Artificial intelligence helps doctors spot more cases of breast cancer when reading routine scans, a world-first trial found Friday.

The results suggest countries should roll out programmes taking advantage of AI’s scanning power to ease the…

Artificial intelligence helps doctors spot more cases of breast cancer when reading routine scans, a world-first trial found Friday.

The results suggest countries should roll out programmes taking advantage of AI’s scanning power to ease the…

CANBERRA, Jan. 30 (Xinhua) — Australia’s health minister said on Friday that the government is closely monitoring the outbreak of the Nipah virus in Asia.

Mark Butler told Nine Network television that the Nipah virus has never been detected…

MEHR (Dunya News) – Authorities have failed to control a dangerous throat virus in Mehar, an area of interior Sindh, as another child has died after prolonged illness.

Twelve-year-old Asif Ali Jiskani, a resident of…

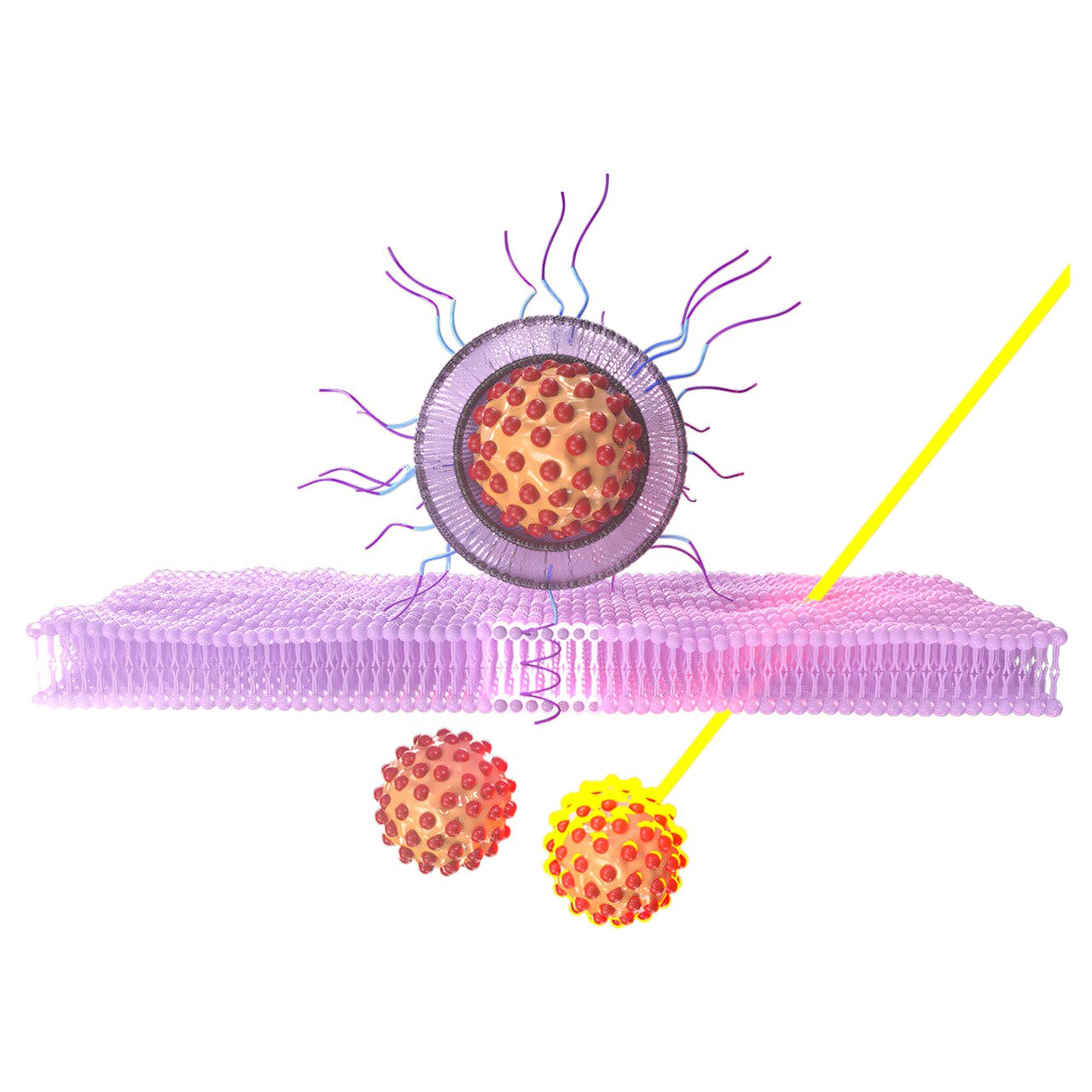

