Join us tomorrow, Nov. 20, for Astronomy Unlocked, a virtual event focused on choosing your best telescope, complete with insight and tips from leading industry experts.

Category: 7. Science

-

The Gulf of Suez Rift Between Asia And Africa Is Being Pulled Apart By Half A Millimeter Each Year

Parts of the tectonic boundary between Africa and Asia may be creeping away from each other, as fresh evidence shows that a rift near the border of the two continents is slowly pulling apart at the pace of a very, very slow snail.

The rest of…

Continue Reading

-

NASA set to release new images of interstellar object 3I/ATLAS – Reuters

- NASA set to release new images of interstellar object 3I/ATLAS Reuters

- NASA to Share Comet 3I/ATLAS Images From Spacecraft, Telescopes NASA (.gov)

- Watch interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS speed away from the sun in free telescope livestream tonight

Continue Reading

-

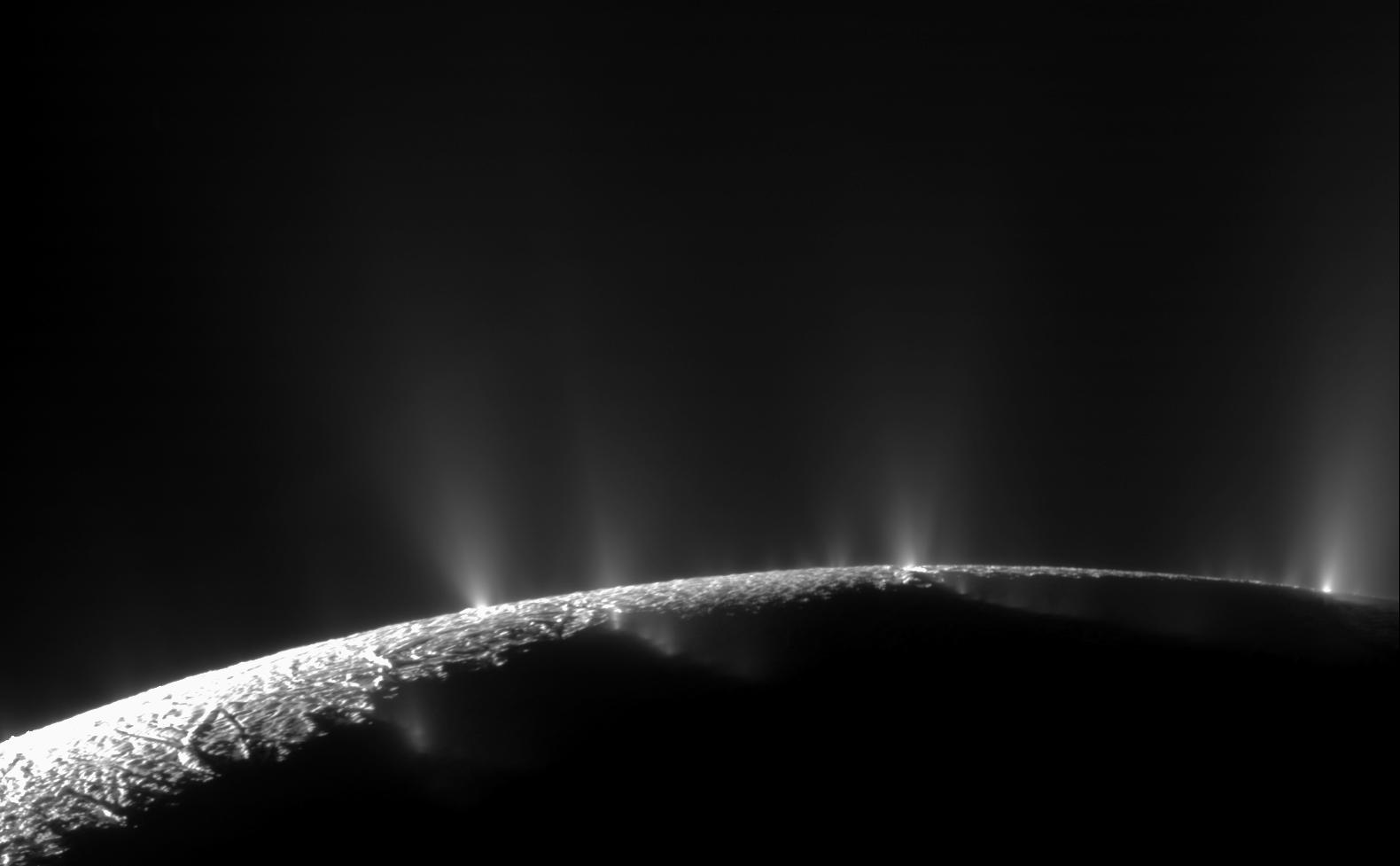

NASA Cassini Study Finds Organics ‘Fresh’ From Ocean of Enceladus

Researchers dove deep into information gathered from the ice grains that were collected during a close and super-fast flyby through a plume of Saturn’s icy moon.

A new analysis of data from NASA’s Cassini mission found evidence of previously…

Continue Reading

-

3,000-year-old map of the Universe discovered at ancient Mayan site

