Category: 6. Health

-

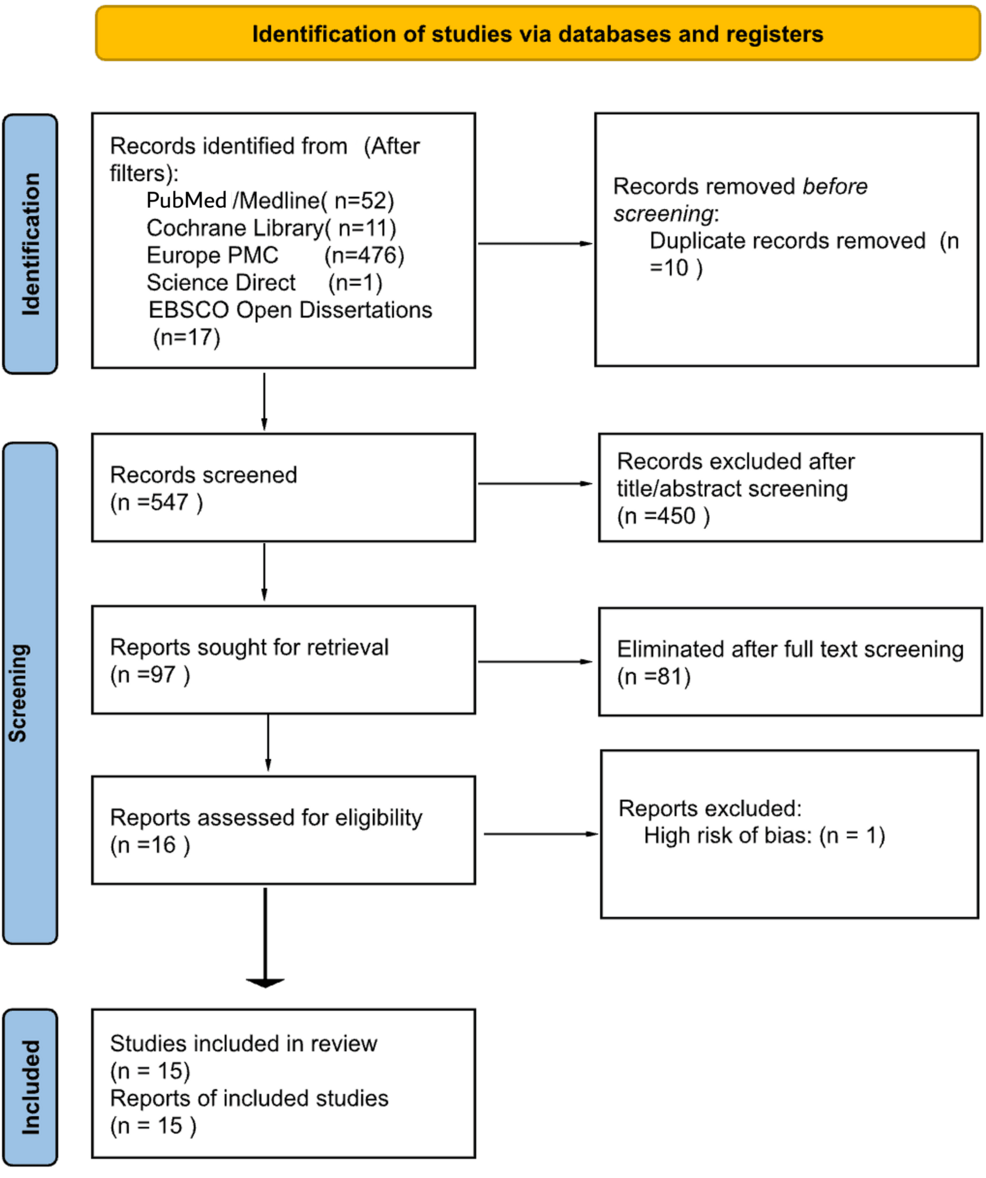

Ethiopia reports additional recovery in Marburg outbreak

The Ethiopia Ministry of Health reported the following update on the Marburg Virus Disease (MVD) outbreak today:

No new confirmed cases or deaths that day but one additional recovery, bringing totals to 14 confirmed cases, 9 deaths, and 5…

Continue Reading

-

This vaccine adviser to RFK Jr. has some choice words for his critics – Politico

- This vaccine adviser to RFK Jr. has some choice words for his critics Politico

- RFK Jr is a danger to public health – but local Maha laws could be a bigger threat | Katrina vanden Heuvel The Guardian

- The United States CDC has abandoned science…

Continue Reading

-

Bird flu found in Wisconsin dairy herd for first time

Officials said they have found bird flu in a Wisconsin dairy herd for the first time.

