NASA’s independent Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel (ASAP) has released its 2025 annual report, warning that the agency’s most significant risks stem not from a single program but from interconnected pressures across workforce capability,…

Category: 7. Science

-

Identifying the core catalyst for muscle energy production

Researchers have investigated the role of a certain enzyme in regulating energy in muscle and exercise performance for decades, but a new study by Virginia Tech scientists has identified more precisely than ever how this mechanism…

Continue Reading

-

‘An important and useful tool’

Photos of Earth taken from outer space usually show the beautiful blue and green planet against a field of black — perhaps its most idyllic setting.

In contrast, scientists at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena are zeroing in on a…

Continue Reading

-

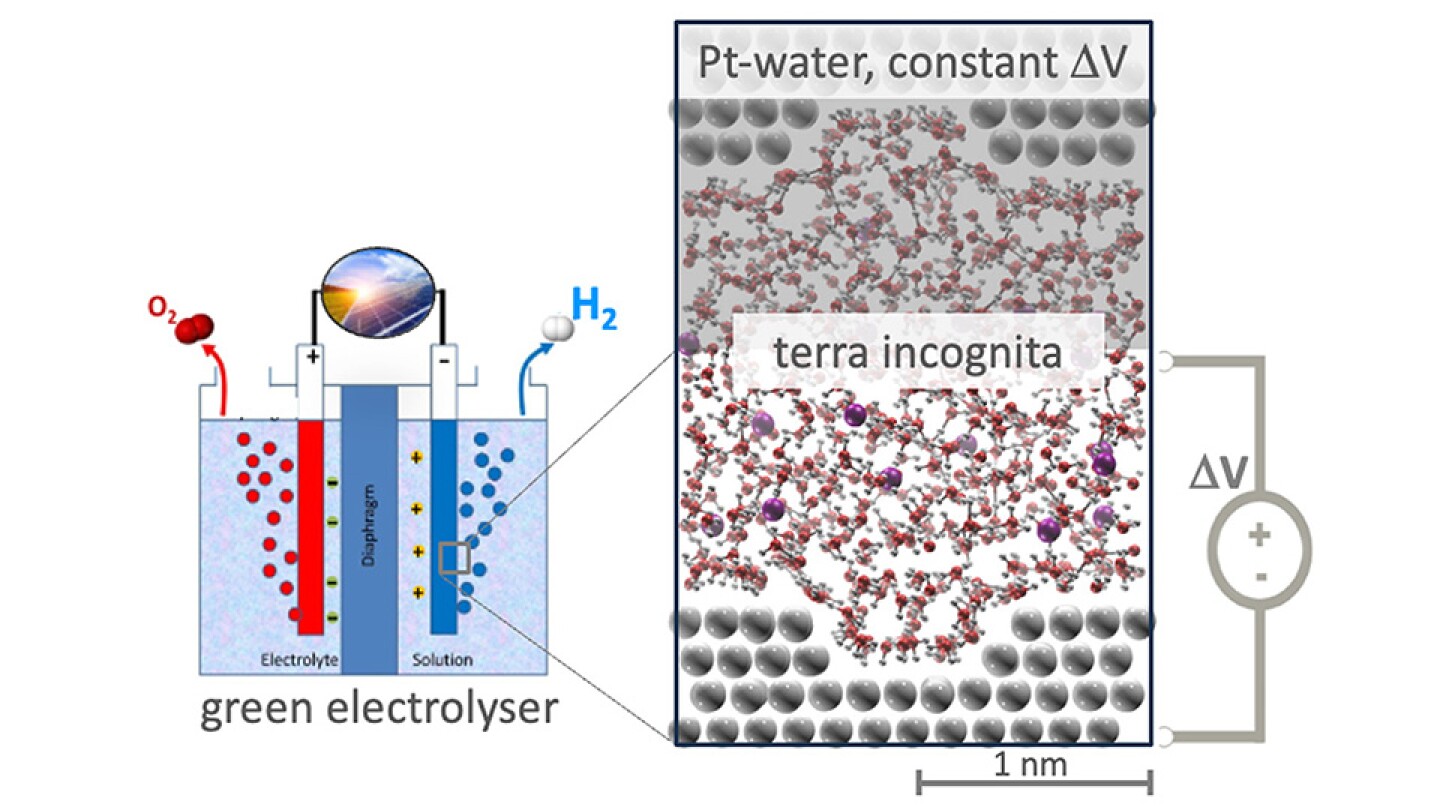

Exploring the role of surface morphology in electrocatalytic interfaces

Nanoscale surface structure at the platinum-water interface has an important effect on electrical properties.

Many chemical reactions,…

Continue Reading

-

Watch SpaceX Dragon cargo capsule head for home today after historic ISS-boosting mission

NASA’s SpaceX 33rd Commercial Resupply Services Undocking – YouTube

Watch OnA SpaceX Dragon cargo capsule will undock from the International Space Station today (Feb. 26), and you can watch its departure live.

