In Argentina’s Patagonia region 95 million years ago, some huge dinosaurs roamed the landscape, including fearsome meat-eater Giganotosaurus, at about eight tons, and immense long-necked plant-eater Argentinosaurus, perhaps 70 tons. But this…

Category: 7. Science

-

Sky to display rare 6-planet alignment forming ‘planetary parade’ on February 28

Sky to display rare 6-planet alignment forming ‘planetary parade’ on February 28 Six planets, including Mercury, Venus, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune, will align along the ecliptic this Saturday, February…

Continue Reading

-

Scientists Just Caught Trees Firing Off Ultraviolet Sparkles During Thunderstorms

In the summer of 2024, a team of researchers went storm-chasing in a Toyota Sienna minivan in search of tiny, faint sparks lighting up the tips of leaves. As a thunderstorm raged overhead, the researchers pointed their camera at…

Continue Reading

-

NCAR: New Research Takes 1st Step Toward Advance Warnings of Space Weather – HPCwire

- NCAR: New Research Takes 1st Step Toward Advance Warnings of Space Weather HPCwire

- New research takes first step toward advance warnings of space weather University Corporation for Atmospheric Research

- Surprise solar eruptions on sun’s far side…

Continue Reading

-

Tiny Vortices Reveal New Superconductivity Mechanism

Scientists are increasingly focused on understanding the unusual superconducting properties emerging in kagome materials, and a new theoretical study led by Frederik A. S. Philipsen and Mats Barkman, both from the Niels Bohr Institute,…

Continue Reading

-

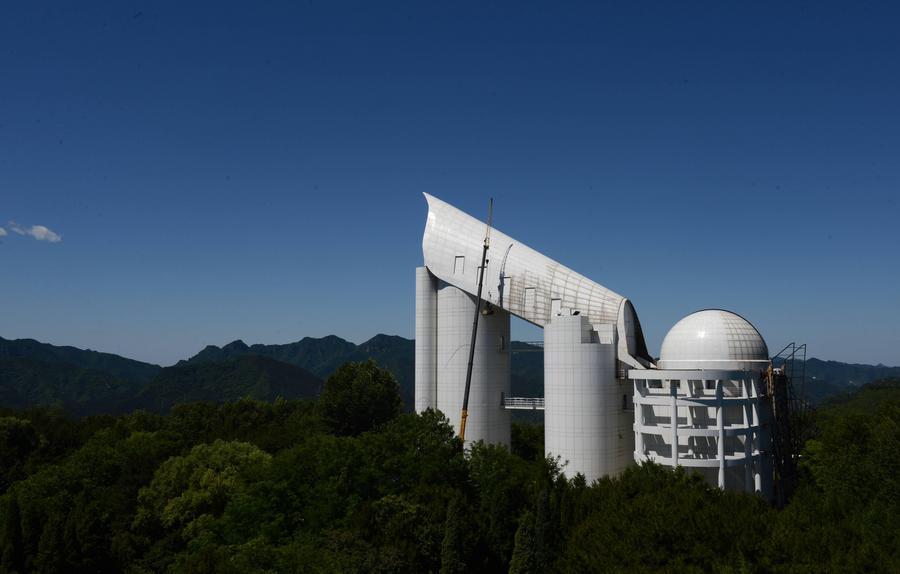

Chinese researchers develop AI model to process stellar data from different telescopes-Xinhua

Photo taken on June 19, 2015 shows the Large Sky Area Multi-Object Fibre Spectroscopy Telescope (LAMOST) at the Xinglong observation station of the National Astronomical Observatories under the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Xinglong, north… Continue Reading

-

AI Predicts Experiment Outcomes Using Game Theory

Scientists are exploring new avenues to reconcile quantum theory with classical physics by challenging fundamental assumptions about free choice in experiments. Florian Pauschitz from ETH Zurich, Ben Moseley from Imperial College, and Ghislain…

Continue Reading

-

NASA study finds ancient life could survive 50 million years in Martian ice

Future missions to Mars may want to dig into ice rather than rock. Scientists say ancient microbes, or traces of them, could be locked inside Martian ice deposits, preserved for tens of millions of years.

Researchers from NASA Goddard Space…

Continue Reading

-

What’s behind the evolution of Earth’s deep interior?

According to a new study, researchers have…

Continue Reading