BD Helps Scientists Advance Immunology and Cancer Research with AI-Powered Insights and Automation

Newest version of BD® Research Cloud features an AI-powered tool for automated panel design to improve quality, efficiency and usability of scientific results across research areas

FRANKLIN LAKES, N.J., Jan. 23, 2026 /PRNewswire/ — BD (Becton, Dickinson and Company) (NYSE: BDX), a leading global medical technology company, today announced the global commercial release of BD® Research Cloud 7.0, furthering the company’s AI roadmap while strengthening its leadership in flow cytometry and life sciences research. The new release introduces BD Horizon™ Panel Maker, an AI-powered tool for automated panel design – one of the most critical steps across immunology and cancer research experiments designed to help ensure the quality and usability of scientific results.

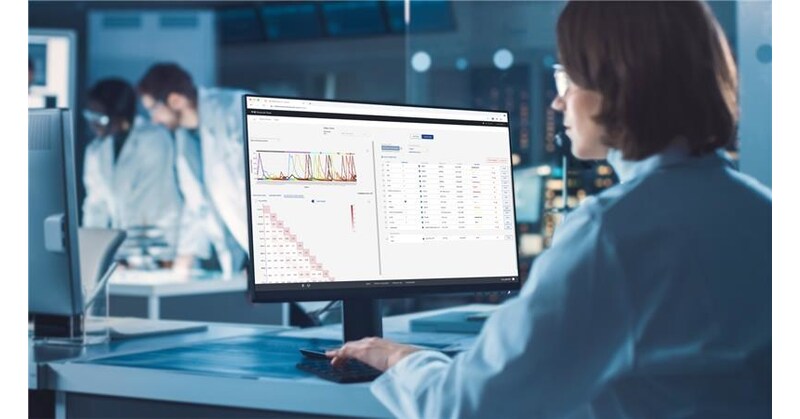

BD® Research Cloud version 7.0 provides scientists with a cloud-based ecosystem for flow cytometry that supports collaboration between team members, streamlines workflows, and manages laboratory operations, from instrument health to purchasing and managing reagents.

The new BD Horizon™ Panel Maker tool leverages a novel, sophisticated AI algorithm to generate optimized panel recommendations within seconds. Researchers can create panels using custom experimental inputs or draw from curated databases of validated options. Poorly designed panels can lead to unusable, unreliable or irreproducible data, resulting in wasted time, samples, and reagents. By providing automated recommendations and integrated visualization tools, like comparison tables and complexity scores, BD Horizon™ Panel Maker enables researchers to more efficiently evaluate and select the panels best suited for their experiments.

“By harnessing the power of AI, the new version of BD® Research Cloud is engineered to help scientists reach high-quality scientific insights in a fraction of the time, while reducing complexity and potential for error,” said Steve Conly, worldwide president, BD Biosciences. “This new AI tool also unlocks the full potential of our BD FACSDiscover™ Cell Analyzer and Cell Sorters, letting researchers get the most out of both cutting-edge hardware and software, for even the most complex experiments.”

BD Horizon™ Panel Maker is the only commercially available tool that supports integrated imaging and spectral panel design when working with BD FACSDiscover™ Instruments.

BD® Research Cloud version 7.0 with BD Horizon™ Panel Maker is now available at bdresearchcloud.com. More information is available at bdbiosciences.com.

About BD

BD is one of the largest global medical technology companies in the world and is advancing the world of health by improving medical discovery, diagnostics and the delivery of care. The company supports the heroes on the frontlines of health care by developing innovative technology, services and solutions that help advance both clinical therapy for patients and clinical process for health care providers. BD and its more than 70,000 employees have a passion and commitment to help enhance the safety and efficiency of clinicians’ care delivery process, enable laboratory scientists to accurately detect disease and advance researchers’ capabilities to develop the next generation of diagnostics and therapeutics. BD has a presence in virtually every country and partners with organizations around the world to address some of the most challenging global health issues. By working in close collaboration with customers, BD can help enhance outcomes, lower costs, increase efficiencies, improve safety and expand access to health care. For more information on BD, please visit bd.com or connect with us on LinkedIn at www.linkedin.com/company/bd1/, X (formerly Twitter) @BDandCo or Instagram @becton_dickinson.

|

Contacts: |

|

|

Media: |

Investors: |

|

Fallon McLoughlin |

Adam Reiffe |

|

Director, Public Relations |

VP, Investor Relations |

|

201.258.0361 |

201.847.6927 |

|

fallon.mcloughlin@bd.com |

adam.reiffe@bd.com |

SOURCE BD (Becton, Dickinson and Company)