Natural experiment data from Wales suggest that shingles vaccination may help lower the risk of cognitive decline and reduce dementia-related deaths, highlighting a potential role for immunisation across the dementia disease…

Category: 6. Health

-

Thinness obsession prompts diet drug misuse in South Korea

December 8, 2025

SEOUL – A wave of demand for weight-loss medication is sweeping South Korea, a country that remains one of the OECD’s leanest, as rising body-image pressure and easy access fuel misuse that concerns health authorities.

At the…

Continue Reading

-

5 Frozen Fruits to Eat for Better Blood Pressure, Per Dietitians

- What you eat can influence blood pressure, and fruit is a great choice.

- Frozen fruits maintain their blood-pressure-friendly nutrients.

- Nosh on avocado, cranberries, wild blueberries, mango and tart cherries.

Managing your blood pressure isn’t…

Continue Reading

-

Investment of Approx. USD 460,000 for the Development of a Prototype Mpox Detection Test with NIPRO, TBA, Japan Institute for Health Security and others USA – English India – English

TOKYO, Dec. 7, 2025 /PRNewswire/ — The Global Health Innovative Technology (GHIT) Fund announced today an investment of approximately JPY 70 million (USD 460,0001) for the…

Continue Reading

-

More women are using steroids – and many don’t know the risks

When people think of gym goers using steroids, the picture that comes to mind is often of a man pumping iron, like Arnold Schwarzenegger, or modern day shirtless masculinity influencers like “the Liver King”.

But the image is changing….

Continue Reading

-

Calcium supplements do not prevent pre-eclampsia, large trials show no meaningful benefit

A new Cochrane systematic review of 10 randomised trials involving over 37,000 pregnant women found that calcium supplementation results in little to no reduction in pre-eclampsia or related adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes.

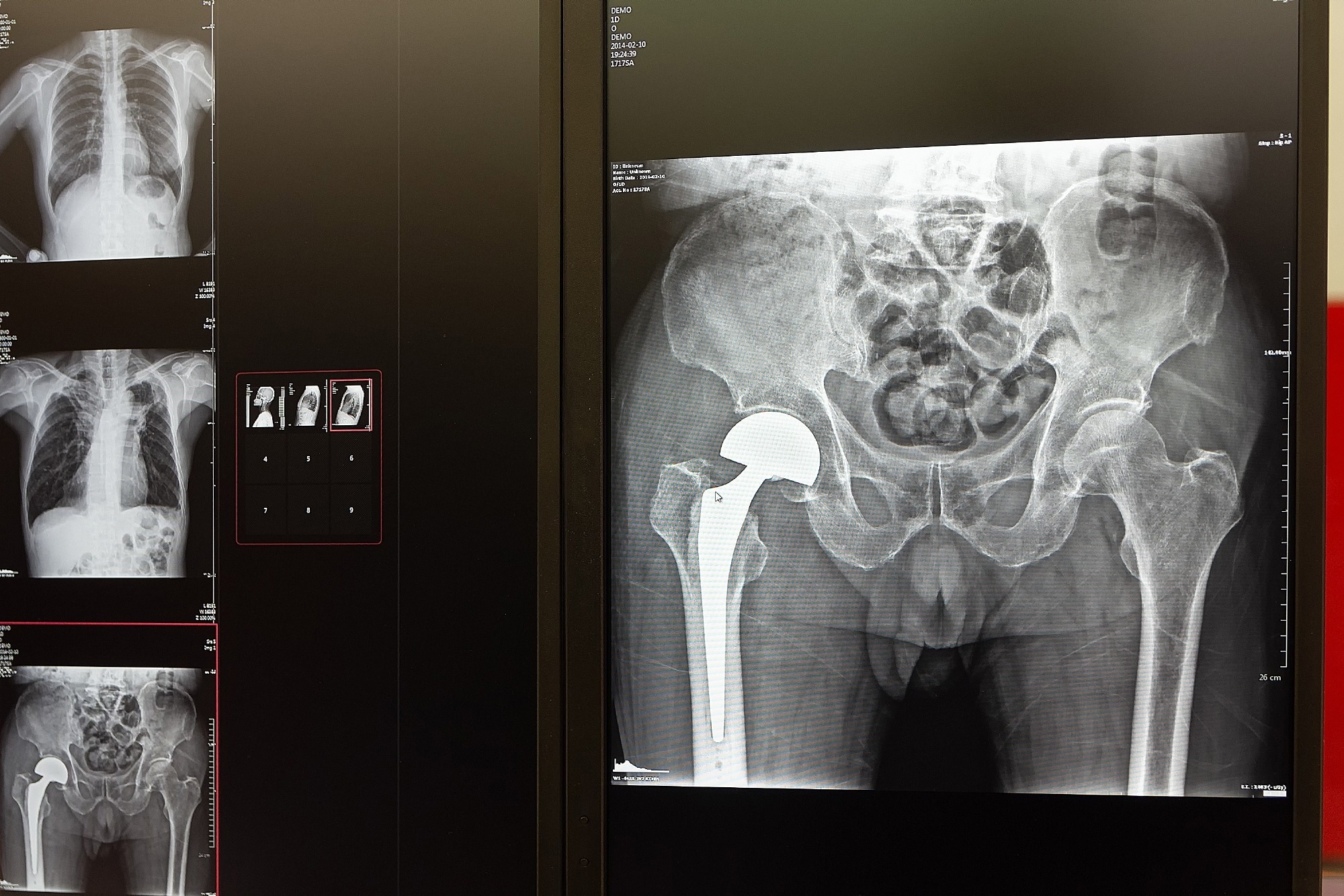

Walking speed before surgery predicts who thrives after hip replacement

A simple 10-meter walking test before surgery may help clinicians and patients identify the optimal timing for hip replacement and set realistic expectations for recovery.

Study: Preoperative Gait Speed as a Predictor of…

Continue Reading

Thousands of patients in England at risk as GP referrals vanish into NHS ‘black hole’ | GPs

One in seven people in England who need hospital care are not receiving it because their GP referral is lost, rejected or delayed, the NHS’s patient watchdog has found.

Three-quarters (75%) of those trapped in this “referrals black hole”…

Continue Reading

Early exposure to fat-related food smells increases lifelong obesity risk

New experimental evidence shows that food smells encountered before birth and during early life can rewire brain and metabolic responses to fat, increasing the risk of obesity later in life, even in the absence of maternal obesity…

Continue Reading

Steep Rise in Flu Infections Across Israel, Pandemic Response Team to Meet

The early December weather this year in no way resembles a real winter, but when it comes to seasonal illnesses, the season has already arrived in full force. Over the past few weeks, the incidence of flu and other winter viral respiratory…

Continue Reading