Category: 6. Health

-

Subjective slow walking speed is associated with locomotive syndrome severity in 34,935 adults undergoing medical checkups

Ohe, T. The history of locomotive syndrome-3. Japanese Orthop. Association (JOA). 122, 6 (2020). (In Japanese).

Nakamura, K. & Ogata, T. Locomotive syndrome: definition and management. Clin….

Continue Reading

-

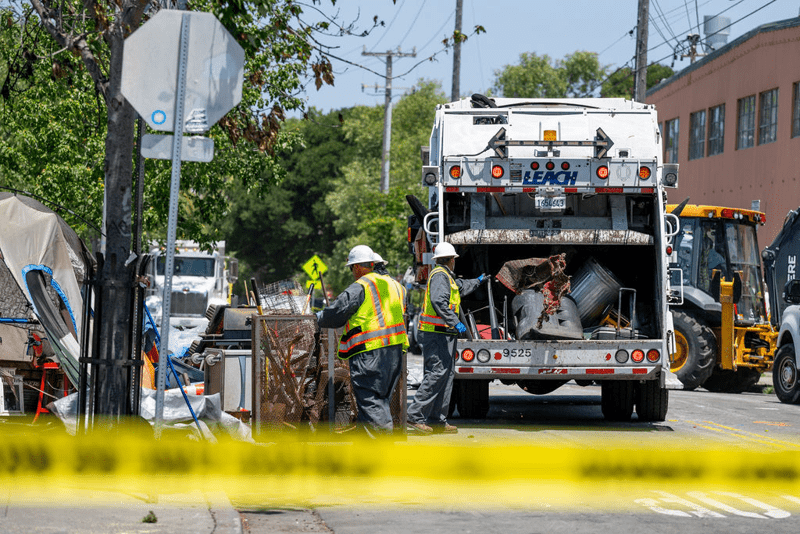

Leptospirosis found in dogs, rats near Northwest Berkeley camp

City workers remove tents and other belongings during an operation to clear the camp last June. Credit: Adahlia Cole for Berkeleyside Berkeley’s public health officer says people and pets in Northwest Berkeley are at risk from an…

Continue Reading

-

FREE 15-Minute Rapid HIV & Hepatitis STD Screening – Naples – Florida Department of Health in Collier County (.gov)

- FREE 15-Minute Rapid HIV & Hepatitis STD Screening – Naples Florida Department of Health in Collier County (.gov)

- FREE 15-MINUTE RAPID HIV AND HEPATITIS STD SCREENING (Copy) Florida Department of Health in Collier County (.gov)

- FREE 15-Minute…

Continue Reading

-

expert reaction to small, achievable changes in physical activity linked to lower mortality risks

A study published in The Lancet looks at small changes in physical activity and mortality risk.

Dr Richard…

Continue Reading

-

Five minutes more exercise and 30 minutes less sitting could help millions live longer | Health

Just five extra minutes of exercise and half an hour less sitting time each day could help millions of people live longer, according to research highlighting the potentially huge population benefits of making even tiny lifestyle changes.

Until…

Continue Reading

-

Journal of Medical Internet Research

Introduction

Hypertension is a major public health concern with an enormous economic and social burden []. The World Health Statistics 2023 report by the World Health Organization (WHO) states that the worldwide prevalence of hypertension reached…

Continue Reading

-

Community pharmacy cholesterol testing pilot expands across east London – The Pharmaceutical Journal

- Community pharmacy cholesterol testing pilot expands across east London The Pharmaceutical Journal

- Seventy London pharmacies to offer free cholesterol tests thepharmacist.co.uk

- 70 more pharmacies to provide cholesterol test results in 7 minutes

Continue Reading

-

A Conversation, Not a Conclusion

Join us for a public webinar on Social Health and Digital Play: A Conversation, Not a Conclusion where we aim to share insights from WHO’s work on social connection; reflect on the current state of the evidence on how video gameplay may…

Continue Reading

-

LGB+ people in England and Wales ‘much’ more likely to die by suicide than straight people | Mental health

LGB+ people are much more likely to die by taking their own lives, drug overdoses and alcohol-related disease than their straight counterparts, the first official figures of their kind show.

The 2021 census in England and Wales asked people aged…

Continue Reading