Tests of cow’s milk from a Dodge County farm were positive for the highly contagious virus, officials with the Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer…

Continue Reading

-

Montreal doctor says flu season is in full swing – CTV News

- Montreal doctor says flu season is in full swing CTV News

- Severe flu season started early in Quebec. Here’s what you need to know Yahoo News Canada

- CHEO asks family doctors to step up flu-fighting efforts unpublished.ca

- CHEO asks Ottawa doctors…

Continue Reading

-

Brussels Set the Tone, Patients Set the Direction: Action Starts Now – ELPA

European Liver Patients’ Association (ELPA) shared a post on LinkedIn:

“Brussels set the tone. Patients set the direction. Action starts now.

In Brussels, at ‘From Risk to Action: Preventing liver health crises through…

Continue Reading

-

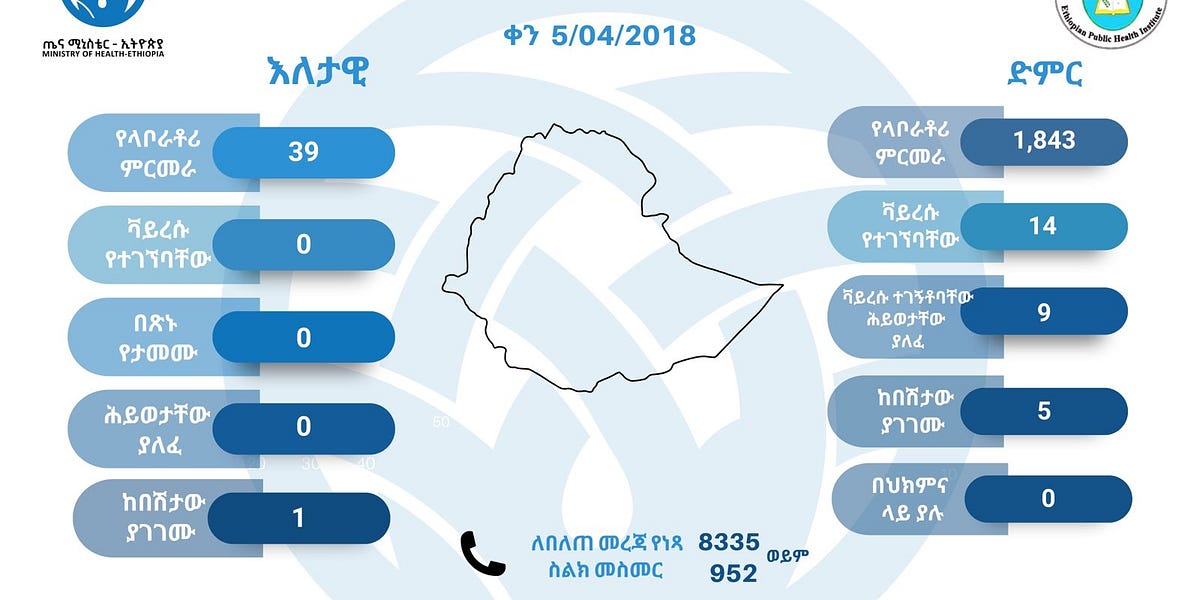

What Makes European Vacationers Sick — Vax-Before-Travel

Europe (Vax-Before-Travel News)Thousands of people across Europe have fallen ill from Listeria this year after eating contaminated food, including eggs, meat, and food products.

A recent European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC)…

Continue Reading

-

Minister appeals to public to get flu jab amid ‘very severe’ strain – The Irish Times

Minister for Health Jennifer Carroll MacNeill has appealed to “everybody who can” to get the flu vaccine, while confirming adults between 18 and 59 and not in at-risk groups will not get the jab for free.

Speaking on RTÉ Radio on Sunday, she…

Continue Reading

-

Avian flu hits Shelby County poultry flock, first Texas case this year

SHELBY COUNTY, Texas (KTRE) – State and federal animal health officials have confirmed highly pathogenic avian influenza in a commercial poultry flock in Shelby County, marking the first confirmed case in a Texas commercial facility this year.

The…

Continue Reading