Health visitors in some areas are set to offer vaccinations to children who have ‘fallen through the cracks’ as part of a one-year pilot programme.

The government has unveiled plans for a £2m pilot where health visitors will…

Health visitors in some areas are set to offer vaccinations to children who have ‘fallen through the cracks’ as part of a one-year pilot programme.

The government has unveiled plans for a £2m pilot where health visitors will…

In 2025, the NeurologyLive® staff was a busy bunch, covering clinical news and data readouts from around the world across a number of key neurology subspecialty areas. From major study publications and FDA decisions to societal conference…

A LARGE two-sample Mendelian randomisation (MR) study provides strong genetic evidence that increased body mass index (BMI) causally increases the risk of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS), while the role of smoking remains unclear. The study also…

But the laws, all passed this year, don’t fully address the fast-changing landscape of AI software development. And app developers, policymakers and mental health advocates say the resulting patchwork of state laws isn’t enough to…

Approximately 8.7 million people in the UK work night shifts, but humans are not meant to be awake at night. “It goes against our natural circadian cycle,” says Steven Lockley, visiting professor at the Surrey Sleep Research Centre,…

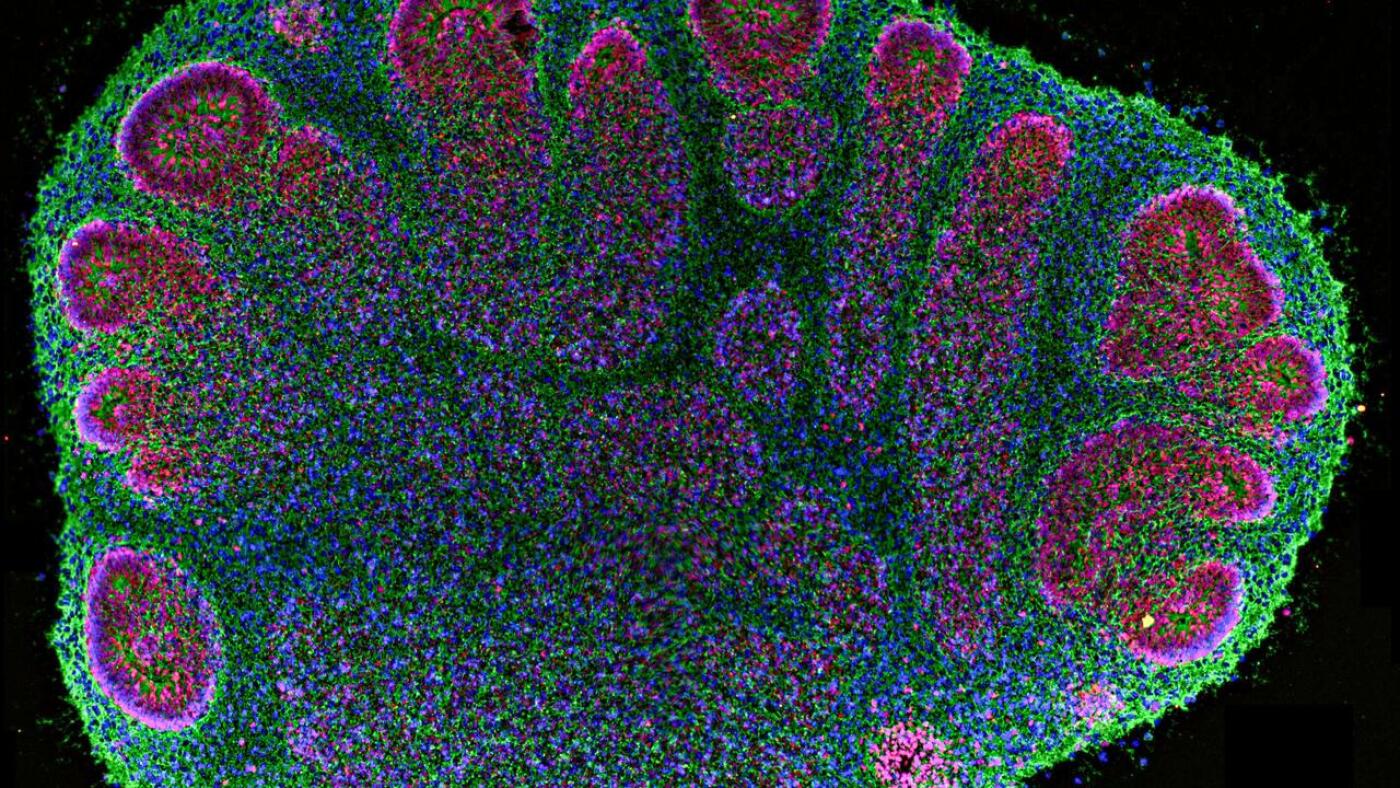

Cross-section of a two-month old cerebral organoid observed under a fluorescence microscope.

…

Soybean oil, the most widely used cooking oil in the United States, contributes to obesity through a specific genetic mechanism, according to a new study from UC Riverside.

Published in the Journal of Lipid Research, the study explains why…

The recent threat and introduction of tariffs by the US government has caused severe economic turbulence globally. Tariffs can increase prices, disrupt trade, cause stock market volatility, threaten jobs and businesses that rely on exports, and…

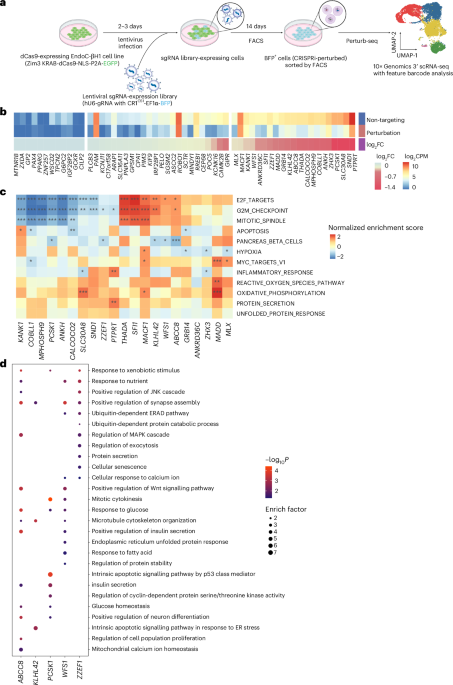

Suzuki, K. et al. Genetic drivers of heterogeneity in type 2 diabetes pathophysiology. Nature 627, 347–357 (2024).

Google Scholar

Mahajan, A. et al….

World Health Organization. https://go.nature.com/3IUuBi2 (2024).

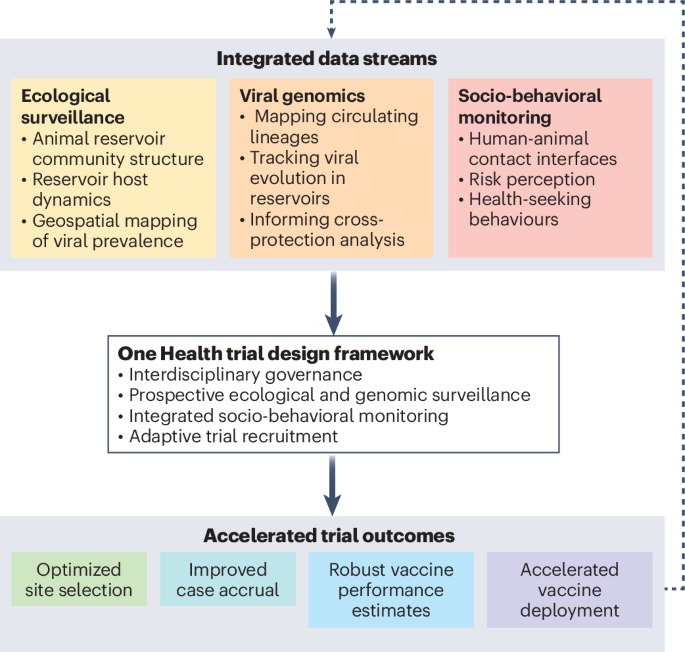

Gouglas, D. et al. Lancet Glob. Health 6, e1386–e1396 (2018).

Google Scholar

Warimwe, G. M. et…