Chan JF, Yuan S, Kok KH, To KK, Chu H, Yang J, et al. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):514–23.

Category: 6. Health

-

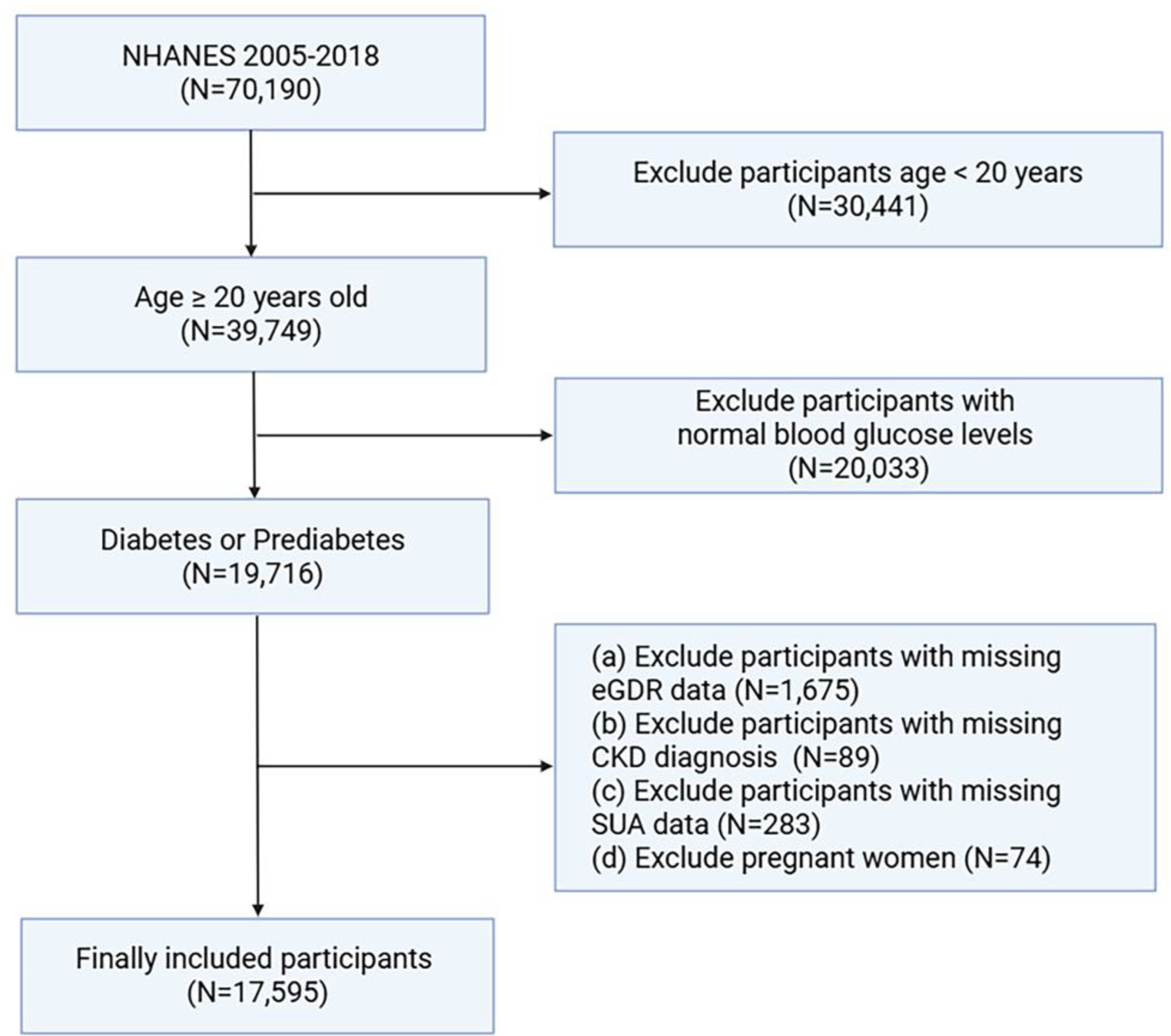

Serum uric acid mediates the association between the estimated glucose disposal rate and chronic kidney disease in patients with diabetes or prediabetes: an analysis from NHANES 2005–2018 | BMC Endocrine Disorders

Sun H, Saeedi P, Karuranga S, Pinkepank M, Ogurtsova K, Duncan B B, et al. IDF diabetes atlas: global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2022;183:109119.

