- New Molecule Blocks Deadliest Brain Cancer at Its Genetic Root SciTechDaily

- This Deadly Brain Cancer Currently Has No Cure. Scientists Just Found A Way To Kill It IFLScience

- Brown University Health researchers identify new target for glioblastoma…

Category: 6. Health

-

New Molecule Blocks Deadliest Brain Cancer at Its Genetic Root – SciTechDaily

-

AI reads brain MRIs in seconds and flags emergencies

A newly developed artificial intelligence system from the University of Michigan can analyze brain MRI scans and deliver a diagnosis in a matter of seconds, according to a new study. The model identified neurological conditions with accuracy…

Continue Reading

-

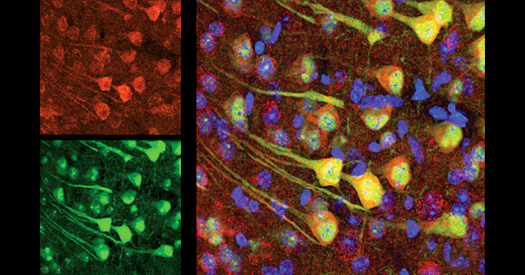

Aging neurons outsource garbage disposal, clog microglia

Synaptic proteins degrade more slowly in aged mice than in younger mice, a new study finds. Microglia appear to unburden the neurons of the excess proteins, but that accumulation may turn toxic, the findings suggest.

To function…

Continue Reading

-

Do men and women face the same mental health challenges? – Deseret News

- Significant differences exist in mental health crisis symptoms for men and women.

- In men and boys, a crisis may be interpreted as simply problem behavior.

- Reducing stigma opens up helpful discussions about mental health.

For years, women died of…

Continue Reading

-

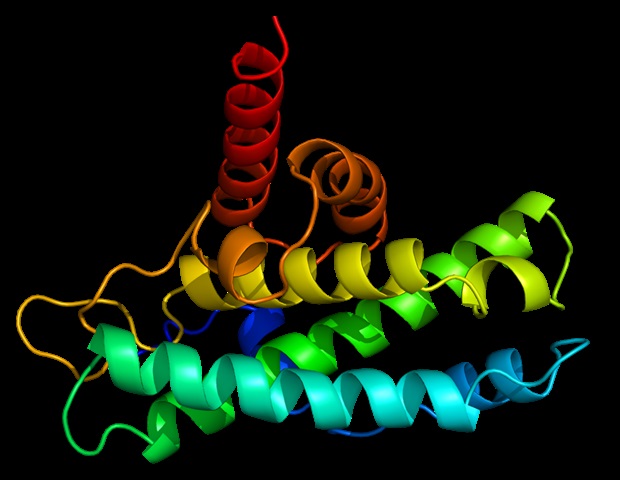

Newly identified protein interaction fine-tunes cellular stress responses

Cornell researchers have discovered a new way cells regulate how they respond to stress, identifying an interaction between two proteins that helps keep a critical cellular recycling system in balance.

The findings show that a…

Continue Reading

-

Bird Owners Warned to Remain Vigilant Against Psittacosis – Kiripost

- Bird Owners Warned to Remain Vigilant Against Psittacosis Kiripost

- Public Advised on Bird-Transmitted Disease Psittacosis Prevention Cambodianess

- Thailand confirms first parrot fever case and urges caution among bird owners The Star | Malaysia

Continue Reading

-

‘Protein factories’ linked to age-related infertility

Researchers at Nankai University in Tianjin have identified a breakthrough biological target for treating age-related infertility.

The study, published in Cell Reports Medicine, offers a fresh perspective on why…

Continue Reading

-

Medical misinformation more likely to fool AI if source appears legitimate, study shows

Feb 9 : Artificial intelligence tools are more likely to provide incorrect medical advice when the misinformation comes from what the software considers to be an authoritative source, a new study found.

In tests of 20 open-source and proprietary…

Continue Reading

-

Statin Adverse Event Labels May Be Overcautious, Analysis Suggests – MedPage Today

- Statin Adverse Event Labels May Be Overcautious, Analysis Suggests MedPage Today

- The truth about statins and memory and dementia The Telegraph

- Most statin side effects are not backed by trials News-Medical

- Statin Drugs Are Safer Than Warnings…

Continue Reading

-

Triazoles vs Liposomal Amphotericin B Show Similar Survival in Invasive Aspergillosis Study

Invasive aspergillosis (IA) remains a serious and often fatal infection despite advances in diagnostics and antifungal therapy. Although mold-active triazoles have long been recommended as first-line therapy, liposomal amphotericin B continues…

Continue Reading