Continue Reading

-

Why Does This Galaxy Have Tentacles? Deep Space Mystery Stuns Astronomers – SciTechDaily

- Why Does This Galaxy Have Tentacles? Deep Space Mystery Stuns Astronomers SciTechDaily

- Another Early Universe Surprise From The JWST: A Jellyfish Galaxy Universe Today

- James Webb Space Telescope spots a stunning ‘cosmic jellyfish’ that could help…

Continue Reading

-

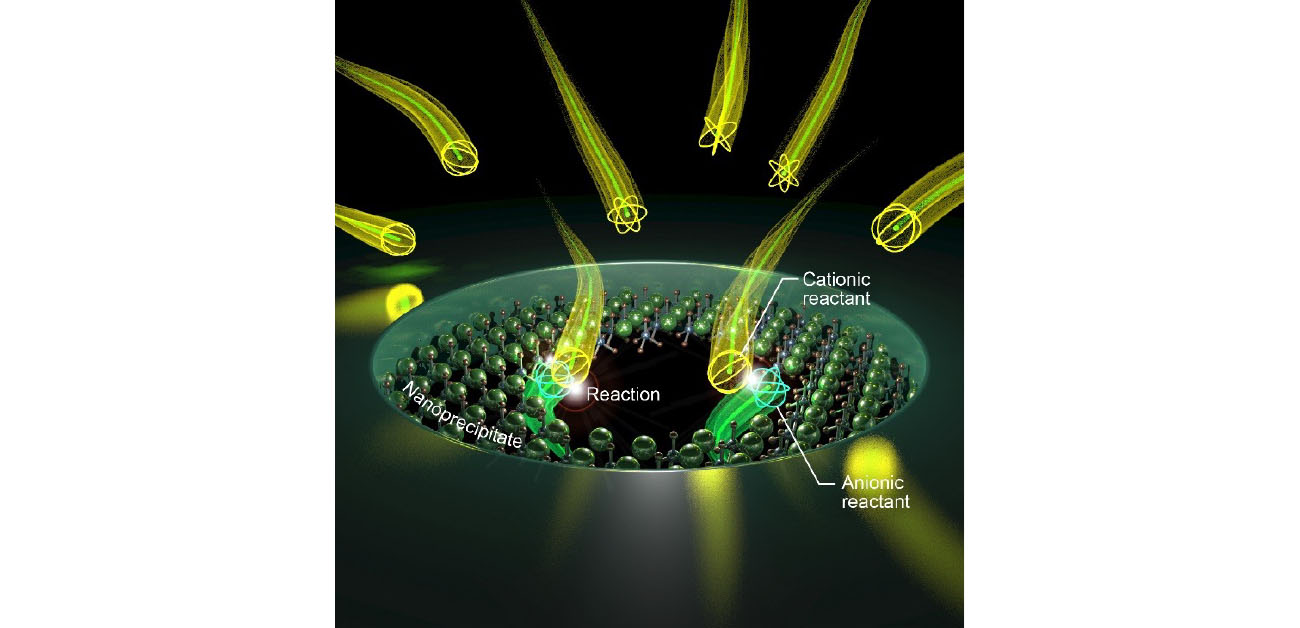

Quick as a blink: Chinese scientists unveil 3D printing in under a second

Chinese scientists have developed a new technique that solidifies liquid into three-dimensional objects in under a second, making for the world’s fastest 3D printing.3D printing is no longer a novel concept – whether it is tech enthusiasts…

