A study conducted in part by Chicago’s Northwestern Medicine found that tanning beds not only triple the risk of melanoma, but can also damage DNA across nearly the whole skin surface.

Northwestern Medicine and the University of California,…

A study conducted in part by Chicago’s Northwestern Medicine found that tanning beds not only triple the risk of melanoma, but can also damage DNA across nearly the whole skin surface.

Northwestern Medicine and the University of California,…

With dozens of…

A Niverville resident is on edge after seeing dozens of dead geese infected with avian influenza in a retention pond behind her home.

Megan McGregor, 34, knew something wasn’t right when she saw roughly 40 dead…

Forskolin, a plant-derived compound, may offer a meaningful improvement in therapies for a highly aggressive leukemia known as KMT2A-rearranged Acute Myeloid Leukemia (KMT2A-r AML). Researchers at the University of Surrey report that this natural…

Researchers have used a deep learning artificial intelligence model to identify what they describe as the first biomarker of chronic stress that can be directly seen on standard medical images. The findings are being presented next week at the…

NEW research from a major USA child-development study suggests that daily social media use, though often dismissed as harmless, may contribute to small but measurable increases in inattention symptoms over time. The findings, drawn from more…

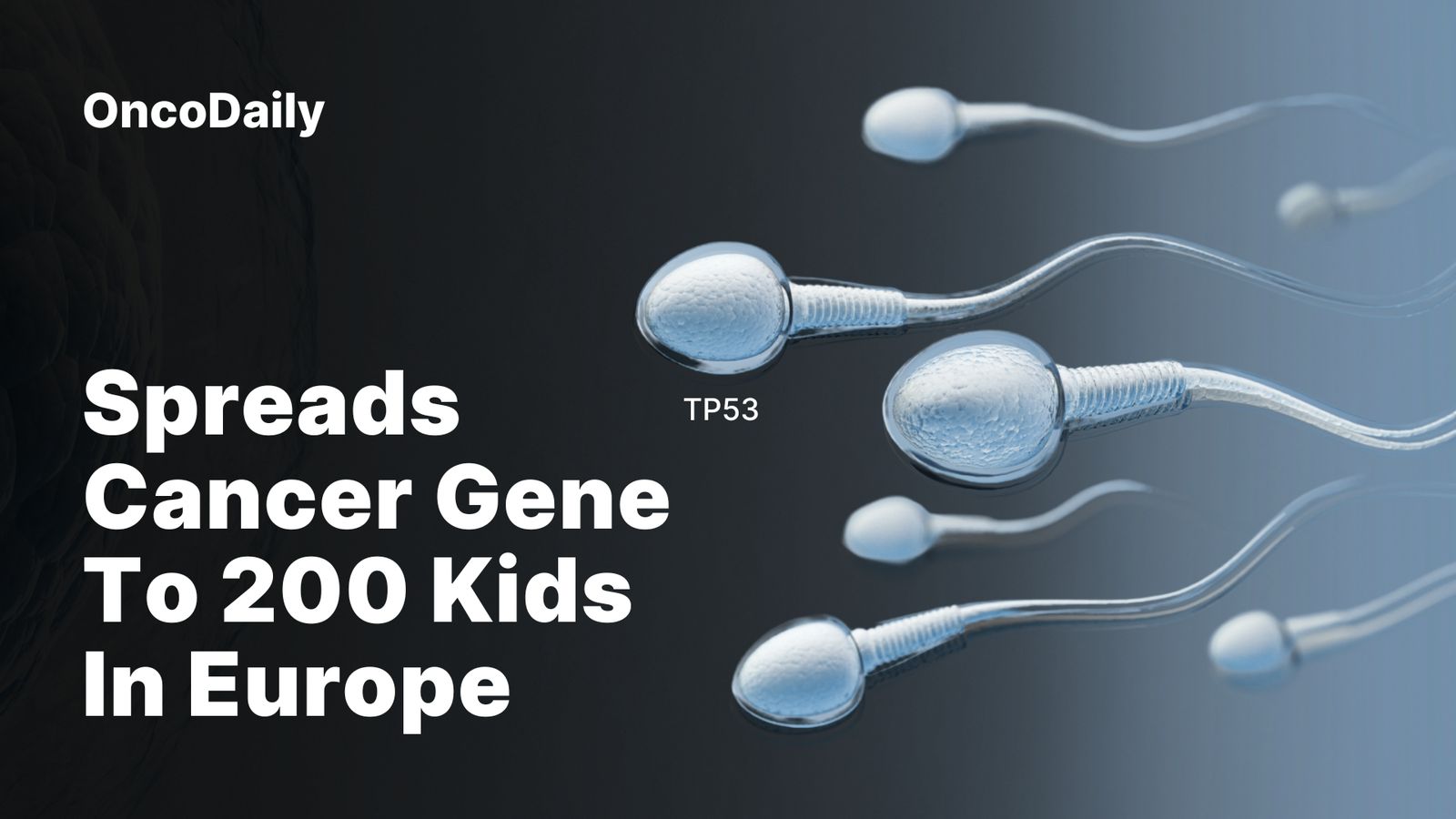

A healthy Danish sperm donor, who passed all standard genetic screenings, fathered nearly 200 children across 14 European countries from 2005 to 2022, unknowingly passing on a TP53 gene mutation in up to 20% of his sperm. This…

Since January 1, 2025, 868 cases of measles have occurred and been reported (an increase of 2 new cases in November). The decline in the number of cases observed since May continued until September and is holding steady until November, in line…