We usually think of flu as the rapid spreader, while gut bacteria quietly sit in our intestines. But recent research shows that one strain of E. coli, known as ST131‑A, can move through populations at a rate comparable to flu viruses. This…

Category: 6. Health

-

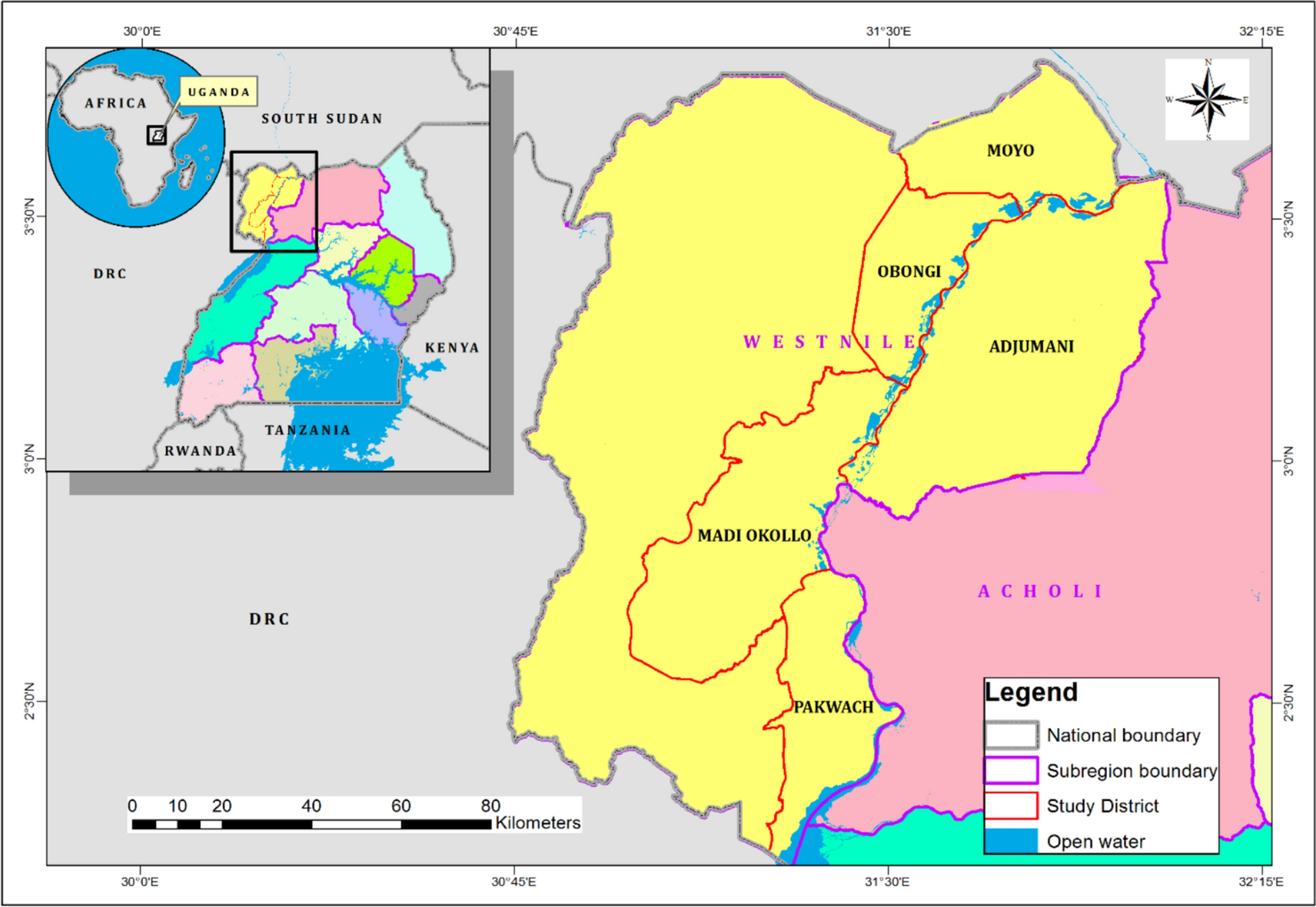

Indigenous knowledge and plant species used as mosquito repellents in the West Nile Subregion, Uganda | Tropical Medicine and Health

Documented plants with mosquito repellent properties

Although several plant species with insect-repelling properties exist in the tropics [21], they have mostly remained unexplored, with only a few studies documenting the medicinal plant species…

Continue Reading

-

Baseless claims target Bangladesh’s typhoid vaccine drive

“I would request parents, do not let enter your beloved child’s body at all. Stay away from these,” of a lengthy Bengali-language Facebook post shared on October 14, 2025.