Continue Reading

-

Just a moment…

Just a moment… This request seems a bit unusual, so we need to confirm that you’re human. Please press and hold the button until it turns completely green. Thank you for your cooperation!

Continue Reading

-

Breakthroughs Can’t Wait: Can Exercise Help Breast Cancer Patients During Chemotherapy?

Breakthroughs Can’t Wait: Can Exercise Help Breast Cancer Patients During Chemotherapy?

November 12, 2025

…Continue Reading

-

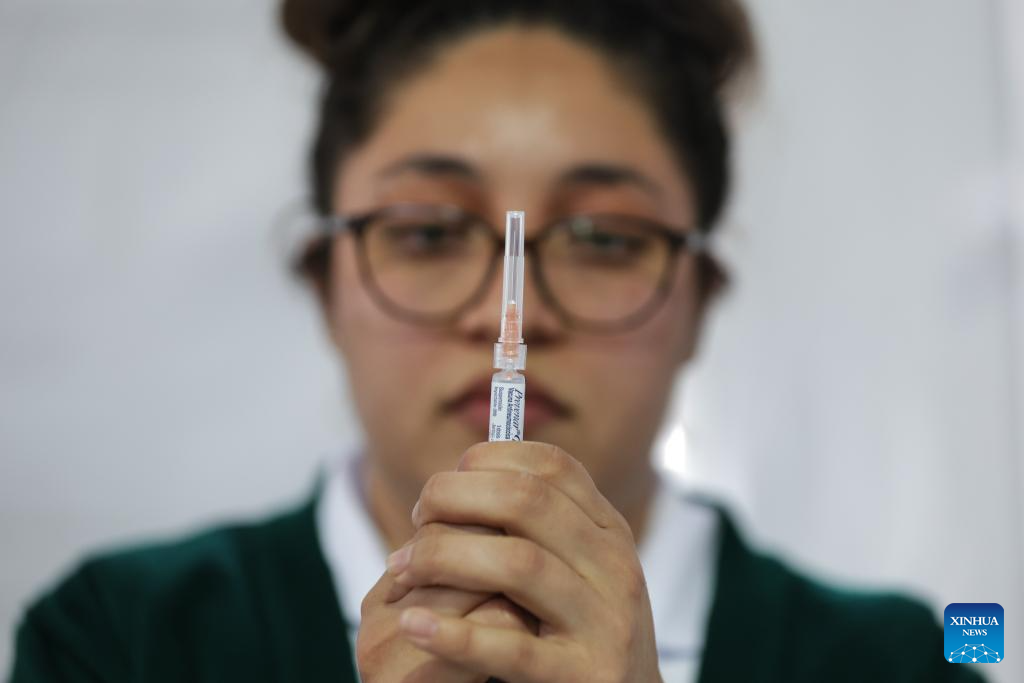

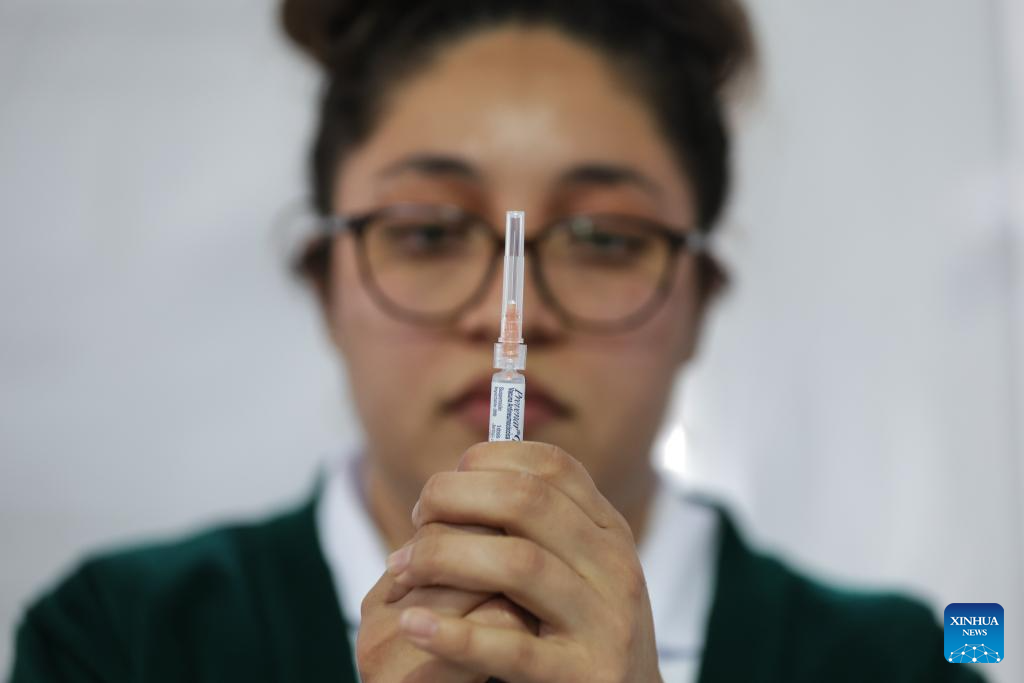

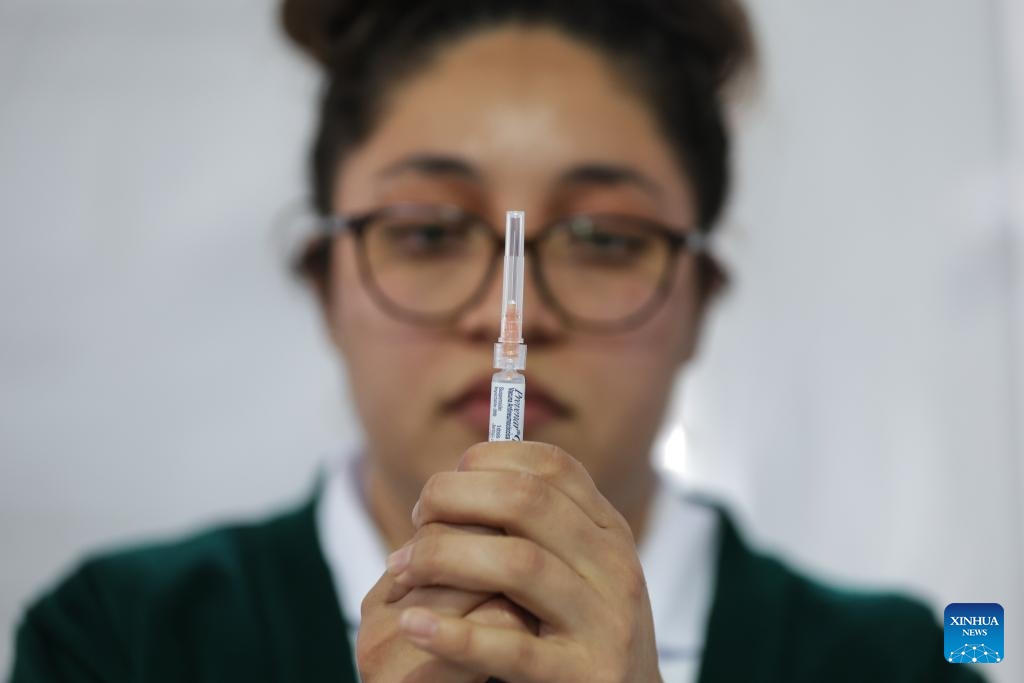

Mexico City takes measures to improve community immunization coverage during winter season-Xinhua

A health worker prepares to administer a vaccine at a vaccination center in Mexico City, capital of Mexico, Nov. 12, 2025. Mexico City has set up a vaccination center offering influenza, COVID-19, pneumococcal and measles vaccines to the public…

Continue Reading

-

Mexico City takes measures to improve community immunization coverage during winter season-Xinhua

A health worker prepares to administer a vaccine at a vaccination center in Mexico City, capital of Mexico, Nov. 12, 2025. Mexico City has set up a vaccination center offering influenza, COVID-19, pneumococcal and measles vaccines to the public…

Continue Reading

-

Mexico City takes measures to improve community immunization coverage during winter season-Xinhua

A health worker prepares to administer a vaccine at a vaccination center in Mexico City, capital of Mexico, Nov. 12, 2025. Mexico City has set up a vaccination center offering influenza, COVID-19, pneumococcal and measles vaccines to the public…

Continue Reading

-

Early lean mass shapes long-term brain development in preterm infants

A new study reveals that the quality of early growth, not just weight gain, influences long-term brain outcomes for extremely preterm infants, highlighting fat-free mass as a crucial marker of early developmental health.

