Many of us are still in the reflective stage after

Category: 6. Health

-

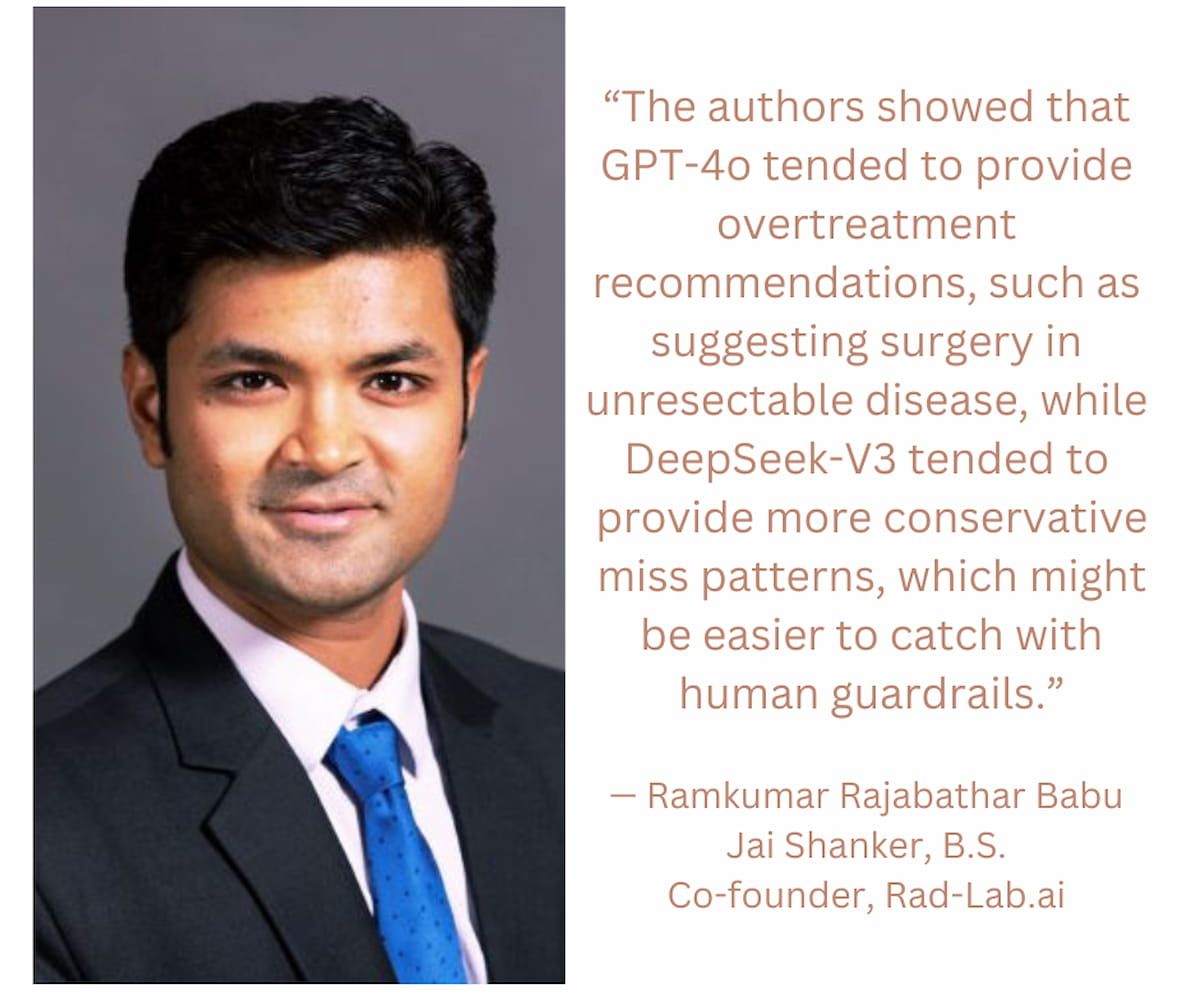

Clinical Applications of LLMs in Radiology: Key Takeaways from RSNA 2025

RSNA 2025 as we attempt to summarize all the fascinating AI-focused sessions, panels, and hallway discussions. Throughout the seven imaging informatics sessions this year, a clear message became… -

Tailoring Low-Protein Diets to Improve CKD Health Outcomes

Protein restriction has been used as a strategy for delaying disease progression in patients with

chronic kidney disease (CKD) for more than 140 years, said the authors of areview article covering research on a low-protein diet in animal models…Continue Reading

-

Gene Therapy Shows Promise Against T-ALL

Original story from the University College London (UCL; UK).

A groundbreaking new treatment using genome-edited immune cells, developed by scientists at UCL and Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH; London UK), has shown promising results in…

Continue Reading

-

Taken correctly, this mineral may shorten your cold – The Washington Post

- Taken correctly, this mineral may shorten your cold The Washington Post

- This popular supplement could shorten the duration of your cold The Independent

- What Happens to Your Cold Symptoms When You Take Vitamin C and Zinc Together Health: Trusted…

Continue Reading

-

Gray hair may have evolved as a protection against cancer, study hints

Graying hair could be a sign that the body is effectively protecting itself from cancer, a new study suggests.

