“The Clairvoyant”

That man had a beautiful, exotic name—Leo. And that’s what he looked like too, like a lion.

He had let his hair and beard grow long, and one harsh winter they’d both gone gray, God knows why.

Leo the…

“The Clairvoyant”

That man had a beautiful, exotic name—Leo. And that’s what he looked like too, like a lion.

He had let his hair and beard grow long, and one harsh winter they’d both gone gray, God knows why.

Leo the…

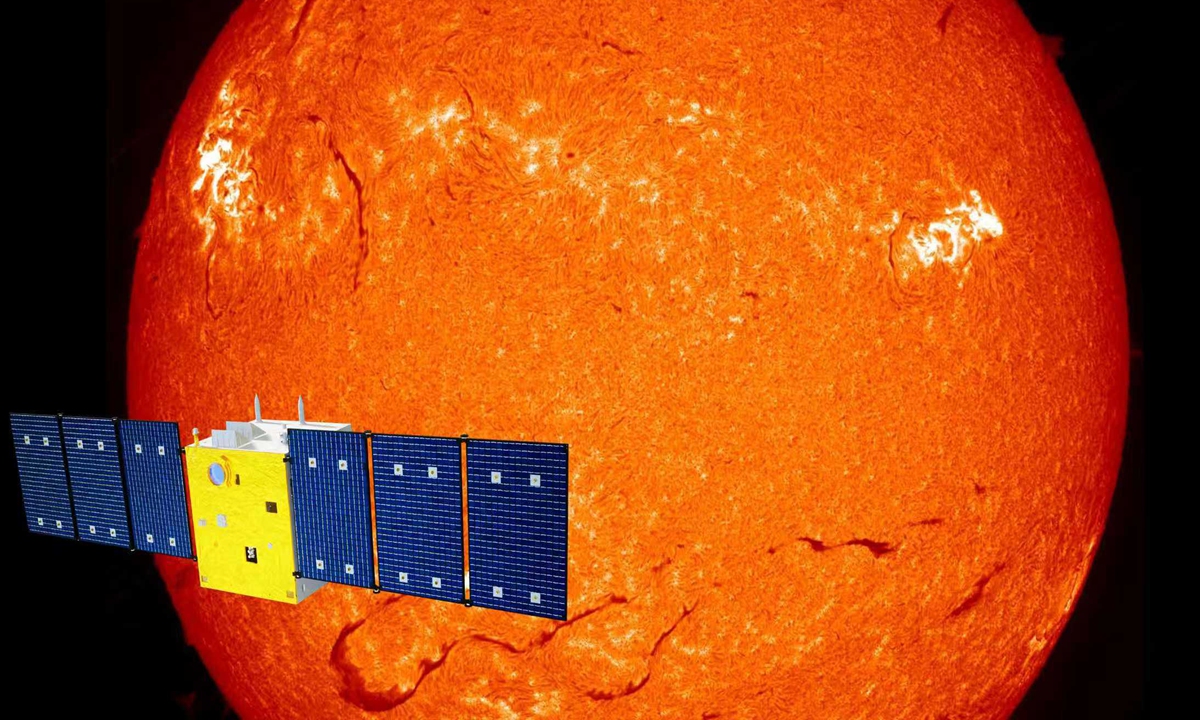

Illustration: Xihe sun exploration satellite

“With the help of the Xihe satellite, we can obtain full-disk solar spectra at more than 300 wavelength points simultaneously every 46 seconds. Each wavelength corresponds to different layers of the…

The lovely double star 145 Canis Majoris near the tail of the Big Dog offers stunning contrasting colors through binoculars or a telescope.

Canis…

For this new ESA/Webb Picture of the Month, the NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope has spied a pair of dwarf galaxies engaged in a gravitational dance. These two galaxies are named NGC 4490 and NGC 4485, and they’re located about…

Leimann, B. C., Monteiro, P. C., Lazéra, M., Candanoza, E. R. & Wanke, B. Protothecosis. Medical mycology 42, 95–106, https://doi.org/10.1080/13695780310001653653 (2004).

Kwiecinski, J….

The 2025 Antarctic ozone hole was the smallest and shortest-lived for five years, the Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (CAMS) has said, fuelling hopes for the recovery of the ozone layer.

The Antarctic ozone hole, which is shaped…

SpaceX has now launched 60 missions from California this year.

A Falcon 9 rocket lifted off Tuesday (Dec. 2) from Vandenberg Space Force Base on the Golden State’s central coast at 12:28 a.m. EST (0528 GMT; 9:28 p.m. local California time on Dec….

