- World Pneumonia Day being observed today. RADIO PAKISTAN

- World Pneumonia Day – 12 November 2025 World Health Organization (WHO)

- MyVoice: Views of our readers 12th Nov 2025 The Hans India

- World Pneumonia Day: 7 Warning Signs of Pneumonia You…

Category: 6. Health

-

World Pneumonia Day being observed today. – RADIO PAKISTAN

-

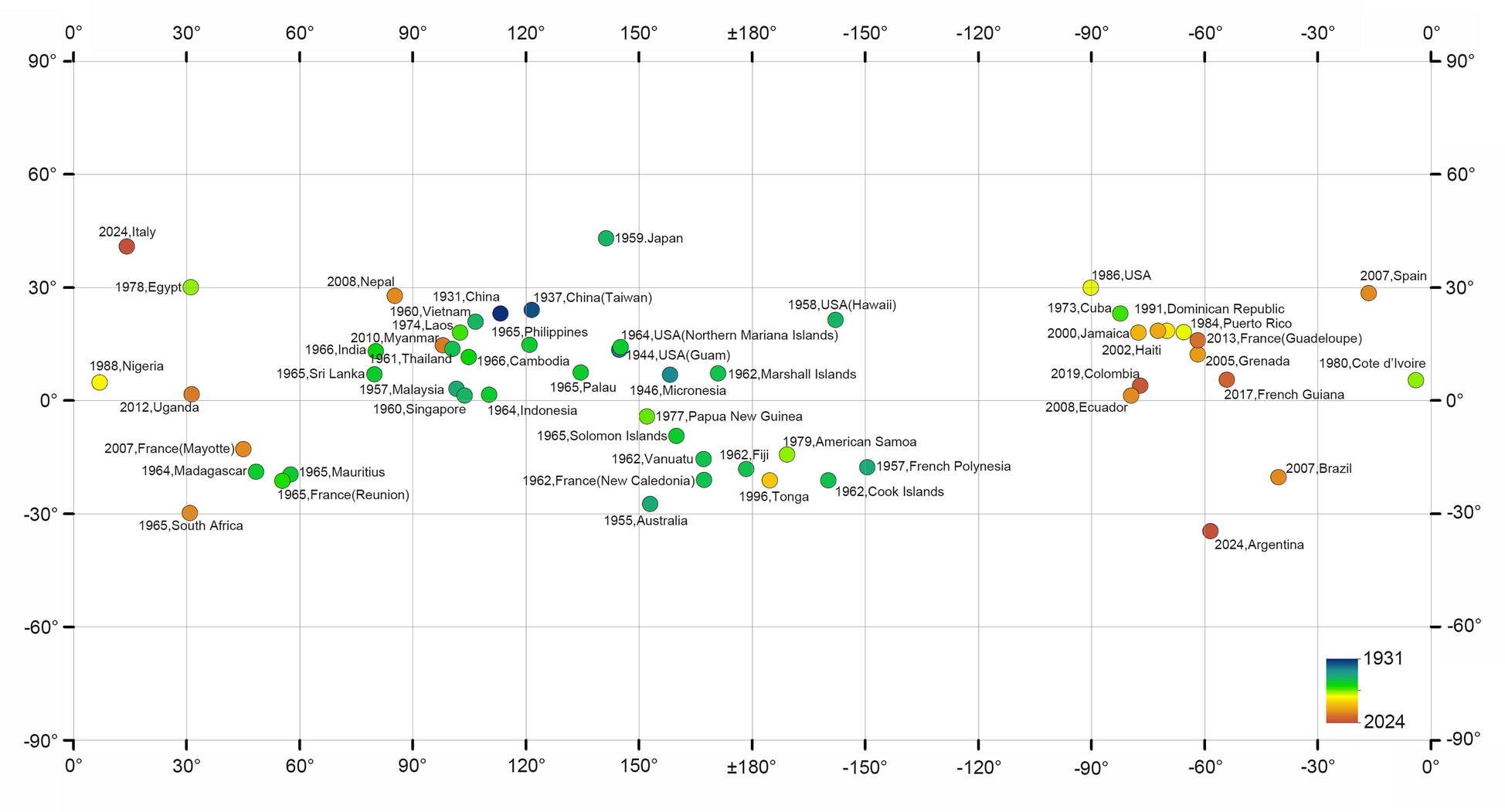

The 90th anniversary of Angiostrongylus cantonensis: from local discovery to global endemic | Infectious Diseases of Poverty

China’s history with A. cantonensis serves as a powerful microcosm of the global challenge posed by this emerging zoonosis. The country’s experience, marked by initial cases, devastating outbreaks, and the development of a robust national…

Continue Reading

-

Hepatologist shares which foods and drinks you should restrict, completely avoid or consume to reduce fatty liver risk

The World Health Organisation (WHO) data published on Sciencedirect.com in April 2024 shows the growing burden of liver disease globally, with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and alcohol-related liver disease being major contributors….

Continue Reading

-

Integrating transcriptome and metabolome reveals sex-dependent meat quality regulation in Qiandongnan Xiaoxiang chickens | BMC Genomics

Wooszyk J, Haraf G, Okruszek A, Wereńska M, Teleszko M. Fatty acid profiles and health lipid indices in the breast muscles of local Polish Goose varieties. Poult Sci. 2020;99:1216–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psj.2019.10.026.

