Introduction

Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) belongs to a chronic metabolic disorder with a rapidly escalating global incidence, primarily attributed to contemporary lifestyle factors such as excessive consumption of energy-rich diets and…

Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) belongs to a chronic metabolic disorder with a rapidly escalating global incidence, primarily attributed to contemporary lifestyle factors such as excessive consumption of energy-rich diets and…

The question of whether environmental factors can alter traits in future generations through epigenetic changes rather than DNA sequence mutations has long been controversial in genetics. Observations of disease and metabolic changes in offspring…

Thailand is undergoing a profound demographic and epidemiologic transition. By 2023, about 12 million Thais (18% of the population) were aged 60 or above, qualifying Thailand as an “aged society,” with projections of the elderly…

Epilepsy is a chronic neurological disorder characterized by recurrent, unprovoked seizures due to abnormal electrical activity in the brain. It affects millions of individuals globally, with diverse etiologies and clinical…

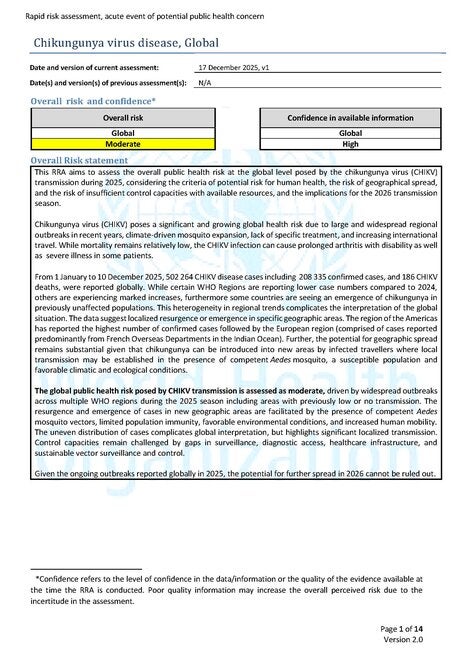

This Rapid Risk Assessment (RRA) aims to assess the risk of chikungunya virus disease at the global level, considering the public health impact, the risk of geographical spread and the risk of insufficient control capacities with available…

Pneumonia is frequently observed in clinical settings and is typically caused by pathogens such as influenza A and B viruses, coronaviruses including SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and SARS-CoV-2, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Candida albicans,…

Infertility (defined as the inability to conceive after 1 year of unprotected intercourse) affects 10–15% of reproductive-aged women globally, with etiologies including ovulatory dysfunction, endometriosis, and tubal pathologies.

Hongping Lu,1,2,* Haoke Shi,1,* Yao Chen,1 Chun Zhang,3 Xi Chen,3 Xiaohong Zhang,4 Xinhong Yin1

1School of Nursing, University of South China, Hengyang, Hunan, People’s Republic of China; 2Department of Pain Medicine, Hubei Provincial…

Tiny fragments of plastic are making their way deep inside our bodies in concerning quantities, particularly through our food and drink.

In 2024, scientists in China found a simple and effective means of removing them from water. The team ran…