A vast, ancient structure discovered in Mexico may reveal how early Mayan civilisations understood the world to work. In their new study, archaeologists say that new findings indicate the 3,000-year-old site, known as Aguada Fénix, was a…

Continue Reading

-

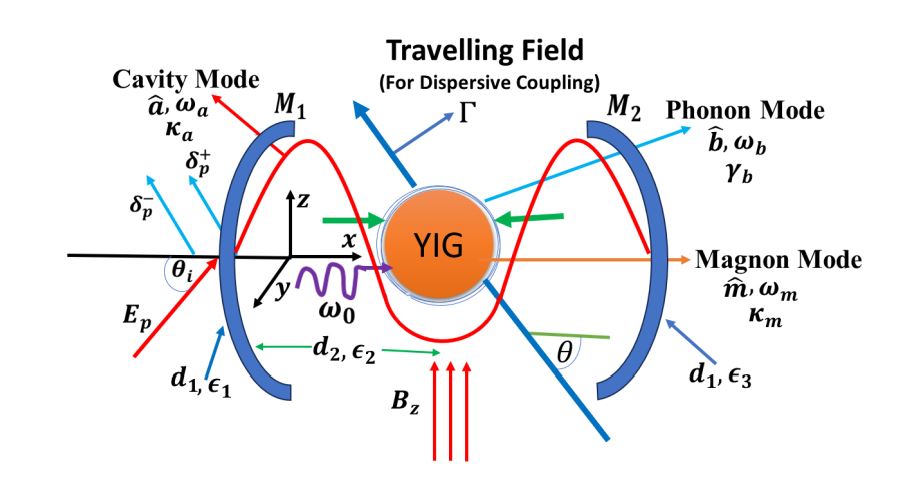

Photonic Spin Hall Effect In Non-Hermitian Cavity Magnomechanics Enables Quantum Transformation And Enhanced Sensing

The interplay between light and magnetism holds promise for advances in quantum technologies, and recent research explores how to control light within unconventional systems. Shah Fahad, Muzamil Shah, and Gao Xianlong, from Zhejiang Normal…

Continue Reading

-

Topological nodal i-wave superconductivity in PtBi2

DFT calculations and BdG model

We performed DFT calculations using the full-potential local orbital code FPLO38 within the generalized gradient approximation39, using the tetrahedron method with 123 points for the Brillouin integration….

Continue Reading

-

Epic Spaceman: Making cosmic scale human

Sarah Al-Ahmed:

Meet Epic Spaceman this week on Planetary Radio.I’m Sarah Al-Ahmed of The Planetary Society with more of the human adventure across our solar system and beyond. When difficult times stifled his career, British filmmaker and…

Continue Reading

-

Scientists make dead nanoparticles emit light with tiny antennas

A long-standing barrier in optoelectronics has been addressed by researchers at the University of Cambridge’s Cavendish Laboratory.