The post, which was shared more than 3,000 times, goes on to say: “…

Continue Reading

-

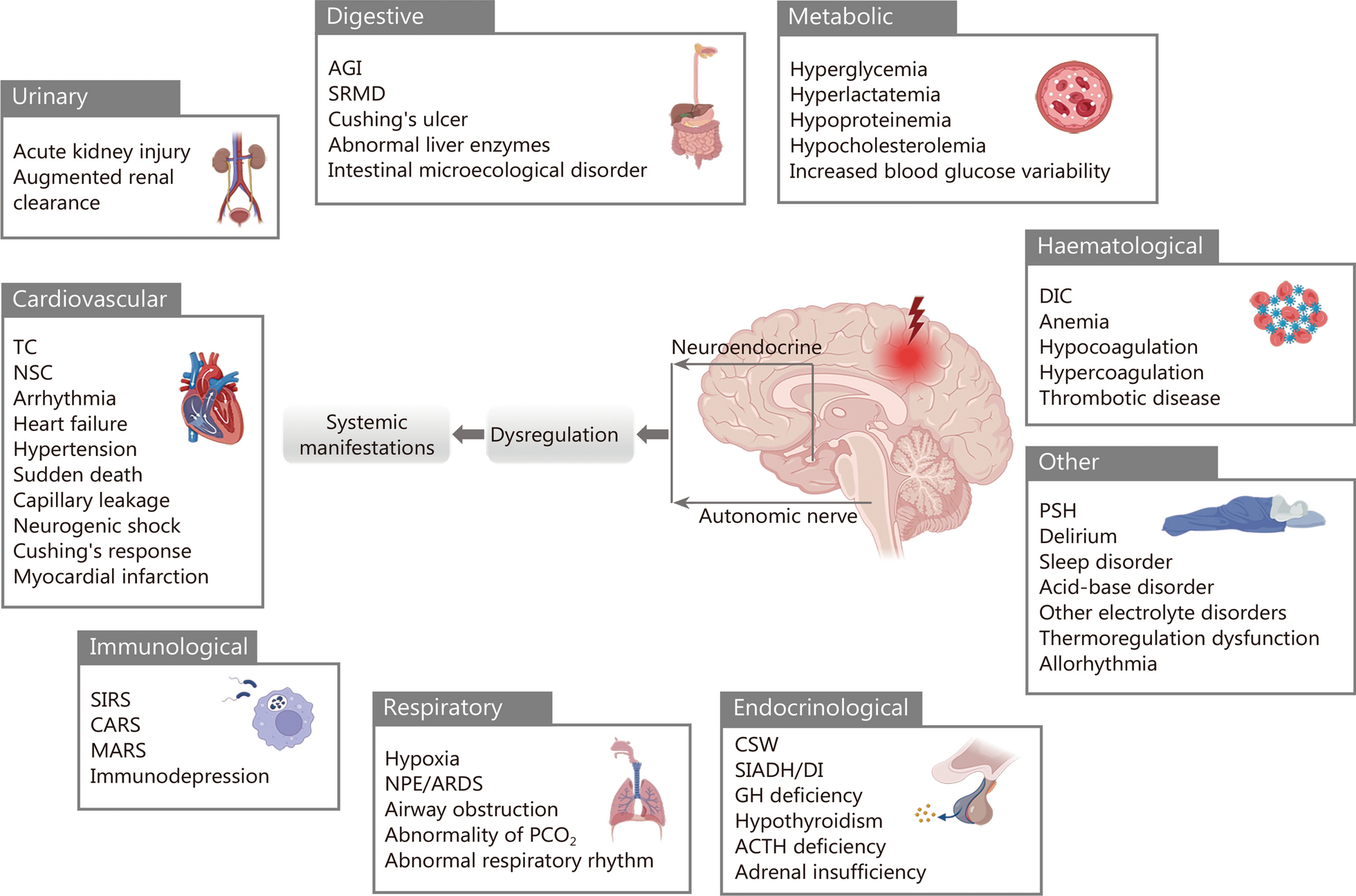

Neurogenic organ dysfunction syndrome after acute brain injury | Military Medical Research

GBD 2019 Stroke Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of stroke and its risk factors, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet Neurol. 2021;20(10):795–820.

Continue Reading

-

Jersey skin cancer rate ‘higher than Guernsey’

Non melanoma skin cancer (NMSC) is the most common type of cancer across the Channel Islands, according to a new report.

The Channel Islands Cancer Report also showed higher rates of skin cancer in Jersey than in Guernsey and England.

In both…

Continue Reading

-

From lupus to MS, new treatments aim to retrain immune system

Our immune system has a dark side: It’s supposed to fight off invaders to keep us healthy. But sometimes it turns traitor and attacks our own cells and tissues.

What are called autoimmune diseases can affect just about…

Continue Reading

-

GPs Urged to Lead ADHD Reform in the NHS – Medscape

- GPs Urged to Lead ADHD Reform in the NHS Medscape

- ADHD Crisis Grows In England As Services Limit Access Evrim Ağacı

- NHS Confederation responds to ADHD Taskforce final report NHS Confederation

- Taskforce recommends more training in ADHD for…

Continue Reading

-

EXCLUSIVE: US Ties Global Health Aid To Data Sharing On Pathogens – Undermining WHO Talks

Luyengo Clinic in Eswatini. PEPFAR funded 80% of the clinic’s cost, but the HIV treatment of 3,000 people has been under threat since the US suspended aid in January. The United States (US) aims to compel countries that receive its aid to…

Continue Reading

-

The Best Anti-Inflammatory Breakfast for Healthy Aging

- Start your day with an anti-inflammatory breakfast like our Egg, Tomato & Feta Pita to support healthy aging.

- The dish offers nutrients like protein and fiber to preserve lean muscle mass and reduce inflammation as you age.

- This balanced meal…

Continue Reading