Continue Reading

-

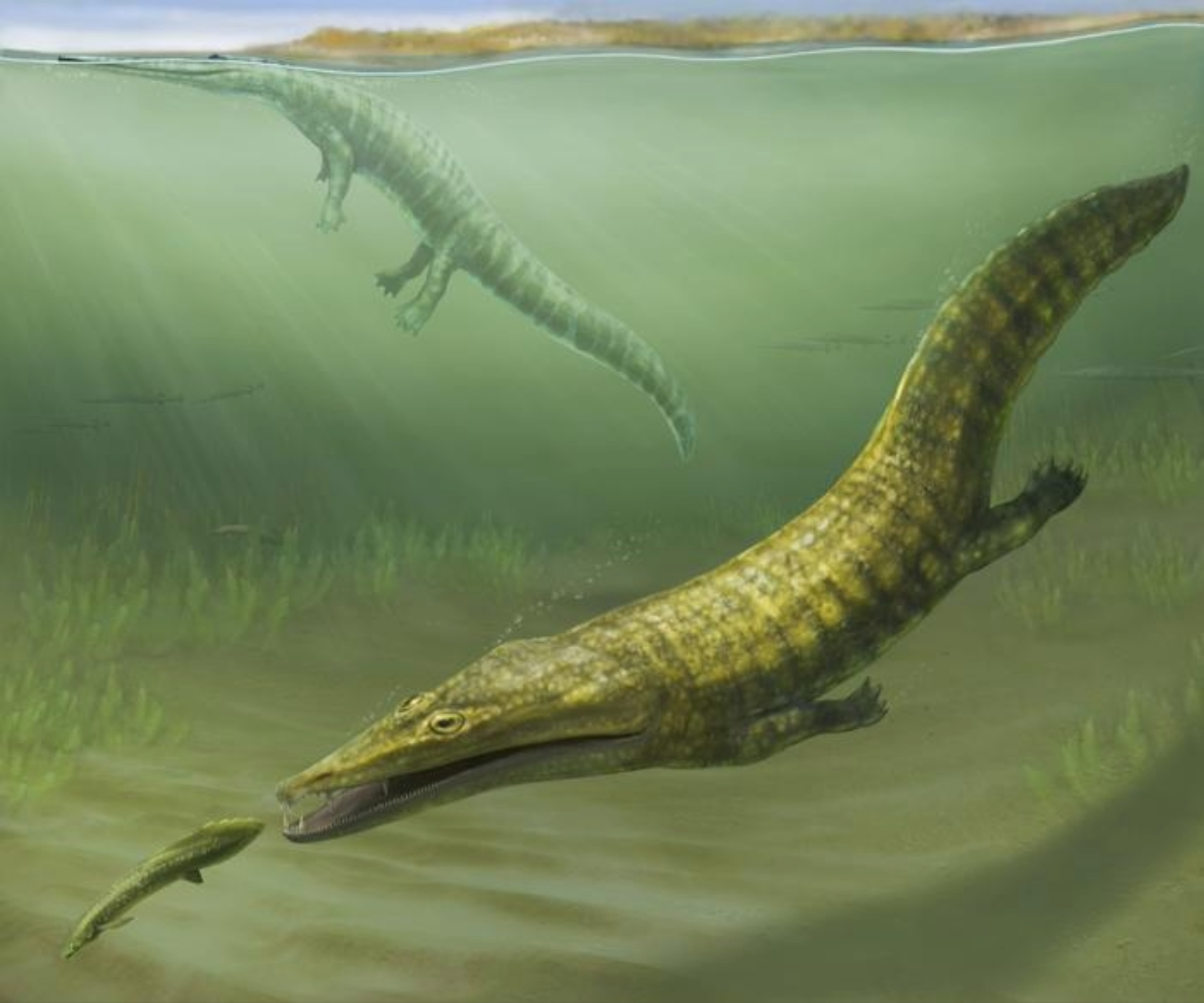

Lost ‘sea monster’ fossils reveal global ocean takeover

Fossils found in northwestern Australia show that 250 million years ago, the red, dusty Kimberley region was nothing like it is today. Instead of a desert, it was a shallow coastal bay, with tropical waters lapping over the area and…

Continue Reading

-

Self-Actuating Membrane Opens, Closes Pores

Ion channels are narrow passageways that play a pivotal role in many biological processes. To model how ions move through these tight spaces, pores need to be fabricated at very small length scales. The narrowest regions of ion channels can be…

Continue Reading

-

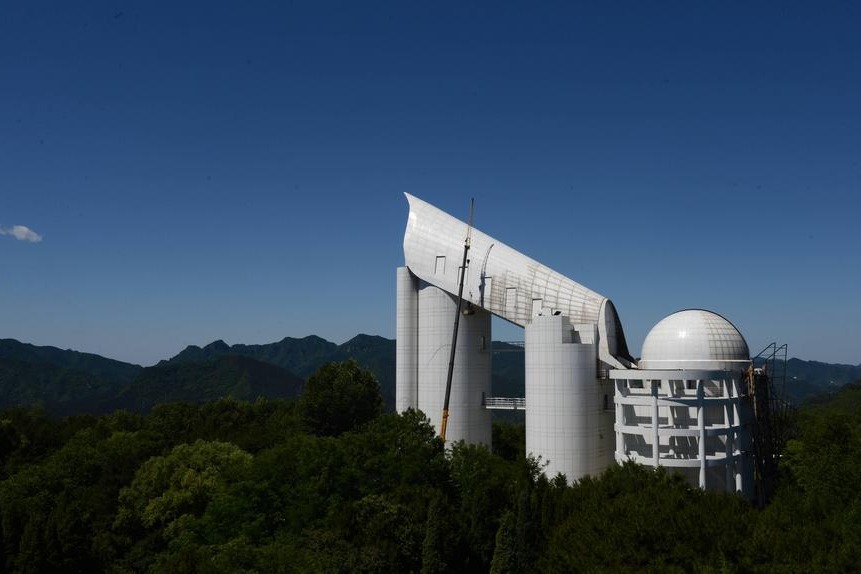

Chinese researchers develop AI model to process stellar data from different telescopes

Photo taken on June 19, 2015 shows the Large Sky Area Multi-Object Fibre Spectroscopy Telescope (LAMOST) at the Xinglong observation station of the National Astronomical Observatories under the Chinese Academy… Continue Reading