Researchers at NYU Abu Dhabi have developed a new light-based…

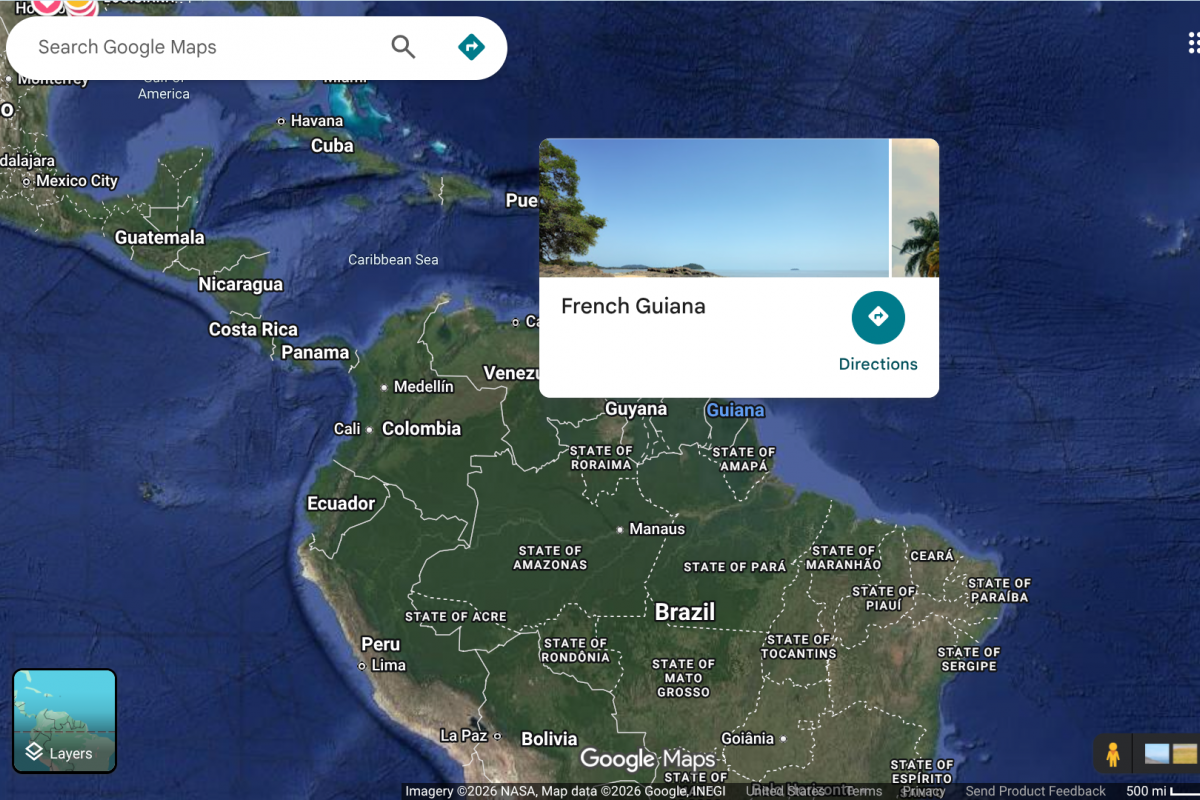

The Regional Health Agency (ARS) of French Guiana has announced the detection of the territory’s first locally acquired case of chikungunya. The individual, who had not traveled in the 15 days before the onset of…

Drinking a few cups of coffee a day is actually good for you, but new research suggests that when you sip makes all the difference when it comes to heart health and longevity. The 2025 study, published in the European Heart Journal, was the…

Having had a stroke caused by blocked blood vessels (ischemic stroke) more than doubled an expectant mother’s odds of having another stroke during pregnancy and within six weeks of childbirth, according to a preliminary study to…

– Advertisement –

– Advertisement –

– Advertisement –

ABU DHABI, Jan 29 (WAM/APP): Researchers at NYU Abu Dhabi (NYUAD) have developed a new light-based nanotechnology that could improve how certain cancers are detected and treated, offering a…