased body mass index (BMI) causally increases the risk of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS), while the role of smoking remains unclear. The study also…

But the laws, all passed this year, don’t fully address the fast-changing landscape of AI software development. And app developers, policymakers and mental health advocates say the resulting patchwork of state laws isn’t enough to…