How can researchers best frame the impact of their work to make sure its significance is recognised? What skills do today’s scientists need to develop to thrive in the decade ahead?

RSC Applied Interfaces associate editor Ryan Richards…

How can researchers best frame the impact of their work to make sure its significance is recognised? What skills do today’s scientists need to develop to thrive in the decade ahead?

RSC Applied Interfaces associate editor Ryan Richards…

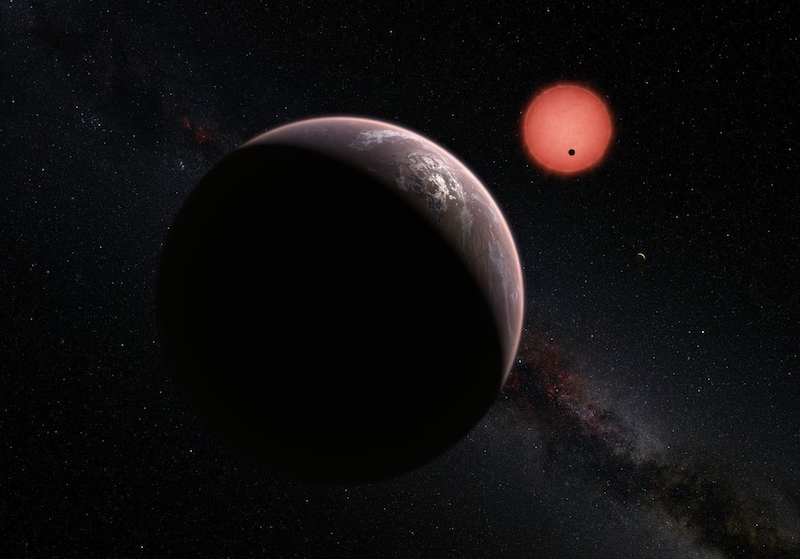

If you read enough articles about planets in binary star systems, you’ll realize almost all of them make some sort of reference to Tatooine, the fictional home of Luke Skywalker (and Darth Vader) in the Star War saga. Since that…

At least half of the world’s glaciers are expected to disappear by the end of the century due to climate change, according to a new study by Swiss researchers published Monday in the journal Nature Climate Change.

The study warns that between…

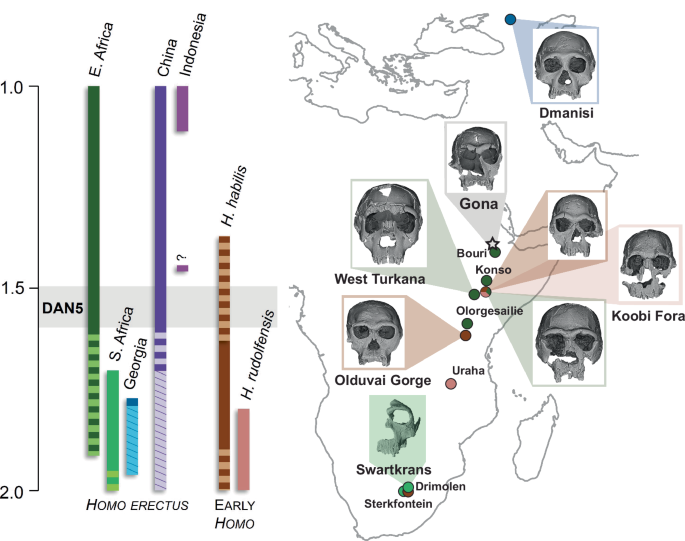

Kimbel, W. H., Johanson, D. C. & Rak, Y. Systematic assessment of a maxilla of Homo from Hadar, Ethiopia. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 103, 235–262 (1997).