Study:

Continue Reading

-

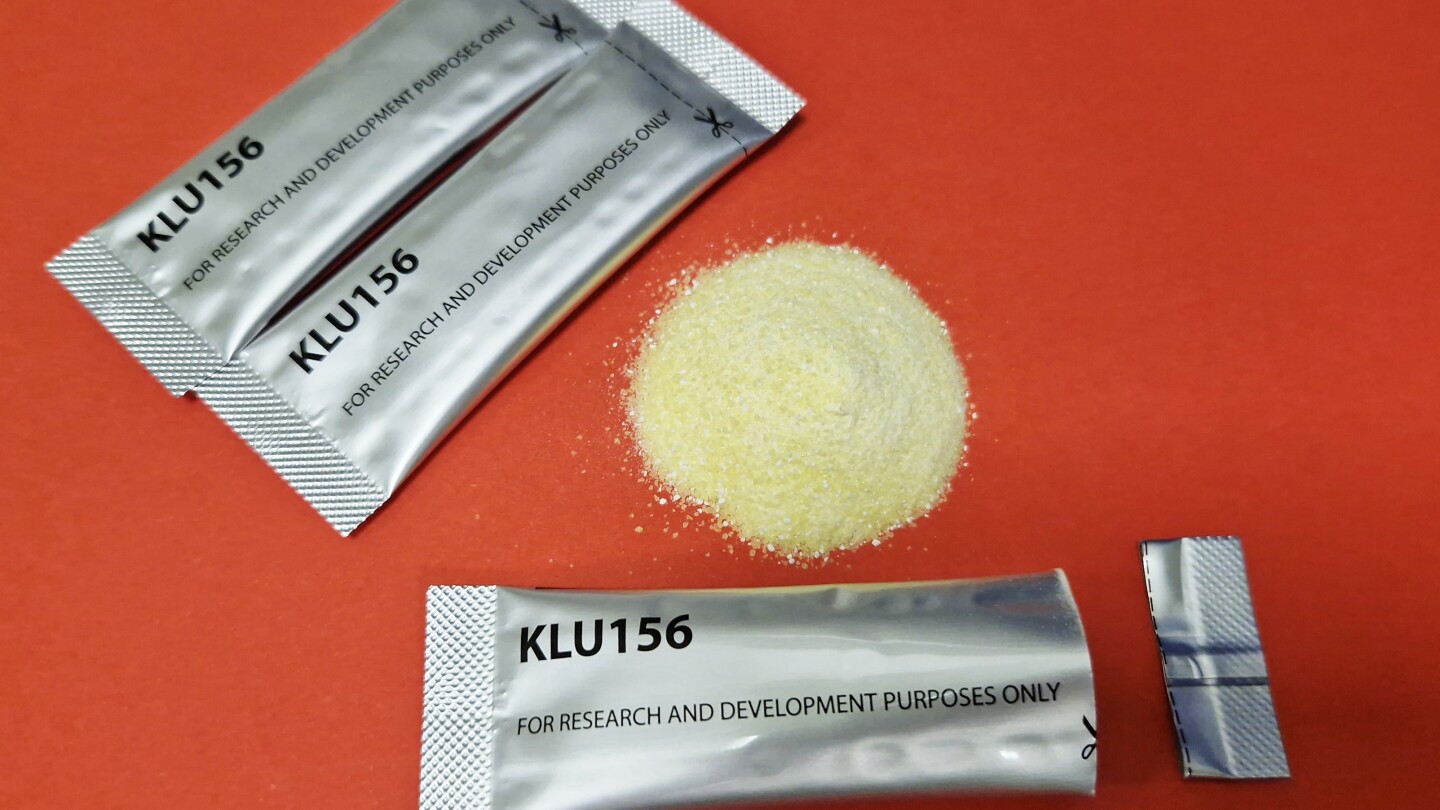

New malaria treatments show promise as drug resistance grows

NEW YORK (AP) — Researchers on Wednesday reported two promising new approaches to counteract malaria’s growing resistance to medication — one involving a new class of drugs.

Switzerland-based Novartis…

Continue Reading