Continue Reading

-

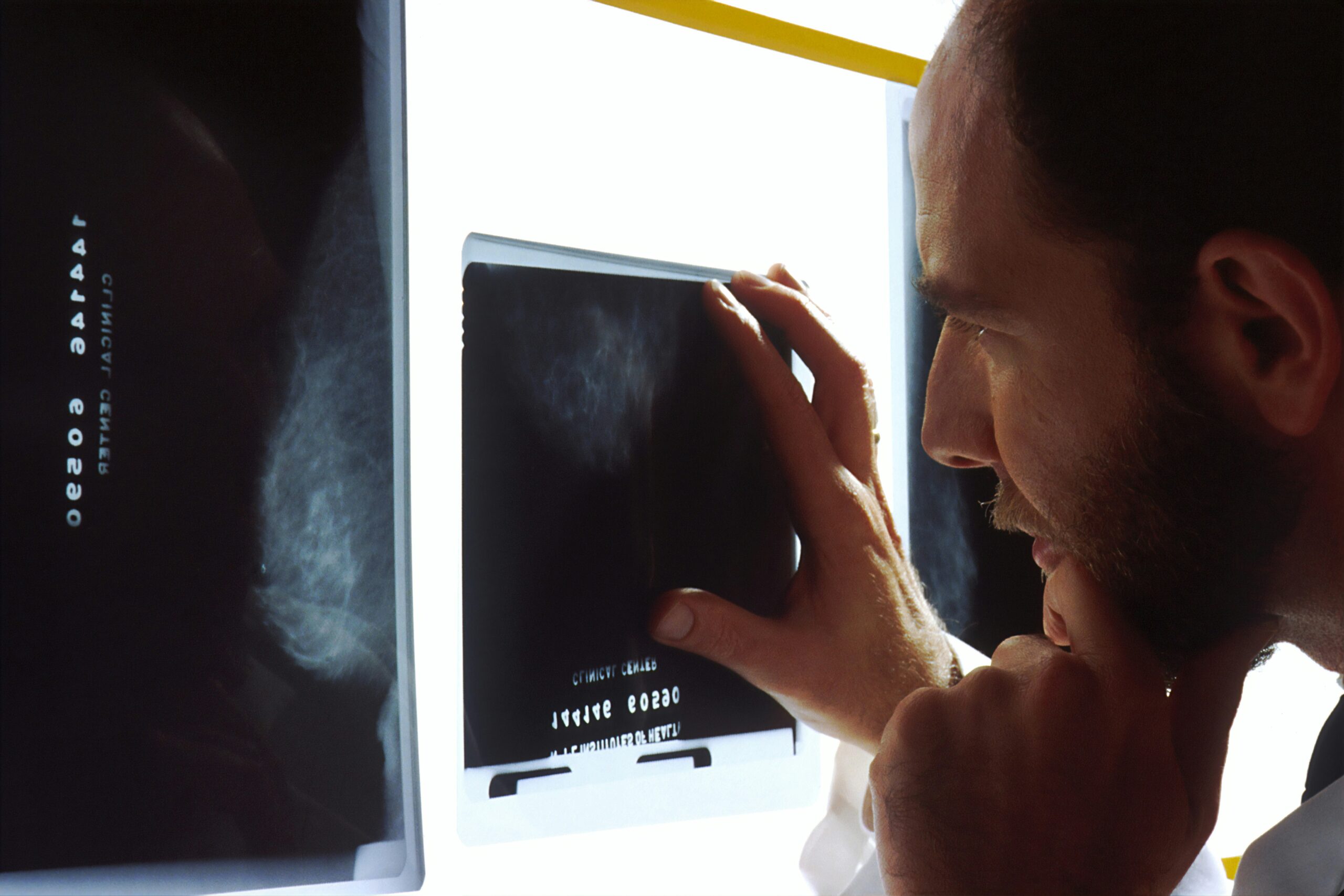

Can GLP-1 Drugs Protect Against Lung Cancer in T2D? – Medscape

- Can GLP-1 Drugs Protect Against Lung Cancer in T2D? Medscape

- GLP-1 Drugs Linked to Dramatically Lower Death Rates in Colon Cancer Patients UC San Diego Today

- Use of Obesity Drugs in Cancer Patients Increases Despite Lack of Clinical Guidance

Continue Reading

-

Lung protection: Preventing pneumonia in the young and elderly – news.cgtn.com

- Lung protection: Preventing pneumonia in the young and elderly news.cgtn.com

- World Pneumonia Day – 12 November 2025 World Health Organization (WHO)

- MyVoice: Views of our readers 12th Nov 2025 The Hans India

- Doctors urge parents to prioritise…

Continue Reading

-

‘There are safe, simple steps that parents can take’

One thing all parents can agree on is that they want their children to stay safe and grow up to be healthy adults.

Research has concluded that early exposure to plastic can be detrimental to children’s health.

What’s happening?

A review published in…

Continue Reading

-

Antibiotic Repurposing Targets CNS Tuberculosis: NUS Study

Researchers at the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore (NUS Medicine), have demonstrated that doxycycline, a commonly available and inexpensive antibiotic, can improve survival rates and neurological…

Continue Reading

-

What diet do people with type 2 diabetes really want? Study reveals flexibility beats strict meal plans

British adults with diabetes overwhelmingly favor simple, adaptable eating patterns over rigid low-calorie meal replacements, highlighting that personal choice may be key to long-term adherence and better health outcomes.

Study:

Continue Reading

-

Hormonal fluctuations shape learning through changes in dopamine signaling

Researchers have long established that hormones significantly affect the brain, creating changes in emotion, energy levels, and decision-making. However, the intricacies of these processes are not well understood.

A new study by a…

Continue Reading