With a new study in the journal Science Bulletin, researchers at Sun Yat-Sen Memorial Hospital, Sun Yat-Sen University have discovered a new way that aggressive breast cancer cells escape the immune defenses. This discovery also…

Category: 6. Health

-

Soft wireless bioelectronic implant targets the splenic nerve to reduce inflammation

For millions suffering from chronic inflammatory diseases like inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), managing flare-ups often involves powerful drugs with significant side effects. A new study published in National Science Review…

Continue Reading

-

Label-free polarized light reveals subtle red blood cell deformations

Red blood cells are essential for oxygen transport and immune function in the human body. When these cells become abnormally shaped, they can indicate serious health conditions, including diabetes, malaria, hereditary blood…

Continue Reading

-

Gaming, Videos Don’t Cause Inattentiveness. Social Media Does.

Published: January 1, 2026

Photo from Laura Chouette via Unsplash By Michaela Gordoni

A new study found that social media is causing kids’ attention to drop.

Researchers at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden and the Oregon Health & Science…

Continue Reading

-

Dietitians Pick the Best Low-Sugar Canned Mocktails

- Mocktails are a great alcohol-free option, but many are high in added sugar.

- Dietitians picked their 7 top canned mocktails that taste great and have 5 grams of sugar or less.

- Many options also include mood-boosting ingredients, like lion’s mane…

Continue Reading

-

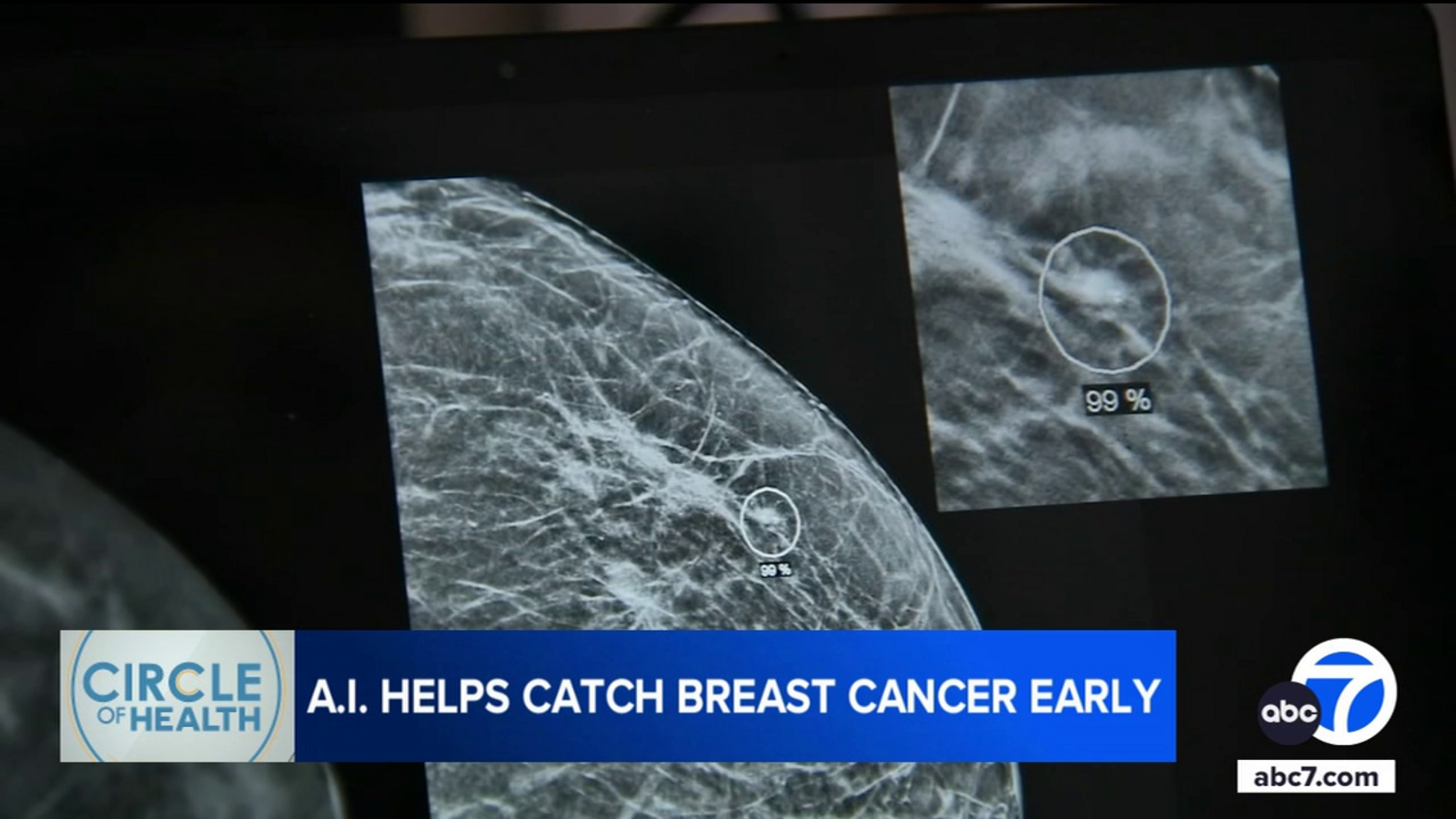

Radiologists at Providence St. Joseph Hospital in Orange County use AI to detect breast cancer earlier

ORANGE, Calif. (KABC) — If radiologists can catch a breast tumor when it’s two centimeters or less, doctors say the cure rate is 90 percent.

Providence St. Joseph Hospital in Orange is pairing artificial intelligence with human expertise to give…

Continue Reading

-

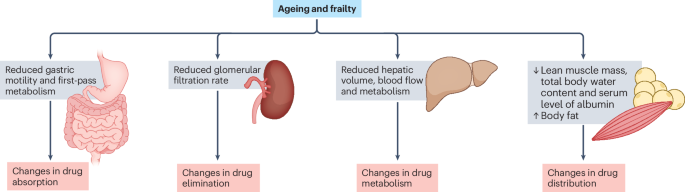

Optimizing cardiovascular pharmacotherapy in older adults with frailty

Heuberger, R. A. The frailty syndrome: a comprehensive review. J. Nutr. Gerontol. Geriatrics 30, 315–368 (2011).

Google Scholar

Clegg, A., Young, J., Iliffe, S., Rikkert, M. O. & Rockwood, K….

Continue Reading

-

Relapsed rhabdoid tumours and other non-nephroblastoma childhood and adolescent kidney tumours: perspectives from the HARMONICA collaboration

Green, D. M. et al. Treatment of Wilms tumor relapsing after initial treatment with vincristine and actinomycin D: a report from the National Wilms Tumor Study Group. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 48, 493–499 (2007).

…

Continue Reading

-

HIV-1 subtype diversity in the pathogenesis of neuroHIV

Keng, L. D., Winston, A. & Sabin, C. A. The global burden of cognitive impairment in people with HIV. AIDS 37, 61–70 (2023).

Google Scholar

Saylor, D. et al. HIV-associated…

Continue Reading

-

Why you don’t need electrolytes for everyday exercise

Getty Images

Getty ImagesElectrolyte drinks have become a staple on gym floors and running routes, promoted as essential for better performance and faster recovery.

Long used by elite athletes to cope with hard training in hot conditions, they have now…

Continue Reading