Category: 6. Health

-

Meta, YouTube, Snap, TikTok respond to social media allegations | MLex

( December 23, 2025, 22:05 GMT | Official Statement) — MLex Summary: The four large social media companies — Meta Platforms, YouTube, Snap* — accused of triggering a mental health crisis among US teens by building addictive…

Continue Reading

-

Meta, YouTube, Snap, TikTok respond to social media allegations | MLex

( December 23, 2025, 22:05 GMT | Official Statement) — MLex Summary: The four large social media companies — Meta Platforms, YouTube, Snap* — accused of triggering a mental health crisis among US teens by building addictive…

Continue Reading

-

A Simple Way to Test Longevity

5 ways to improve your score on the sitting-rising test

Data from Araújo’s clinic shows that scores on the sitting-rising test tend to decline with age, with fewer than 8 percent of adults ages…

Continue Reading

-

Chile confirms detection of influenza A(H3N2) subclade K

The Ministry of Health, through the Public Health Institute (ISP), reports the detection of influenza A(H3N2) subclade K in samples analyzed in the country. This finding was expected given the global epidemiological behavior of the virus and…

Continue Reading

-

Early Release – Macrolide Resistance and P1 Cytadhesin Genotyping of Mycoplasma pneumoniae during Outbreak, Canada, 2024–2025 – Volume 31, Number 12—December 2025 – Emerging Infectious Diseases journal

Disclaimer: Early release articles are not considered as final versions. Any changes will be reflected in the online version in the month the article is officially released.

Author affiliation: McMaster University, Hamilton,…Continue Reading

-

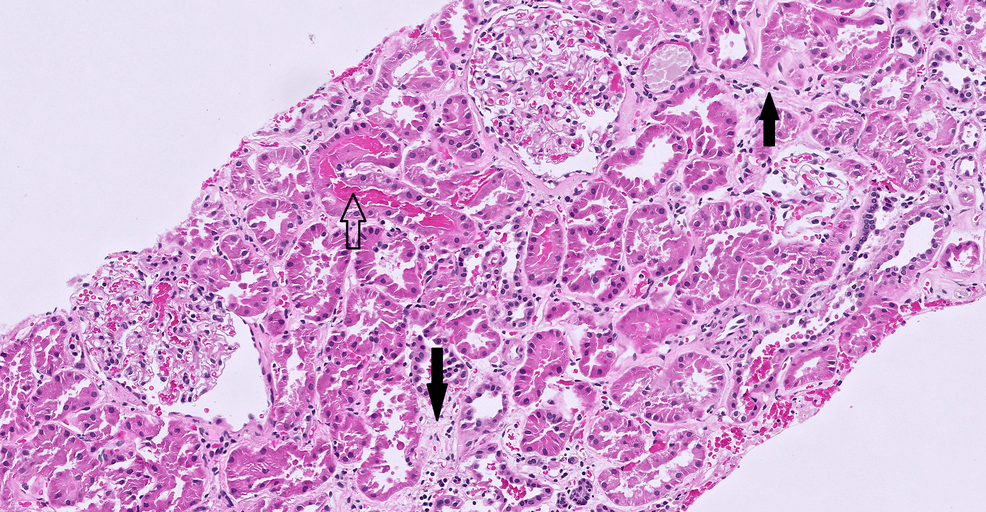

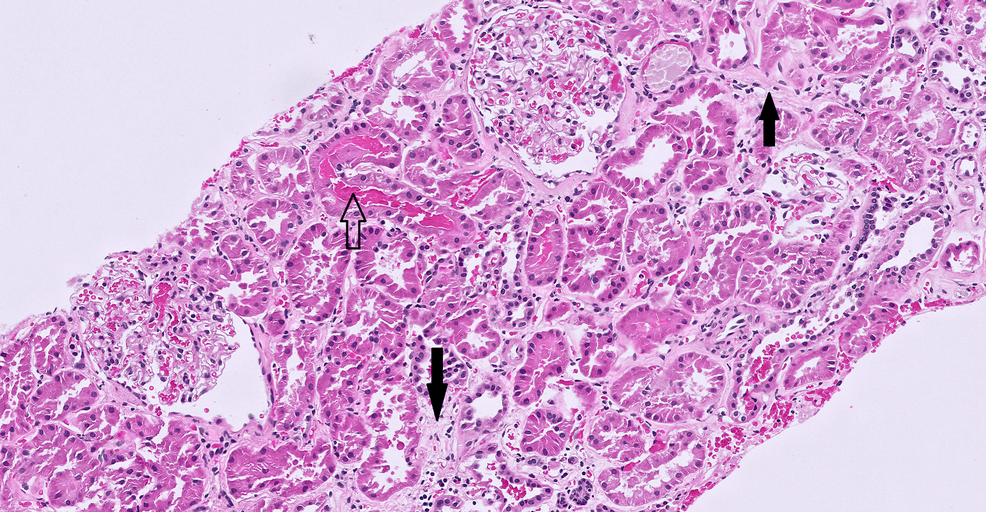

Early Release – Guinea Pig Model for Lassa Virus Infection of Reproductive Tract and Considerations for Sexual and Vertical Transmission – Volume 31, Number 12—December 2025 – Emerging Infectious Diseases journal

Disclaimer: Early release articles are not considered as final versions. Any changes will be reflected in the online version in the month the article is officially released.

Author affiliation: Centers for Disease Control and…Continue Reading

-

Early Release – Guinea Pig Model for Lassa Virus Infection of Reproductive Tract and Considerations for Sexual and Vertical Transmission – Volume 31, Number 12—December 2025 – Emerging Infectious Diseases journal

Disclaimer: Early release articles are not considered as final versions. Any changes will be reflected in the online version in the month the article is officially released.

Author affiliation: Centers for Disease Control and…Continue Reading

-

Early Release – Silent Propagation of Classical Scrapie Prions in Homozygous K222 Transgenic Mice – Volume 31, Number 12—December 2025 – Emerging Infectious Diseases journal

Disclaimer: Early release articles are not considered as final versions. Any changes will be reflected in the online version in the month the article is officially released.

Author affiliation: Centro de Investigación en…Continue Reading