Crooked teeth or a misaligned bite can cause a whole host of problems, including speech issues and/or difficulty eating or properly cleaning teeth. What many don’t consider, however, is how a bad bite or crowded teeth can affect the…

Category: 6. Health

-

Brazilian study shows increase in Covid-19-era substance abuse-related deaths

The societal and economic impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic included a variety of downstream effects on health endpoints worldwide. Among them, one widely recorded phenomenon was the increase in substance…

Continue Reading

-

Online briefing will cover “From Challenges to Change: HIV & Reproductive Health Insights 2025–2026”

In 2025, faith-based organizations faced unprecedented challenges—from funding uncertainties and policy shifts to humanitarian crises—while striving to uphold health as a human right. These challenges also sparked innovation, new…

Continue Reading

-

Albanian Daily News

Measles cases across Europe and Central Asia declined significantly in 2025 compared to 2024, according to preliminary data reported by 53 countries in the WHO European Region, but the…

Continue Reading

-

New Molecule Blocks Deadliest Brain Cancer at Its Genetic Root – SciTechDaily

- New Molecule Blocks Deadliest Brain Cancer at Its Genetic Root SciTechDaily

- This Deadly Brain Cancer Currently Has No Cure. Scientists Just Found A Way To Kill It IFLScience

- Brown University Health researchers identify new target for glioblastoma…

Continue Reading

-

AI reads brain MRIs in seconds and flags emergencies

A newly developed artificial intelligence system from the University of Michigan can analyze brain MRI scans and deliver a diagnosis in a matter of seconds, according to a new study. The model identified neurological conditions with accuracy…

Continue Reading

-

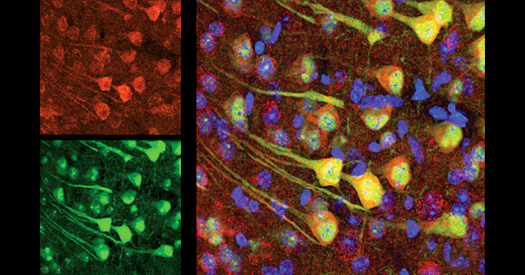

Aging neurons outsource garbage disposal, clog microglia

Synaptic proteins degrade more slowly in aged mice than in younger mice, a new study finds. Microglia appear to unburden the neurons of the excess proteins, but that accumulation may turn toxic, the findings suggest.

To function…

Continue Reading

-

Do men and women face the same mental health challenges? – Deseret News

- Significant differences exist in mental health crisis symptoms for men and women.

- In men and boys, a crisis may be interpreted as simply problem behavior.

- Reducing stigma opens up helpful discussions about mental health.

For years, women died of…

Continue Reading

-

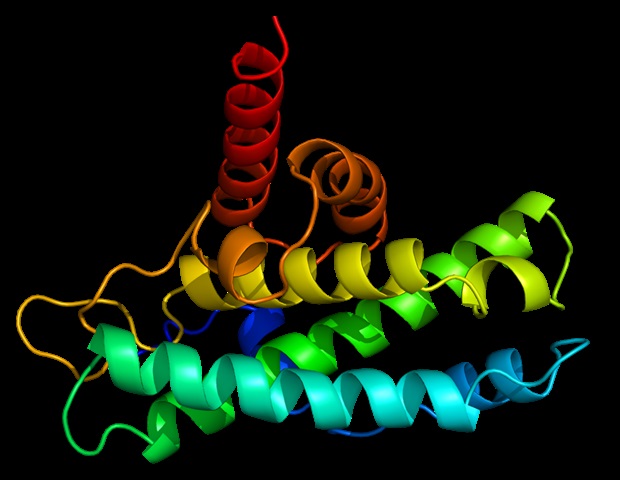

Newly identified protein interaction fine-tunes cellular stress responses

Cornell researchers have discovered a new way cells regulate how they respond to stress, identifying an interaction between two proteins that helps keep a critical cellular recycling system in balance.

The findings show that a…

Continue Reading