For people with advanced vision loss, losing the ability to read is often one of the hardest changes to accept. Everyday tasks – such as checking a phone number, reading a label, or recognizing a short word – can suddenly become…

Category: 6. Health

-

Atmospheric CO2 Getting So High That It’s Weakening Human Skeletons

Though talks of climate change typically conjure up images of dripping glaciers and rising tides, it turns out the rapid destruction of our planet is also affecting our bodies in profound ways.

According to new research published in the journal…

Continue Reading

-

Is teen anger linked to faster aging? Here’s what the study reveals

According to a new study published in the journal Health Psychology,…

Continue Reading

-

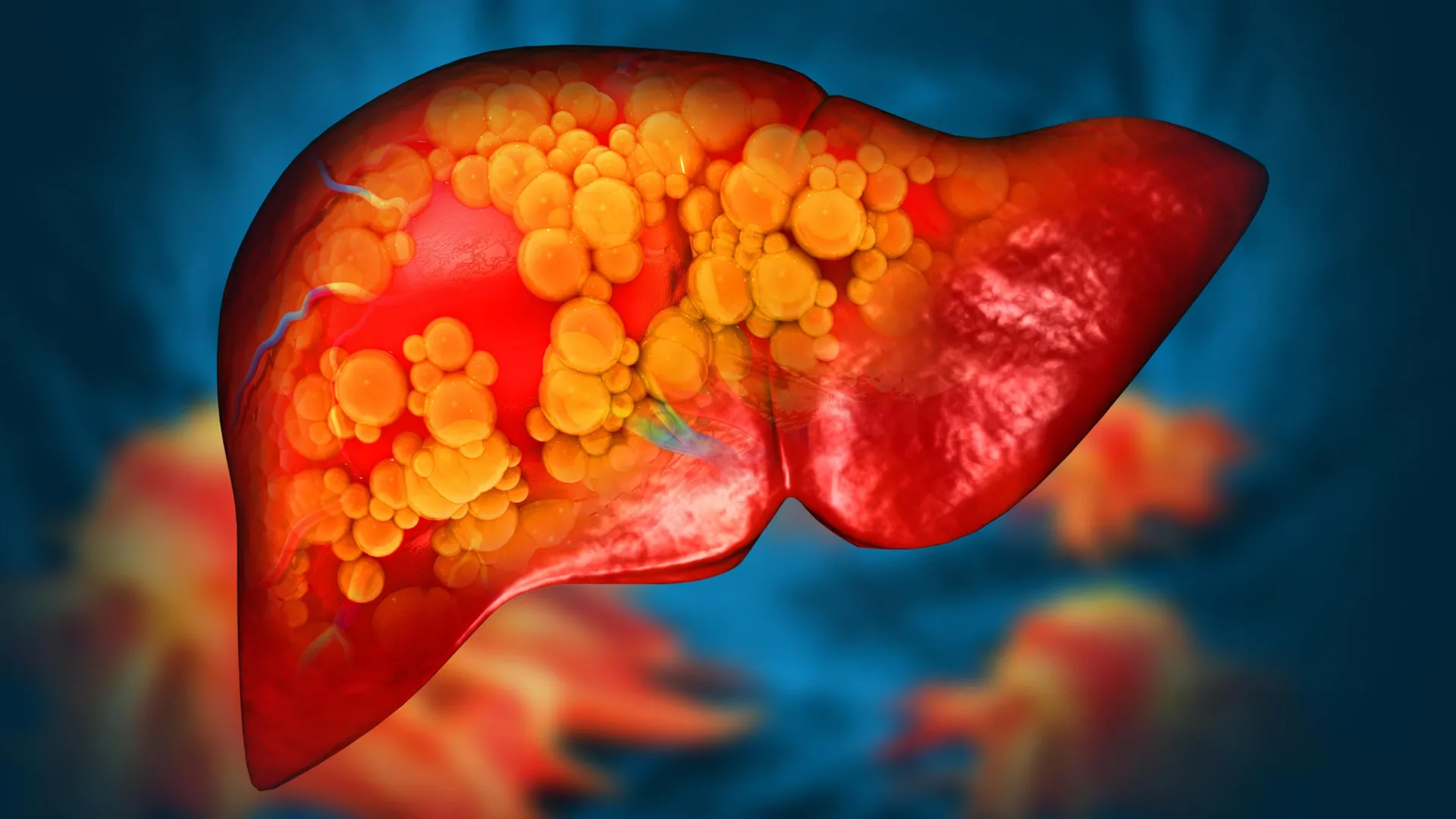

Mayo Clinic discovers rare gene mutation that causes fatty liver disease

Scientists at Mayo Clinic’s Center for Individualized Medicine have identified a rare genetic variant that can directly cause metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease, formerly known as nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

Continue Reading

Scientists discover protein that triggers diabetic blindness

Researchers led by scientists at UCL have discovered a protein that appears to set off diabetic retinopathy, a common eye disease caused by high blood sugar damaging the retina’s blood vessels. The condition is one of the leading causes of vision…

Continue Reading

5 new polio cases reported in S. Afghanistan in 2025: WHO-Xinhua

KABUL, March 7 (Xinhua) — Five new cases of polio were confirmed in southern Afghanistan over the past year, local broadcaster Tolo News reported on Saturday, citing the World Health Organization (WHO).

The cases were identified in…

Continue Reading

Fitness Levels Linked to COVID-19 Hospitalization

Higher cardiorespiratory fitness linked to lower COVID-19 hospitalization risk, but not SARS-CoV-2 infection, in a large population cohort.

Cardiorespiratory Fitness Linked to Lower COVID-19 Hospitalization Risk

CARDIORESPIRATORY FITNESS is…

Continue Reading

China’s top health official urges cancer prevention: early screening and healthy lifestyles key

China”s top health official has called for greater public vigilance on cancer prevention, urging citizens to adopt healthier lifestyles and undergo regular screenings, as early detection remains critical.

Speaking at a…

Continue Reading

Biomimetic smart insole system enables accurate gait monitoring

1. Background:

With the increasing aging population, high incidence of chronic diseases, and the growing number of congenital or acquired foot deformities, lower limb dysfunction and abnormal gait problems are becoming…

Continue Reading

Australia: NSW health minister in damage control after fungal outbreak linked to Sydney hospital deaths

Mounting evidence points to a breakdown in hospital infrastructure and management in New South Wales (NSW), with serious maintenance failures in supposedly hygienic environments now linked to preventable infections, which caused two deaths last…