They have invented a molecular “back door” to power materials previously considered useless for modern…

Continue Reading

-

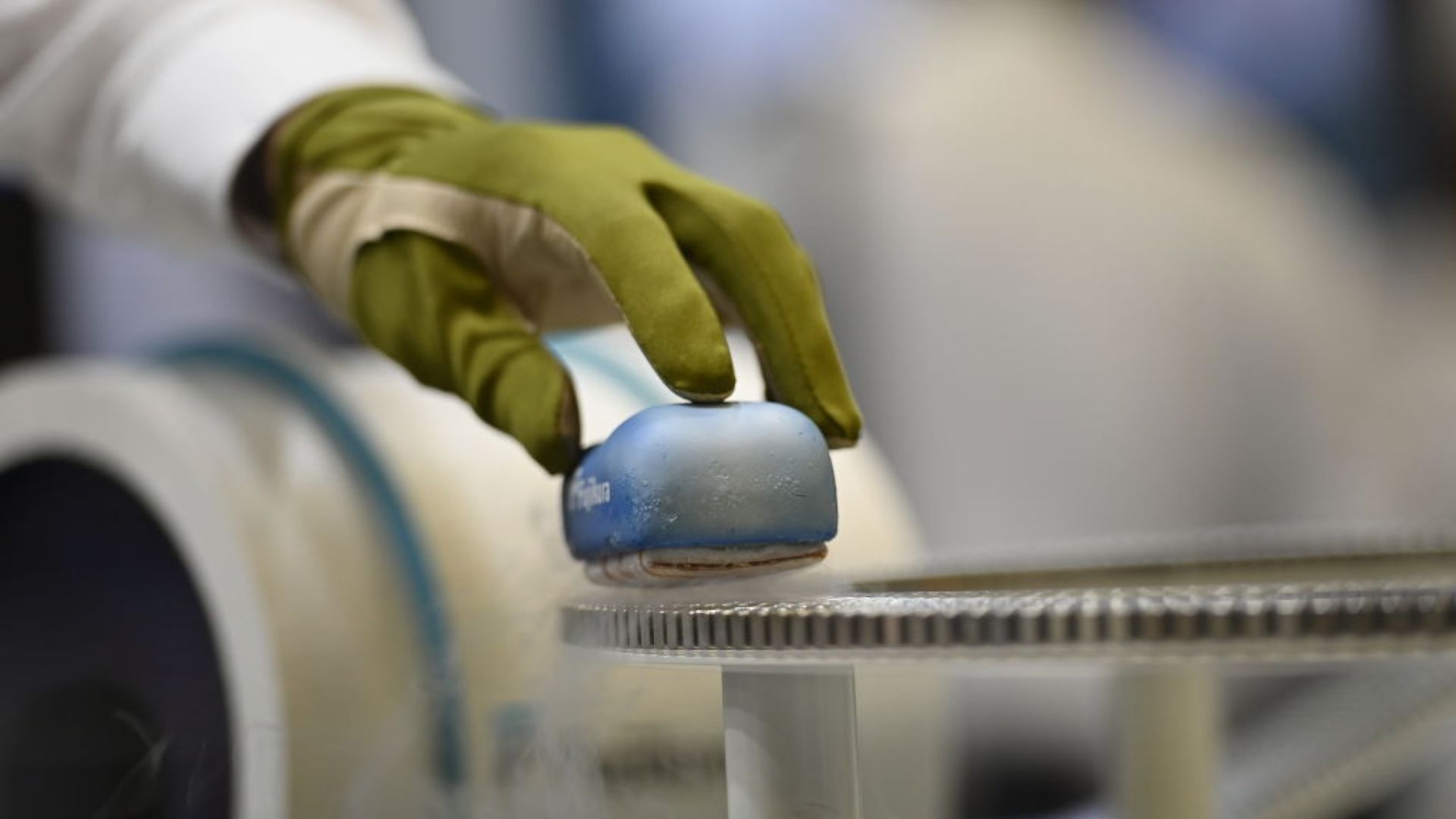

New superconductor shows quantum edge states tied to Majorana physics

Researchers at IFW Dresden and the Cluster of Excellence ct.qmat announced on November 19 that they had identified a new form of superconductivity in the crystalline material PtBi₂. This form displayed a topological behavior and an…

Continue Reading