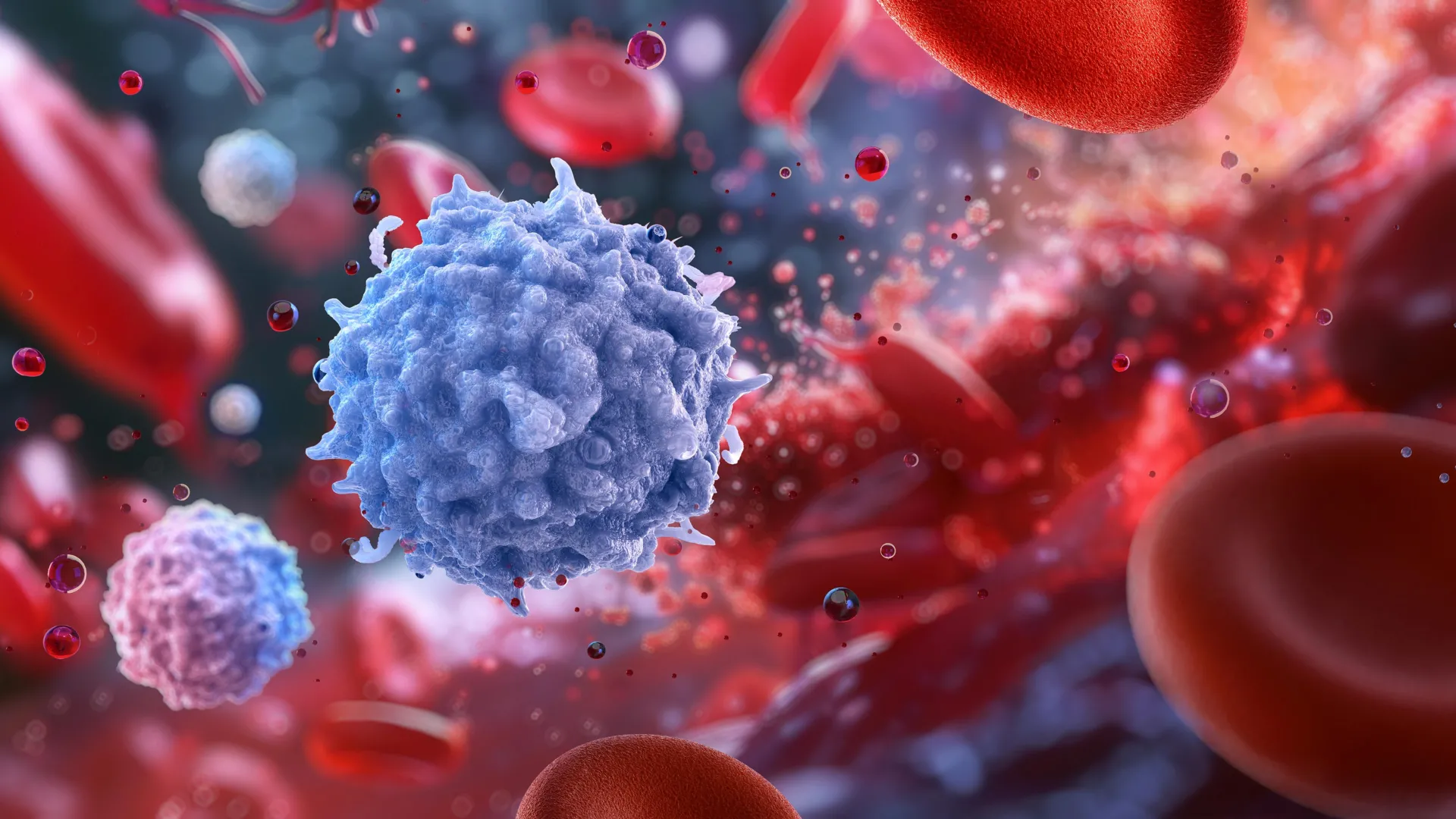

As people grow older, visible changes like gray hair and weaker muscles are only part of the story. Aging also affects the immune system. One major reason is that the stem cells responsible for producing blood and immune cells can accumulate…

As people grow older, visible changes like gray hair and weaker muscles are only part of the story. Aging also affects the immune system. One major reason is that the stem cells responsible for producing blood and immune cells can accumulate…