Cancer-causing triggers, such as ultraviolet (UV) light or certain chemicals, activate a natural defensive pathway that leads to…

Continue Reading

-

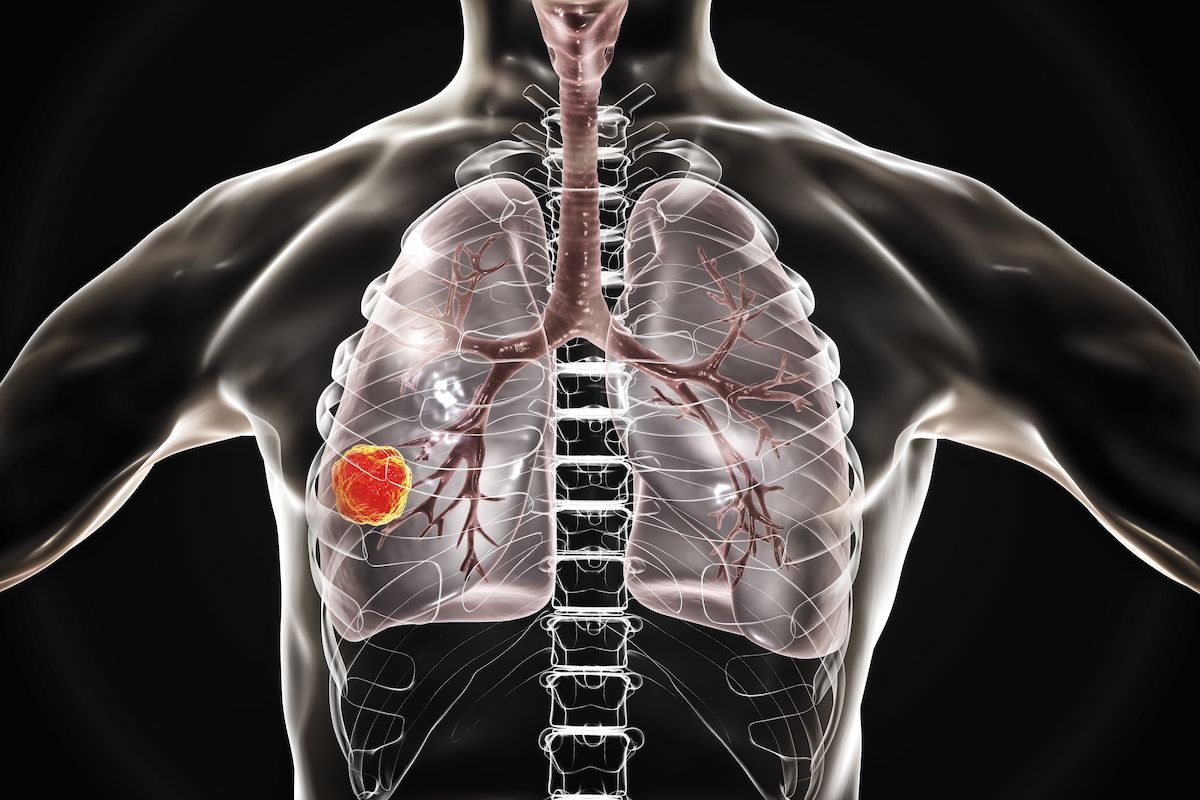

Ivonescimab/Chemo Improves Quality of Life in Frontline Squamous NSCLC

Updated results from the phase 3 HARMONi-6 trial (NCT05840016) demonstrated that patient-reported quality of life outcomes were improved with ivonescimab plus chemotherapy compared with tislelizumab-jsgr (Tevimbra) plus chemotherapy in the…

Continue Reading

-

Astrocyte Diversity Across Space and Time Mapped

When it comes to brain function, neurons get a lot of the glory. But healthy brains depend on the cooperation of many kinds of cells. The most abundant of the brain’s non-neuronal cells are astrocytes, star-shaped cells with a lot of…

Continue Reading

-

Australian researchers pinpoint specific genetic changes linked to severe AMD

Australian researchers have for the first time pinpointed specific genetic changes that increase the risk of severe, sight-threatening forms of age-related macular degeneration (AMD).

A new study, published today in Nature…

Continue Reading

-

Healthcare use patterns for high volume musculoskeletal shoulder disor

Introduction

Shoulder conditions and disorders are commonly experienced musculoskeletal pain conditions and have a prevalence (20.9%) comparable to back (26.9%) and neck pain (20.6%).1 For example, in a 15-year population-based study in the…

Continue Reading

-

UKHSA Detects New Recombinant Mpox Strain in England – Medscape

- UKHSA Detects New Recombinant Mpox Strain in England Medscape

- Inter-Clade Recombinant Mpox Virus Detected in England in a Traveller Recently Returned from Asia Virological

- People have been warned to stay alert facebook.com

- New recombinant…

Continue Reading