After three decades of discovering exoplanets, astronomers are turning to a harder question: which of those distant worlds might truly be capable of supporting life? NASA has taken an early step toward…

Category: 7. Science

-

Scientists solve 66 million-year-old mystery of how Earth’s greenhouse age ended

A 66 million-year-old mystery behind how our planet transformed

from a tropical greenhouse to the ice-capped world of today has

been unravelled by scientists, Azernews reports

citing EurekAlert.Their new study has…

Continue Reading

-

Starfish Control Hundreds of Feet Without a Brain. Here’s How. : ScienceAlert

Starfish (aka sea stars) are master climbers. These many-armed invertebrates traverse vertical, horizontal, and even upside-down surfaces: it seems no substrate is too rocky, slimy, sandy, or glassy. And they do so without a centralized…

Continue Reading

-

Scientists Intrigued by Unfamiliar Life Form

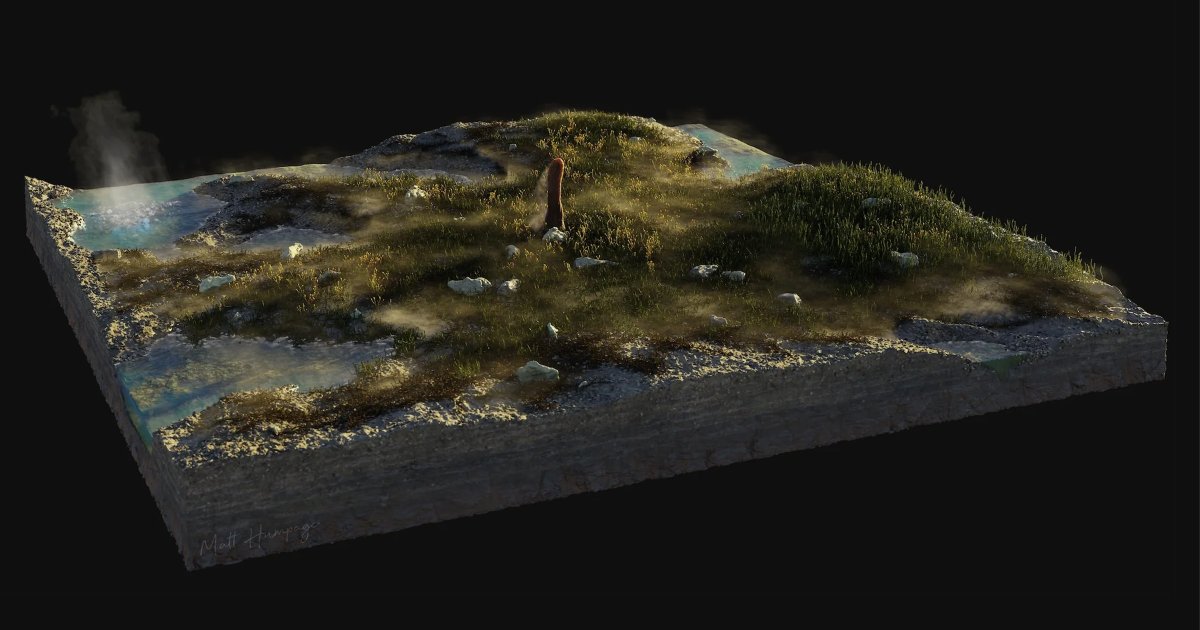

Matt Humpage, Northern Rogue Studios via Loron / Cooper et al. It’s a plant! It’s a fungus! It’s… an entirely new type of lifeform hitherto unknown to science?

That appears to be the case for a…

Continue Reading

-

NASA scientist discovers what Star of Bethlehem likely was 2,000 years later

A new scientific study has attempted to explain what the Star of Bethlehem actually was.

The Star of Bethlehem is referred to as the biblical ‘Christmas star’ from the Gospel of Matthew that guided the Magi (Wise Men) to the birthplace of Jesus.

