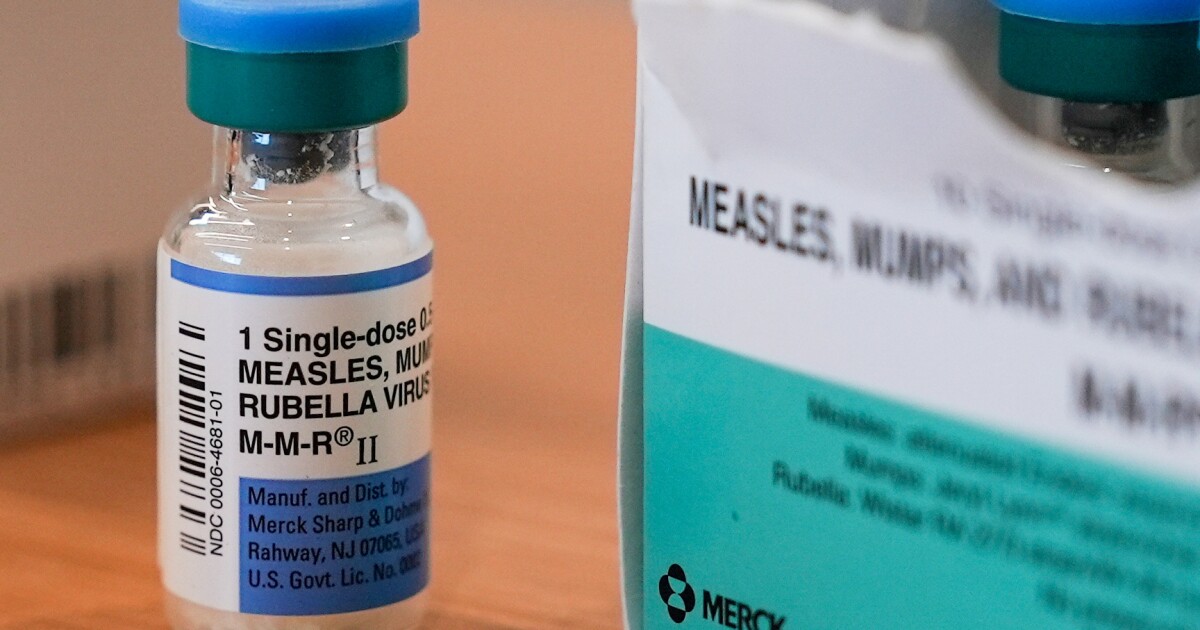

The North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services announced a case of measles on Wednesday in a child in Polk County. It’s the second case in the state this year and the first related to an…

Category: 6. Health

-

UNM Health Sciences celebrates a year of groundbreaking research and health care expansion in 2025

At The University of New Mexico’s Health Sciences Center (HSC), 2025 was a year of groundbreaking research.

Making up the bulk of the top 10 most-viewed stories on the HSC Newsroom were articles detailing the efforts of the HSC’s bold…

Continue Reading

-

Mississippi experiences explosive growth in maternal syphilis

Diligent public health efforts nearly eliminated syphilis 20 years ago.

Stopping outbreaks involved extensive testing and treatments for the sexually transmitted infection (STI) in affected people, as well as tracing, testing, and treating their…

Continue Reading

-

Trial: Next-day HIV viral load test results didn’t boost care-seeking for antiretroviral therapy, prevention

A randomized clinical trial led by Johns Hopkins researchers finds that giving patients a next-day HIV viral load (VL) test result didn’t improve rates of care-seeking for antiretroviral therapy (ART) or HIV preexposure prophylaxis…

Continue Reading

-

Trial: Next-day HIV viral load test results didn’t boost care-seeking for antiretroviral therapy, prevention

A randomized clinical trial led by Johns Hopkins researchers finds that giving patients a next-day HIV viral load (VL) test result didn’t improve rates of care-seeking for antiretroviral therapy (ART) or HIV preexposure prophylaxis…

Continue Reading

-

Hospital officials encourage vaccination as flu cases surge and EDs overcrowd

If it seems like a lot of people have been sick lately, you’re not imagining things.

Hospital officials said Wednesday that this flu season is the most severe they’ve seen in the past couple of years,…

Continue Reading

-

New Drug Approach Targets KRAS-Mutant Lung Cancer to Overcome Therapy Resistance

University of Michigan researchers reveal a promising approach for hard-to-treat lung cancers that combines a molecular glue with KRAS inhibitors to delay resistance—leading to dramatic tumor shrinkage in lab models.

Lung cancer remains the…

Continue Reading

-

Idaho notes first CWD case in Hunting Unit 15

CDC Today, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that the country’s confirmed measles cases have grown to 2,065, up from 2,012 last week, with outbreaks in South Carolina, Arizona, and Utah each documenting 10 to…

Continue Reading