Google Scholar

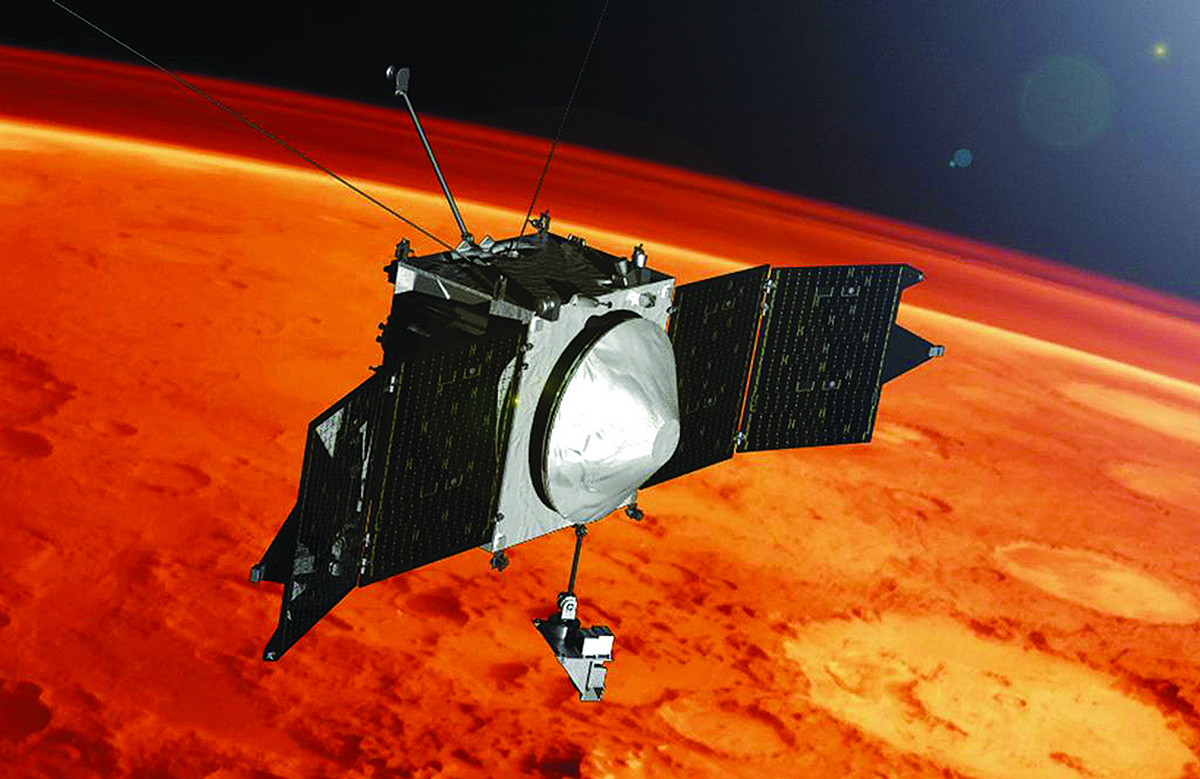

WASHINGTON — New analysis suggests that problems with NASA’s MAVEN Mars orbiter may be more serious than a simple communications glitch.

NASA said Dec. 9 that it lost contact with the spacecraft three days earlier after MAVEN failed…

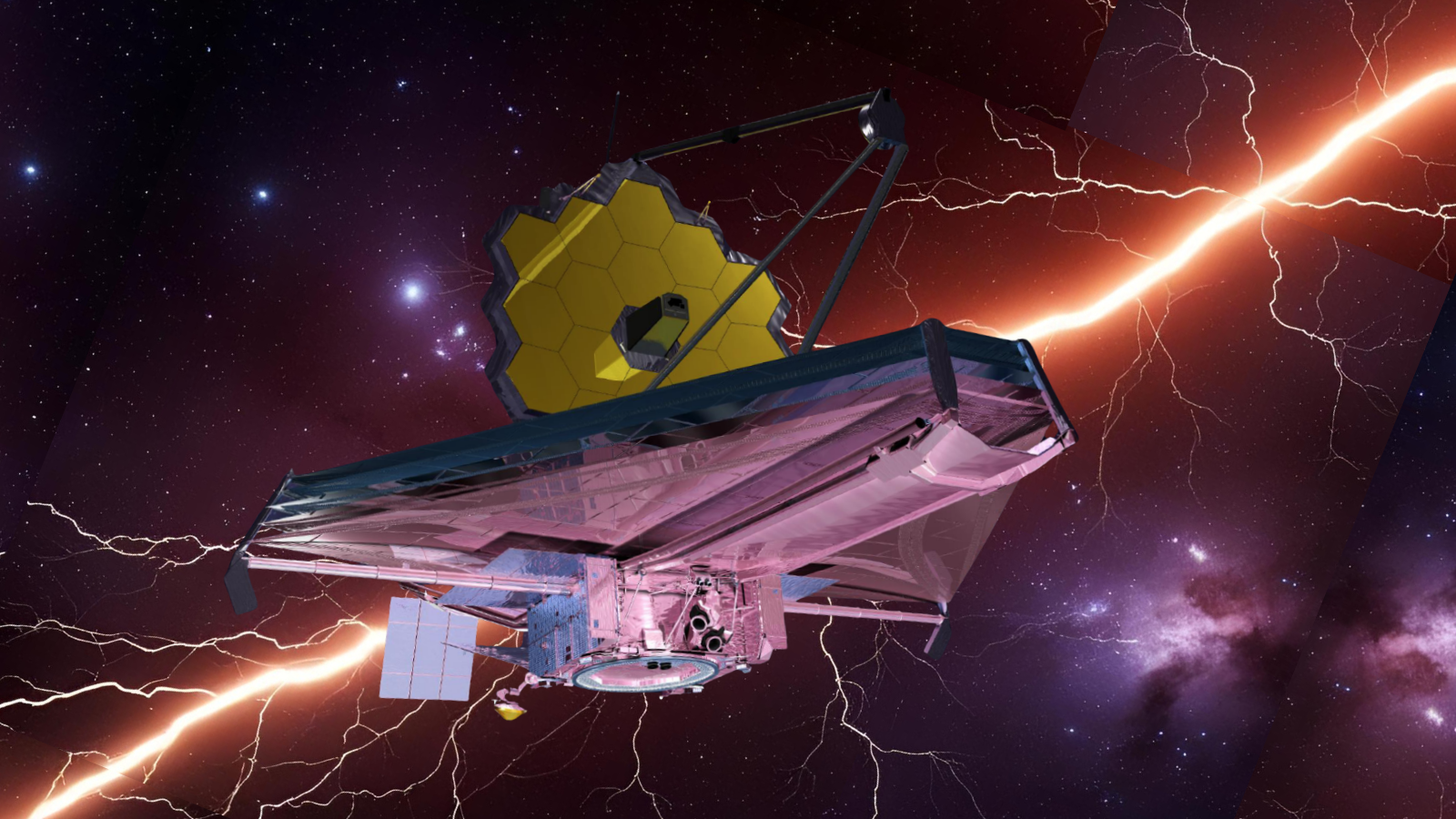

Since it began operations in 2022, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has allowed scientists to make incredible strides in our understanding of the cosmos — especially its early epoch. However, one lingering cosmological mystery that the…

A new mesoporous polymer combines optical transparency higher than glass with thermal conductivity lower than air. The material, which is easily made at the square-metre scale and should last decades, could be used to make insulating windows for…