QUICK FACTS

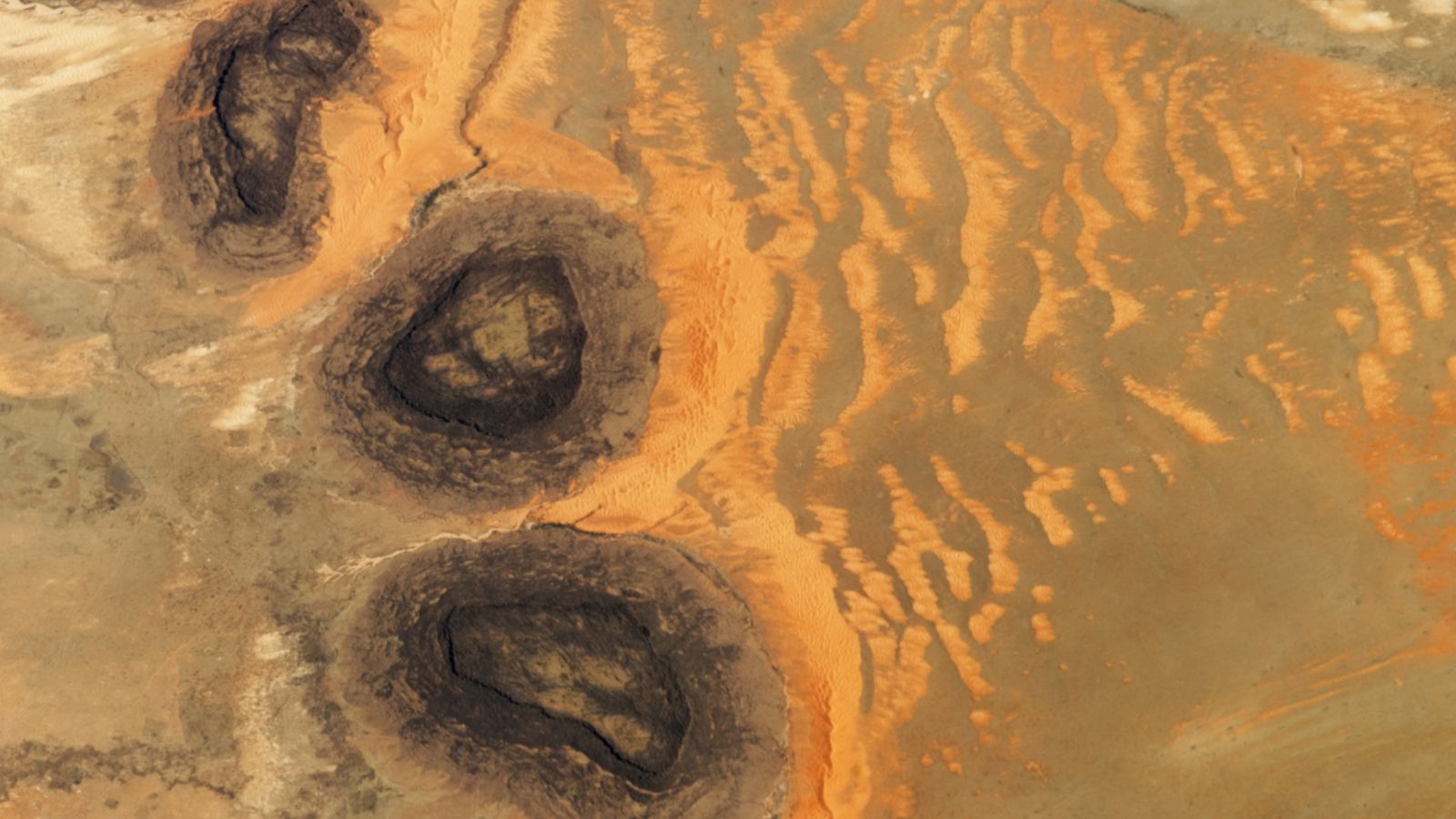

Where is it? Guérou, Mauritania [16.930575400, -11.759622605]

What’s in the photo? Three black mesas surrounded by unusual sand dunes in the Sahara Desert

Who took the photo? An unnamed astronaut onboard the International Space Station…

During the warm months, Lake Erie becomes an ideal setting for cyanobacteria, also known as blue-green algae, to grow rapidly. Under these conditions, the algae can form large blooms that release toxins at levels capable of harming both wildlife…