Two NHS Tayside specialists have put themselves on a pureed diet to gain an insight into the difficulties faced by patients with head and neck cancers.

Specialist Speech and Language Therapist, Sinéad McCarney, and Specialist Oncology…

Two NHS Tayside specialists have put themselves on a pureed diet to gain an insight into the difficulties faced by patients with head and neck cancers.

Specialist Speech and Language Therapist, Sinéad McCarney, and Specialist Oncology…

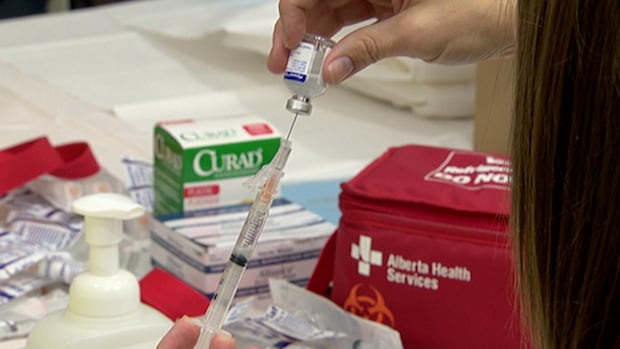

The CDC has reported nearly 2000 measles cases to date in 2025, a number we haven’t seen since 1992.

Next month, the US faces a critical deadline where we have to prove that we have stopped measles transmission, if not, we could lose our…

Listen to this article

Estimated 4 minutes

The audio version of this article is generated by AI-based technology. Mispronunciations can occur. We are working with our partners to continually review and improve the results.

As the holidays creep…

The 2025 Union World Conference on Lung Health held on 18-21 November 2025 in Copenhagen, Denmark featured more than 20 sessions showcasing the latest on TB vaccines, from innovations in clinical development to growing implementation and…

Treatment Action Group (TAG) released a report providing a first-of-its-kind analysis of the global supply chains of QS-21 and MPL, two adjuvants used in licensed vaccines against malaria, shingles, respiratory syncytial virus,…

A small Japanese study suggests that a low-salt, oat-based granola breakfast may improve blood pressure, lipid risk markers, and gut health indicators in people with moderate chronic kidney disease, while highlighting the need for…

A large community study shows that Alzheimer’s-related brain changes are far more widespread with age than symptoms alone suggest, highlighting both the promise and the complexity of blood-based screening.

Study: Prevalence of…

SAN ANTONIO – The Kerrville Renaissance Festival is set to kick off another season, promising a vibrant array of family-friendly entertainment and activities!

The festival will take place over three weekends from Jan. 17 to Feb. 1 at the River…