Category: 6. Health

-

Non-native birds drive widespread avian malaria transmission in Hawaii

New research on avian malaria, which has decimated Hawaii’s beloved birds, explains how non-native birds play a key role in transmission and contribute to the widespread distribution of the disease. This disease threatens many…

Continue Reading

-

Researchers uncover mechanisms of three mismatch repair deficient high-grade glioma subtypes

Researchers have uncovered the mechanisms behind three unique subtypes of mismatch repair deficient high-grade gliomas. The findings provide a clearer understanding of how these tumors develop, explain why patients…

Continue Reading

-

How Health Budget Cuts Are Harming People With HIV Around the World – Pulitzer Center

- How Health Budget Cuts Are Harming People With HIV Around the World Pulitzer Center

- US Approves $6 Billion Towards Ending HIV/AIDS NY Carib News

- HIV Spending for Fiscal Year 2026: The Latest Update Contagion Live

- US allocates $5.9 billion for…

Continue Reading

-

Alzheimer Antibody Therapy Denied Approval in Scotland – Medscape

- Alzheimer Antibody Therapy Denied Approval in Scotland Medscape

- Call to rethink approach to Alzheimer’s drugs HealthandCare.scot

- Alzheimer’s campaigners call for dedicated fund as new drug is rejected Morning Star | The People’s Daily

Continue Reading

-

Exercise can be ‘frontline treatment’ for mild depression, researchers say | Mental health

Aerobic exercise such as running, swimming or dancing can be considered a frontline treatment for mild depression and anxiety, according to research that suggests working out with others brings the most benefits.

Scientists analysed published…

Continue Reading

-

Advances in MASLD and MASH Care Highlight Progress and Persistent Gaps

The rapid rise of metabolic disease has transformed fatty liver disease into one of the most common chronic liver conditions worldwide, forcing clinicians and payers alike to confront gaps in how

metabolic dysfunction–associated… Continue Reading

-

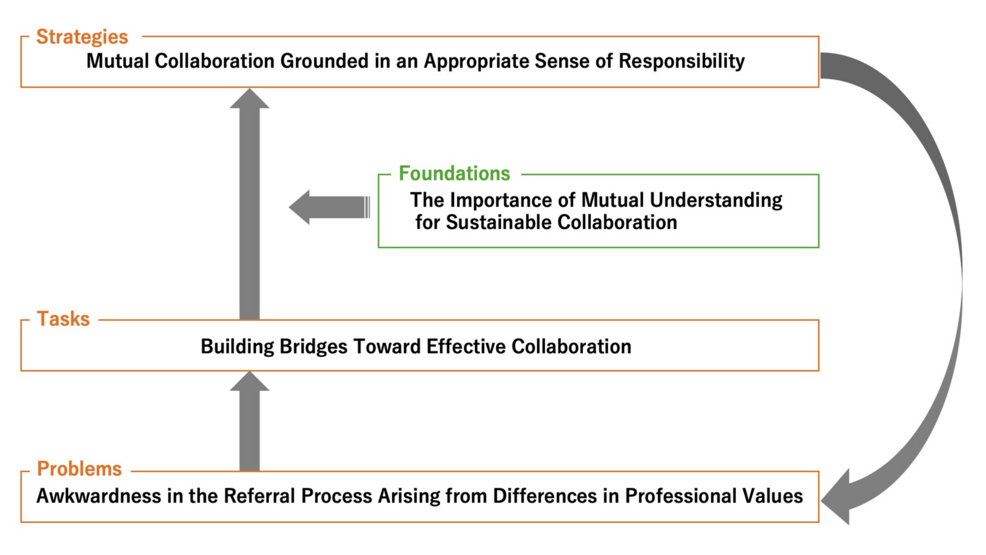

Eye Disease Care Links With Addiction Services

Eric Gaier, MD, PhD, and Dean Eliott, MD, of the Department of Ophthalmology at Mass Eye and Ear, a member of the Mass General Brigham healthcare system, are co-authors of a paper published in Ophthalmology Retina, ” Substance Use…

Continue Reading

-

Genetics of Anxiety: Landmark Study Reveals Risks

Anxiety disorders — including generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder and phobias — affect as many as one in four people over the course of their lives. They often begin early in life and persist for years, inflicting…

Continue Reading

-

What Nurses Should Know About Metastasis-Directed Therapy for Oligometastatic Prostate Cancer

In a recent study, investigators compared treatment protocols for oligometastatic prostate cancer, analyzing metastasis-directed therapy (MDT) plus the standard of care (SOC) versus SOC alone to discern the overall effectiveness of MDT for this…

Continue Reading