Continue Reading

-

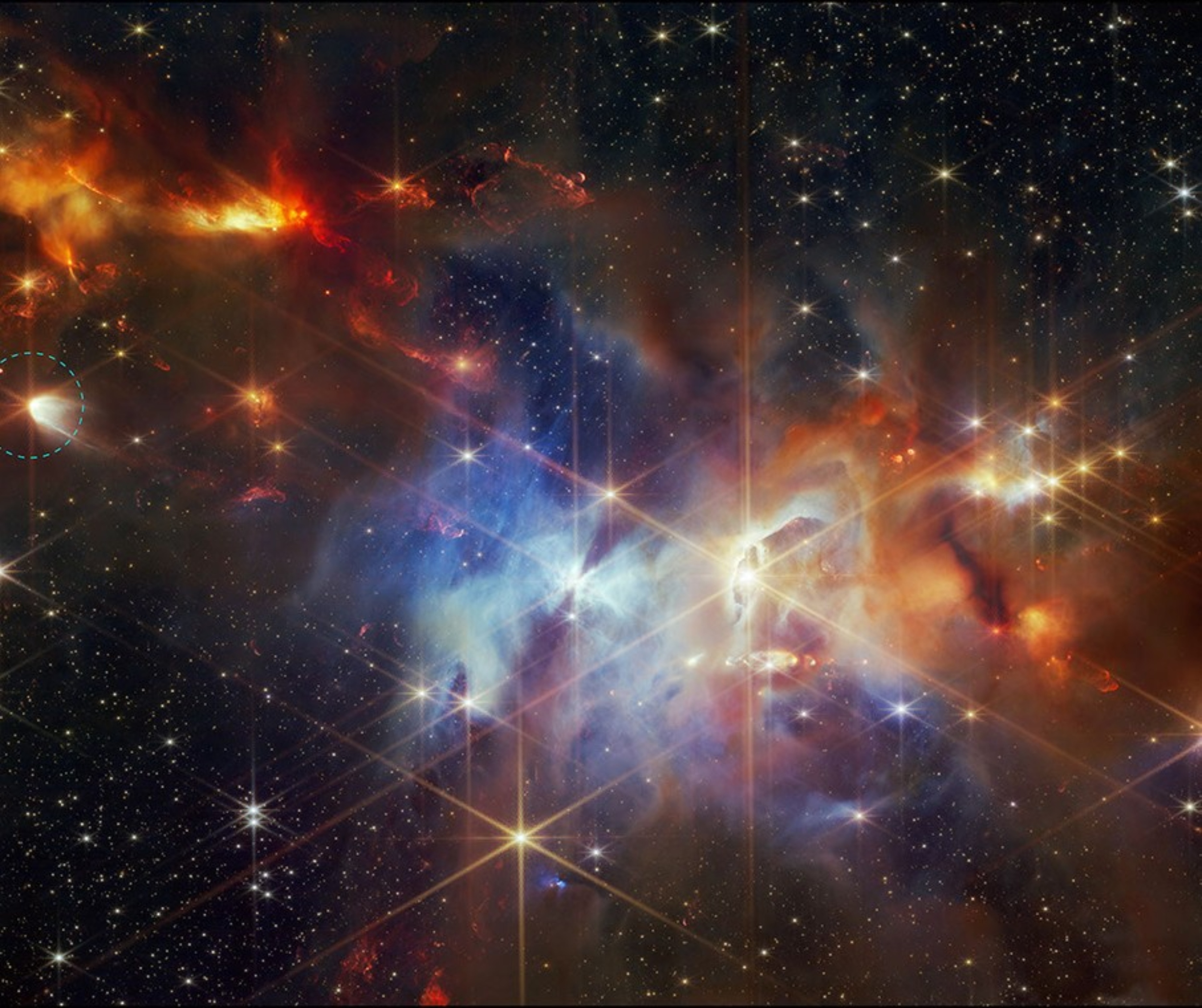

Webb reveals a young star making crystals

Comets have a reputation for being cold, dirty snowballs lingering far from the Sun. Yet for years, astronomers have puzzled over one strange fact.

Many comets contain crystalline silicates – minerals that form only under intense heat. That…

Continue Reading

-

New DNA analysis rewrites the story of the Beachy Head Woman

A long-standing mystery surrounding a Roman-era skeleton discovered in southern England may finally be close to an answer.

Earlier studies suggested the young woman, known as the Beachy Head Woman, may have had recent ancestry from sub-Saharan…

Continue Reading