Category: 6. Health

-

Film raises empathy and awareness for youths with virus

Students hold a red ribbon, the symbol of AIDS support, during an event to raise awareness about the virus at the University of South China in Hengyang, Hunan province, in November.[Photo provided by Cao… -

The brain has a hidden language and scientists just found it

Scientists have developed a protein that can record the chemical messages brain cells receive, rather than focusing only on the signals they send out. These incoming signals are created when neurons release glutamate, a neurotransmitter that…

Continue Reading

-

The brain has a hidden language and scientists just found it

Scientists have developed a protein that can record the chemical messages brain cells receive, rather than focusing only on the signals they send out. These incoming signals are created when neurons release glutamate, a neurotransmitter that…

Continue Reading

-

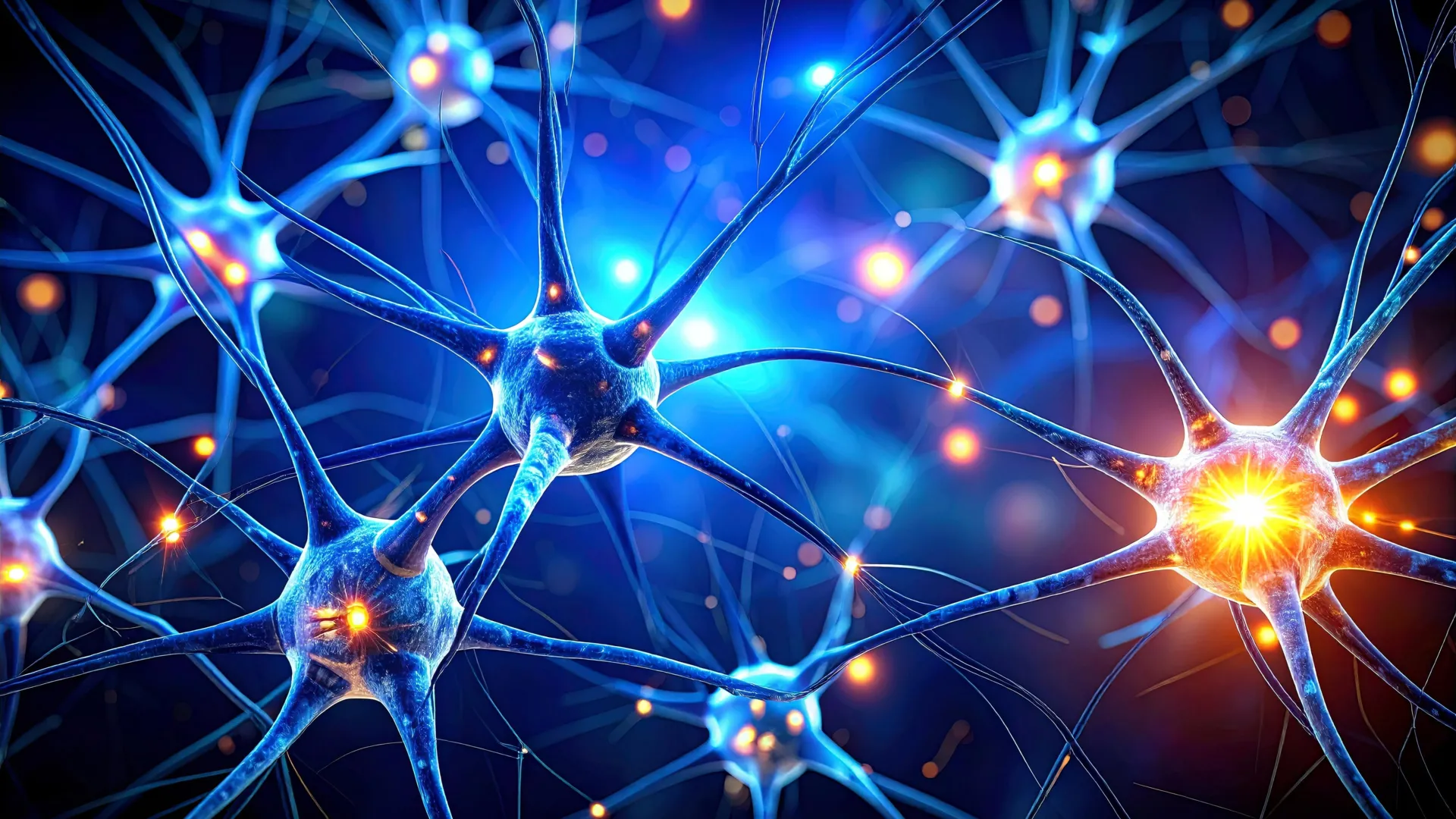

Mexico confirmed measles total tops 6,000 cases in 2025

According to the Mexico Ministry of Health, 6,050 cumulative confirmed cases of measles from 29 states and 207 municipalities through December 26 this year.

Of the confirmed cases*, states reporting the most include Chihuahua (4,481), Jalisco…

Continue Reading

-

Journal of Medical Internet Research

Introduction

There is limited research examining the sexual and reproductive health (SRH) experiences of cisgender, lesbian, bisexual, and queer (LBQ+) women of color in the United States. Historically, research about the SRH experiences of sexual…

Continue Reading

-

U.S. Surpasses 2,000 Measles Cases This Year—Most Since 1992 – Forbes

- U.S. Surpasses 2,000 Measles Cases This Year—Most Since 1992 Forbes

- Newark Airport passenger may have exposed others to measles, New Jersey Health Department says ABC7 New York

- Holiday travelers at US airport ‘exposed to world’s most infectious…

Continue Reading

-

ADHD is more complex than we once believed: Find out how

Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, or ADHD in short, is a long-term condition that…

Continue Reading

-

Nirsevimab may help prevent severe respiratory illnesses beyond RSV in infants, young kids

In addition to reducing respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)–related hospitalizations and emergency department (ED) visits, nirsevimab (Beyfortus) may also reduce these events when they’re linked to other lower respiratory tract infections…

Continue Reading

-

Researchers harness cancer resistance mutations to fight tumors-Xinhua

JERUSALEM, Dec. 29 (Xinhua) — An international team of researchers has discovered a new method to fight cancers that no longer respond to treatment, using the very mutations that make tumors drug-resistant, Israel’s Weizmann Institute of…

Continue Reading

-

There are new antivirals being tested for herpesviruses. Scientists now know how they work

At a glance:

- Study uncovers key insights about how a new class of antiviral drugs works.

- Cryo-EM images showed the drugs bound to herpes simplex virus (HSV) protein at nearly atomic detail, while…

Continue Reading