- World AIDS Day report 2025: Overcoming disruption, transforming the AIDS response ReliefWeb

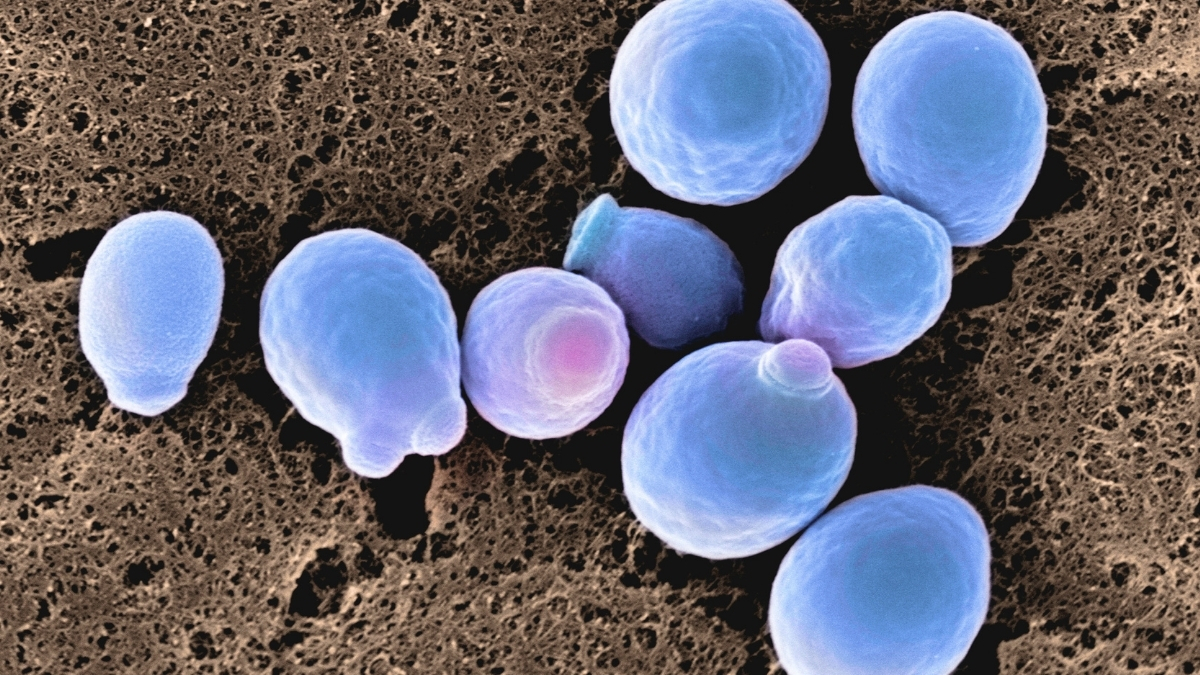

- Aid cuts have shaken HIV/Aids care to its core – and will mean millions more infections ahead The Guardian

- New prevention tools and investment in…

- Oral corticosteroids are increasingly used…